Whether you can digest milk comfortably after childhood is a genetic fluke. For many people, the ability to produce lactase–the enzyme that allows the body to break down lactase, the sugar in milk–disappears after childhood, when we no longer need to survive on our mother’s milk.

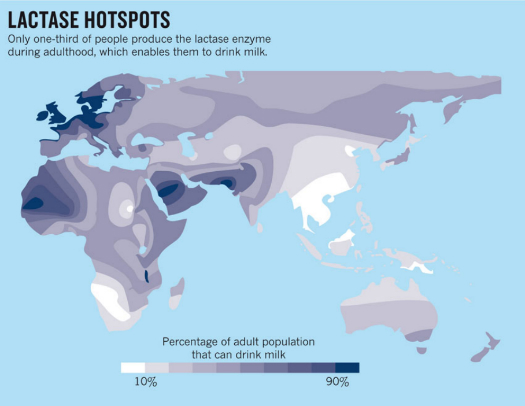

Lactase persistence–the gene that allows about a third of adults to drink milk without major digestive pains–tends to break down geographically, as you can see in this infographic from Nature‘s history of milk tolerance. It’s largely a European phenomenon, evolving from a single genetic mutation that occurred less than 10,000 years ago.

As Nature explains:

During the most recent ice age, milk was essentially a toxin to adults because — unlike children — they could not produce the lactase enzyme required to break down lactose, the main sugar in milk. But as farming started to replace hunting and gathering in the Middle East around 11,000 years ago, cattle herders learned how to reduce lactose in dairy products to tolerable levels by fermenting milk to make cheese or yogurt. Several thousand years later, a genetic mutation spread through Europe that gave people the ability to produce lactase — and drink milk — throughout their lives. That adaptation opened up a rich new source of nutrition that could have sustained communities when harvests failed.

Researchers estimate that the allele for lactase persistence might have popped up as recently as 7,500 years ago, starting in Hungary. The small pockets of milk tolerance in the Middle East, West Africa and southern Asia are thought to be part of different genetic mutations. (The data for this infographic came from a 2012 paper on the evolution of lactase persistence in Europe, which explains why it leaves North and South America out.)

Read more about the history of milk tolerance here.