A copy of the genetic code of an H7N9 avian flu—similar to, but not exactly the same as the flu that has killed 36 people in China—arrived in a lab in Boston Easter Sunday, 2011. By Saturday, scientists had made a vaccine against it, the Boston Globe reported.

That turnaround time is weeks faster than the current best vaccine-making methods. The new shot-making strategy still needs to undergo approval from the U.S. Food and Drug Administration. It also needs tweaking before it would able to make the large amounts of vaccine needed during a flu outbreak, the editors of the journal Science wrote in a summary of the work. If the method does make it to market, however, it could speed the response to flu pandemics.

“I think it does have great potential for more rapidly preparing vaccines for new strains as they evolve,” Robert Finberg, chair of the University of Massachusetts Medical School and a flu researcher, told the Boston Globe.

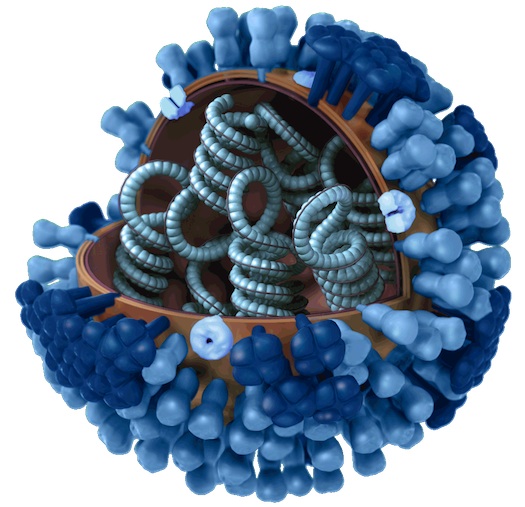

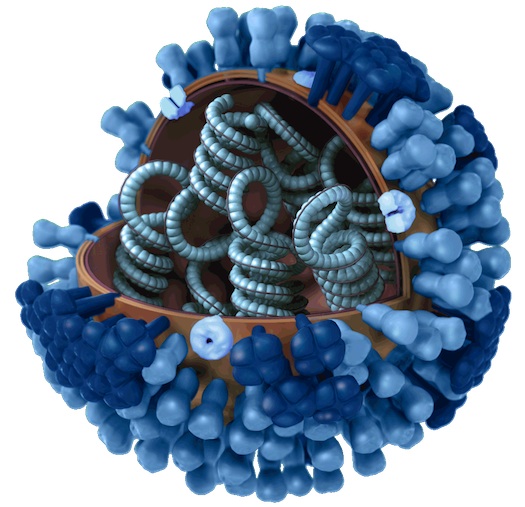

The new method uses synthetic biology, or the creation of biological materials, such as viruses, without using nature’s usual reproductive methods. In this case, scientists from the U.S. pharmaceutical company Novartis and from the J. Craig Venter Institute built H7N9 viruses from looking at the genetic code they received on Easter. Normally, vaccine manufacturers don’t make copies of a flu virus simply from a “paper” (In this case it was electronic, like an email) copy of its code. They actually have to have some virus to make more virus.

It’s as if in the past, scientists always needed to have a burger on hand to make more burgers. The Novartis and J. Craig Venter Institute scientists, on the other hand, looked at a recipe for a burger and made more burgers from individual ingredients. Scientists around the world have previously used synthetic biology to engineer bacteria. J. Craig Venter, namesake of the institute involved in making the new vaccine, made a bacterium almost entirely from scratch in 2010.

Once they had their synthetic H7N9, scientists made a vaccine from a benign form of the virus that stimulates the human immune system, but can’t give people the actual flu. They also came up with some other innovations helped them speed the vaccine-making process. The Boston Globe has more details.

Making the original virus synthetically helps with speed because it’s much faster to send electronic copies of a virus’ code around the world than it is to carefully ship samples of the actual virus, MIT Technology Review reported.

The biggest bottleneck now is performing the tests that will convince regulatory agencies that this method makes safe, effective vaccines, the Science editors wrote. Science published a paper about the synthetic vaccine last week.