Before the measles vaccine existed, 9 out of every 10 kids got the disease before age 15. Two million people died from it every year. It’s easy for most of us to forget that, because we’ve had an effective measles vaccine since 1960.

Measles is so infectious that it spreads to 90 percent of those who come in contact with an infected person, though symptoms don’t occur until at least a week later. It starts with the usual: a fever, a cough, a runny nose. A few days later, you develop little white spots inside your mouth. The rash begins soon after. Red dots spread from your hairline all the way down to your feet and your fever spikes, sometimes soaring over 104°F. Most people survive, but if there are complications, death rates can hit up to 30 percent. Pneumonia is the most common fatal side-effect, but patients can also experience swelling of the brain, which can cause permanent deafness or blindness. Prior to the invention of the vaccine, between 15,000 and 60,000 people went blind because of the measles each year.

And yet, despite having a cheap way to prevent one of the most infectious diseases in the world, most countries in Europe still haven’t met the target goal for vaccination coverage. That means those countries continue to have deadly outbreaks.

That’s why the World Health Organization recently warned that measles is making a comeback in Europe, where most had considered it a thing of the past. Europe reached a record-low number of cases in 2016—just 5,273—but saw a spike up to 21,315 last year.

The Sixth Meeting of the European Regional Verification Commission for Measles and Rubella Elimination reported in June 2017 that “progress toward global elimination of measles has slowed” and that “progress towards regional elimination targets is off track.” Less than two out of every three member countries had measles vaccination coverage above 90 percent, and even fewer made it above the recommended 95 percent threshold. Because symptoms don’t appear for a week or so after infection, patients have plenty of time to spread the highly-contagious virus around before doctors know to quarantine them. So to keep a population safe from measles, you need nearly everyone to be vaccinated. Even with most of Europe above the 90 percent mark for more than a decade now, there are still large outbreaks every year.

