When we look at how evolution has taken us from eyeless blobs to moderately capable bloggers, it can seem like a vast, unknowable force. But when we look at individual traits and how they appear and disappear in clever ways, the functioning of cause and effect is clear, and fascinating, to see. People keep poisoning your lake? Well, Mr. Fish, why don’t you develop a resistance to that poison, and pass it down to your kids? Bats keep ignoring your flower and pollinating others? Well, tropical vine, how about evolving an echolocation-reflecting satellite-dish-shaped leaf? We gathered a list of ten evolutions and adaptations that are either new or newly discovered, ranging from plants to animals to, yes, people. We’re not perfect, either.

Click to launch a list of ten amazing evolutions.

A note: these examples span a few different types of changes, including individual mutations (as with the humans), learned behaviors (as with the Muscovite dogs), new adaptations (as with the cave fish) and newly discovered evolutions (as with the satellite-dish-shaped leaf). Think of this as more of an overview of how things can change rather than any particular argument.

Babiana ringens, a South African flowering plant locally known as the Rat’s Tail, shows a very particular evolution to invite pollinating birds to dip their beaks into its flowers: a specialized bird perch. B. ringens‘s flowers grow on the ground, which could mean it garners less attention from birds that don’t wish to hang around in that dangerous spot for too long. To entice the Malachite sunbird, the plant has evolved to grow a firm stalk in a perfect perching position for feeding. This one is interesting because the very same plant shows a distinct difference depending on where it is, according to University of Toronto researchers–when it relies on the sunbird for pollination, it grows a long and appealing stalk (quiet, guys), while in areas with lots of potential pollinators, that stalk has shrunk over many generations of less use. But the stalk is still a major advantage for the plant–plants without the stalk, whether it was broken off or whatever, produce only half as many seeds as those with an intact stalk.

Earlier this summer, we stumbled upon this newly-poison-resistant house mouse, which can now survive some of mankind’s deadliest rodenticide thanks to some very recent hybridization-as-evolution. Warfarin, a common mouse poison, works on most species of mouse, including the common house mouse, but it doesn’t work on the Algerian mouse, a separate though closely related species found on the Mediterranean coast. The two mouse species would never normally have met, but human travel introduced them, and the inevitable hybrid mouse began popping up in Germany, safe and sound–due to this new beneficial trait.

We’re not the only ones who love bats–turns out the Cuban rainforest vine Marcgravia evenia works pretty hard to get their attention, too. In a recently discovered (though not recently developed) evolution, M. evenia‘s leaves have a distinct concave shape that work like little satellite dishes. Why? To send back a strong signal when bombarded with echolocation from bats. That makes the flower uniquely recognizable to our flying mammal friends, who often rely on echolocation to make up for their poor eyesight. The design isn’t great for photosynthesis, but apparently the benefits outweigh the negatives.

The most feared and panic-causing insect in New York isn’t the cockroach–it’s the bedbug. In the late 1990s, after a half-century of “relative inactivity,” as we noted back in May, the bedbug suddenly reappeared, stronger than ever. Turns out the bedbug had evolved in ways that make it much harder to eradicate, including a thick, waxlike exoskeleton that repels pesticides, a faster metabolism to create more of the bedbug’s natural chemical defenses, and dominant mutations to block search-and-destroy pyrethroids. You almost have to admire the little monsters.

A few weeks ago, we found an example of evolution in action: evolution at the cellular level, and within humans to boot. A small study of cardiologists, who use x-rays very frequently in their work, found that the doctors did have higher-than-normal levels of hydrogen peroxide in the blood, a development that could serve as a warning signal for potential carcinogens down the road. But they also found that that raised level of hydrogen peroxide triggered production of an antioxidant called glutathione, a protector of cells. Essentially, these doctors are developing protections against the hazards of their jobs from the inside out, starting deep down inside the cells. It’s an amazing story–read more about it here.

Moscow has a serious stray dog problem. For every 300 Muscovites (we might have guessed “Moswegian” for the demonym, but nope), there’s one stray dog, enough that a researcher at the A.N. Severtsov Institute of Ecology and Evolution, Andrei Poyarkov, has been analyzing them from an evolutionary perspective. Poyarkov has separated the dogs into four personality types, ranging from a reversion to wolf-like qualities to a specialized “beggar” type. That latter type is particular interesting, as it’s a totally new set a behaviors: beggar dogs understand which humans are most likely to give them food, and have even evolved the ability to ride the subway, incorporating multiple stops into their territory. You can read more about Moscow’s dogs here.

