A lone case of rubella doesn’t typically sound the alarms the way a case of measles does. But when it happens at an auto show with hundreds of thousands of attendees it does. Especially when there are two simultaneous outbreaks of measles occurring on either coast.

Rubella is like measles’ little cousin: it causes the same kind of red rash, but isn’t as harmful, debilitating, or contagious (it’s even called “German measles” or sometimes “three-day measles”). You might wonder, then, why you should be concerned at all with one person who attended the North American International Auto Show in Detroit and later turned out to have rubella. So let us tell you.

You can carry rubella without knowing it

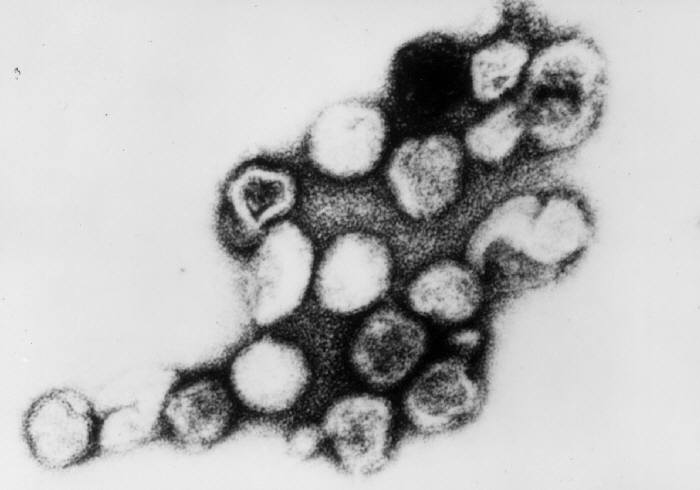

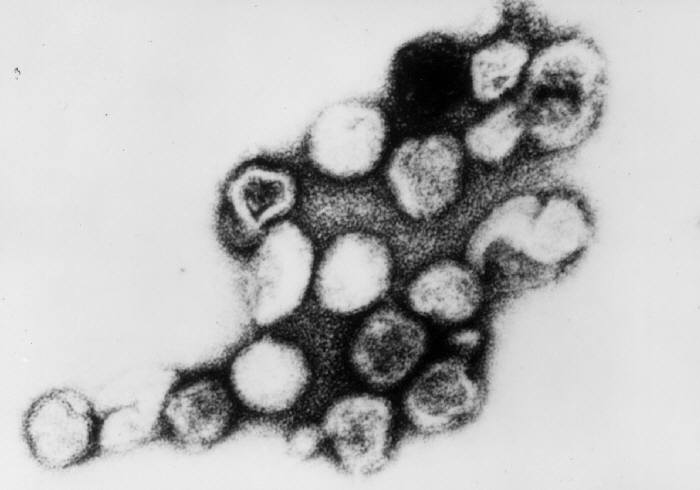

Unlike measles, which can kill children infected with it, rubella is rarely dangerous. Most often they get a rash alongside less common symptoms like a low-grade fever, cough, headache, pink eye, and a runny nose. It’s so generic—even the rash is similar to multiple other illnesses—that the Centers for Disease Control recommends against diagnosing it unless a physician has tested for the virus.

Weirdest of all, anywhere from a quarter to a half of all cases don’t cause any symptoms at all. The rubella virus inhabits the respiratory pathway, and in many people, it just never causes any issues. These individuals are still infectious—they just have no idea they’re spreading the virus. It doesn’t help that you’re contagious for up to a week before and after the rash appears (if it appears at all), so it’s easy to say attend a large event where you might infect a lot of other people without even realizing you’re a risk.

It’s extremely dangerous for pregnant people

Asymptomatic cases are especially problematic for anyone who’s pregnant. Rubella virus can be passed from mother to fetus and cause congenital rubella syndrome, a condition which results in birth defects like heart problems, intellectual disabilities, hearing and eyesight loss, and liver or spleen damage. The mother is much more likely to have a miscarriage if she’s infected early in her pregnancy, or to have a stillbirth. It’s for this reason that women who are planning to get pregnant and haven’t had the MMR (measles, mumps, rubella) vaccine yet get the shot—and why they then wait at least 30 days before trying to get pregnant. Even the rubella virus in the vaccine can cause harm to a developing fetus. That also means that if there’s some kind of outbreak of rubella, a pregnant person can’t get vaccinated to protect herself—she’s just at the mercy of herd immunity, the phenomenon where high rates of vaccinated individuals protect those in the population who can’t be vaccinated from disease.

The U.S. already eliminated rubella

There are very few annual cases of rubella in the states—fewer than 10—and since 2004 all of those have been imported. That is, rubella has no permanent home in the United States, it just enters when someone goes to another country with higher incidence and brings the disease home. Details on the recent case in Michigan haven’t been released, so it’s unclear where that case originated, but in all likelihood it’s someone who traveled internationally. And unless they happen to go to a pocket with very low vaccination rates, they’re unlikely to be able to transmit it much farther.

Vaccination rates are slipping for rubella like they are for measles

Since the vaccine got licensed in the U.S. back in 1969, rubella cases have declined by 99 percent. It’s not as contagious as measles, which means we don’t need as high a threshold to maintain herd immunity. (For measles, we need 95 percent vaccination rates or higher to protect the population from outbreaks, but only 83 to 90 percent to guard against rubella).

But because the rubella vaccine is generally packaged into the MMR shot, rates for rubella immunization are dropping alongside those for measles. It’s just that we pay less attention to rubella because it’s less dangerous.

Like measles, though, we only recently succeeded in eliminating a disease that used to be pervasive. Rubella used to be so common in children that the CDC considers being born before 1957 as sufficient evidence that you’ve been exposed to the virus and are therefore immune to subsequent infection. Now that we’ve come so far, widespread immunity should be easy to maintain—we just have to keep vaccinating our kids.