The tale of Australia’s cane toads is tragic and mysterious in equal measure. Introduced in 1935 to control the native cane beetle, which was gnawing up the country’s crops, the toads pretty much immediately began breeding like Mogwai and eating up everything in sight, dooming many indigenous species. While the toads spread over most of northeast Australia, researchers began noting something very strange: the toads were mutating to have a very particular set of characteristics: longer legs, greater endurance, more speed. Those mutations allowed the newly evolved cane toads to move faster and spread further, but here’s the thing: it actually made them less healthy. The faster toads had the highest mortality rates, and often developed spinal problems. So what was the point of that evolution? After analyzing the environment, researchers came up with a new term for this kind of natural selection: spacial sorting. The idea is that the faster a toad could move, thus expanding the cane toad’s territory, the easier time it would have attracting a mate–even though the toads were less healthy, and even though there was no real need to keep expanding (certainly not a lack of food). The researchers describe it as “not as important as Darwinian processes but nonetheless capable of shaping biological diversity by a process so-far largely neglected.” [Wired]

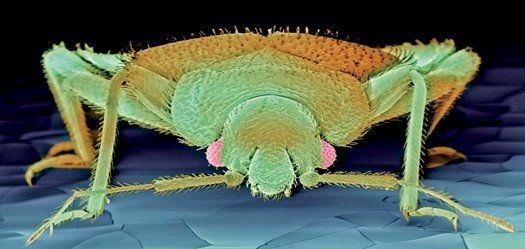

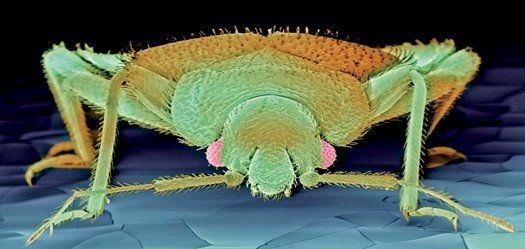

It’s a pretty bad sign when you develop a genetically modified type of corn, weathering all the usual complaints about safety and playing God and all that, all to avoid having your crop gnawed on by a certain kind of pesky bug, only to find that, well, the bug has mutated. That happened to Monsanto (the GM corn maker) and the western corn rootworm (the bug, pictured above in its adult stage). Rootworms developed a natural resistance to the pesticide inherent in Monsanto’s genetically modified corn very quickly. We wrote: “The corn seed also contains a gene that produces a crystalline protein called Cry3Bb1, which delivers an unpleasant demise to the rootworm (via digestive tract destruction) but otherwise is harmless to other creatures (we think).” But an Iowa State University research paper described an instance of the rootworm developing an effective resistance to that protein, raising concerns that the rootworm is flexible enough to respond to all kinds of genetic protection.

We tend to take it for granted that a dog barks–but in the wild, canines hardly ever do, instead whining or yipping or howling. A few studies have examined why this is, and the current conclusion is that dogs bark, well, for us. That conclusion comes in a bit of a roundabout way: Csaba Molnar’s studies show both that a dog’s bark contains information, and that humans can understand that information. Despite a dog owner’s insistence otherwise, dog owners typically cannot tell their dog’s bark apart from the bark of a different dog of the same breed. But humans can quite easily distinguish “alarm” barks from “play” barks, and spectrum analysis shows that alarm barks tend to be very similar to each other, and very distinct from other types of barks. Evolutionarily speaking, dogs are not very far removed from their wild cousins, perhaps 50,000 years, so Molnar’s theory (and the generally accepted theory, to be fair; check out this great New Yorker piece for more) is that wild dogs and wolves were selectively bred for particular traits, one of which may have been the willingness to bark.

Every year, the Zoque people of southern Mexico dump a toxic paste made from the root of the barbasco plant into their local sulfur cave as part of a religious ceremony, praying for rain. The paste is highly toxic to the Poecilia mexicana a small cave fish closely related to the guppy, which is the point of the ceremony. The fish die, the Zoque eat the fish, and hopefully southern Mexico gets some rain. The Mexican government has actually banned this practice, due to that whole massive slaughter of fish thing, but if they had waited a little while longer, they may not have needed to. P. mexicana has actually begun evolving to resist the toxin, according to a paper published last year in the journal Biology Letters. A team of researchers found that some fish somehow managed to survive the wholesale attack, and that even the ones that succumbed seemed to be surviving longer than that species normally would. They tested the fish found in this cave against fish of the same type found elsewhere, and discovered that the cave fish have selectively bred a resistance to the toxin, surviving around 50 percent longer than the non-cave fish. As a side note, this Livescience article on the subject notes that the fish taste pretty awful.