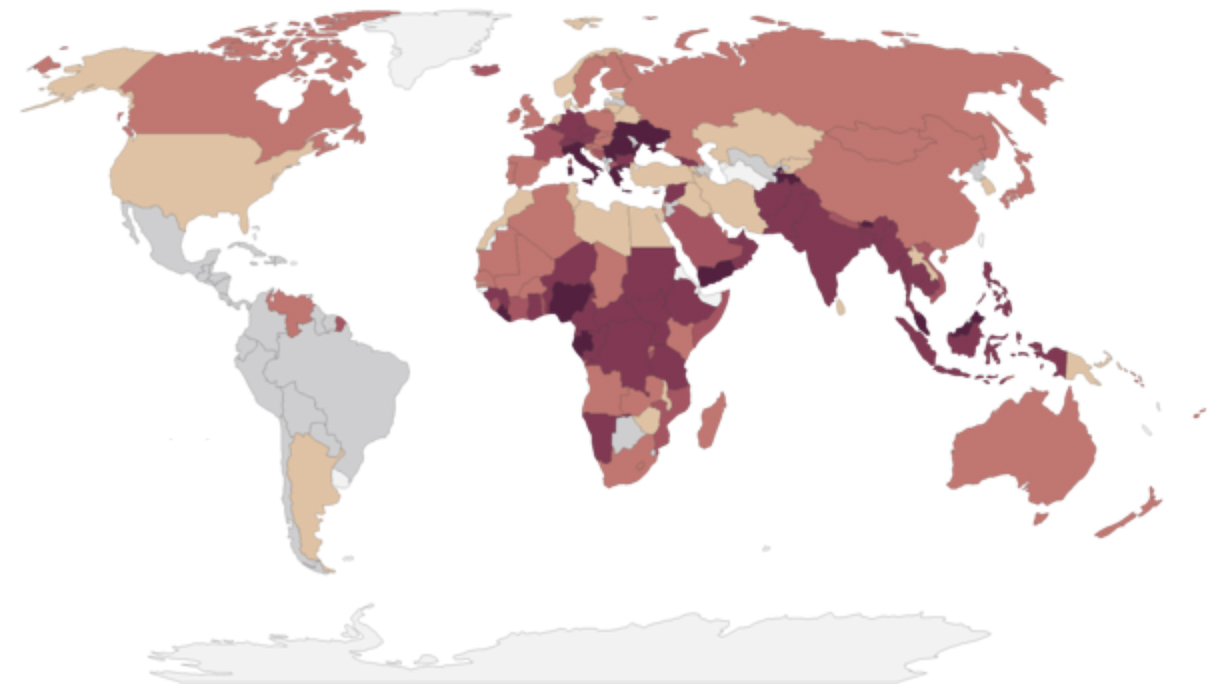

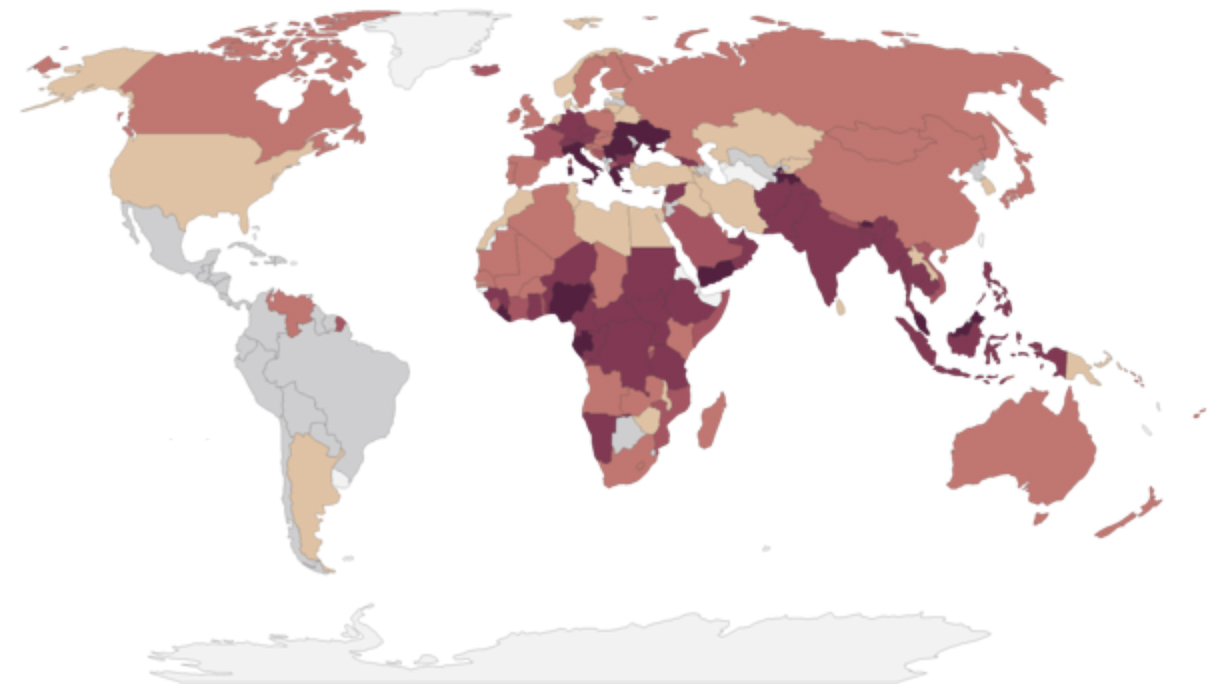

Worldwide, the vaccination rate has plateaued at 85 percent, and that’s due in part to countries stagnating or even slipping on the progress they were making.

Back in 2001, five of the world’s largest health organizations (including the World Health Organization, the United Nations Foundation, and the U.S. Centers for Disease Control) formed the Measles & Rubella Initiative to raise vaccination rates. For the most part, the mission succeeded. Endemic measles was eliminated in the Americas as of September 2016 (meaning cases arise from visitors bringing the virus in, rather than residents being the source of outbreaks). The WHO aimed to achieve the same goal for at least a few other regions, but has so far failed to meet that objective. No other part of the globe has been able to eliminate endemic measles. In fact, the European Regional Verification Commission reported that the global measles case load hasn’t changed much since 2009.

Some countries have actually gone backwards. Romania maintained a vaccination rate over 95 percent from 1997 to 2010, but in 2016 dropped down to 86 percent. Researchers at the University of Oxford wrote last year that the downward trend seems in large part due to anti-vaccination campaigns combined with ineffective efforts to vaccinate rural groups. Romania now has the most measles cases of any European country, and more than most nations worldwide. They are topped only by India, Nigeria, Indonesia, Pakistan, and China.

Italy comes in just under Romania with 5,006 cases in 2017 to Romania’s 5,562. They, too, have seen a drop in vaccination coverage. Italy topped out at 91 percent in 2010, and has since dropped six points. NPR reports the drop of coverage is tied to a rising backlash against mandatory vaccination, and a desire to let parents choose which vaccines to give their children. It took an outbreak among Italian kids in 2016 for the government to require the shot for anyone enrolling in nursery school. We’ll have to wait and see how much of an impact that makes on vaccination rates (and on measles cases) as data comes in over the next few years.

The U.S. is fortunate to have escaped widespread death from the measles in recent history, but we have had outbreaks—and our vaccination rate has hovered around 92 percent for years now. All states technically require students to get vaccinated before attending school, but most also allow exemptions for religious beliefs (and 18 allow exemptions based on personal or moral objections). According to both nationwide and state-specific surveys, more people are getting those exemptions than ever. One 2012 analysis in the New England Journal of Medicine found that exemption rates of all types were increasing by anywhere from 8 to 18 percent a year.

That seems mostly driven by the anti-vaxxer movement, which has flourished since bogus research in the ’90s claimed that the measles, mumps, and rubella vaccine caused autism. It doesn’t, but celebrities and community leaders have used the fraudulent study to convince parents that vaccines are dangerous. Plenty of people who aren’t outright against vaccination still claim exemptions, because they don’t want to take what they perceive as a risk with their child’s health. But in reality, the real risk lies in not vaccinating.

The recent influx of migrants to Europe has plenty of people concerned that these refugees are bringing disease into their countries. It is true that a small number of cases of measles, along with other infectious diseases, have been traced back to immigrants from countries with less robust healthcare. But the rise in measles cases isn’t due to incoming refugees. One 2015 study found that, across 13 European nations, 7.1 percent of all measles cases were due to migrants. Similarly, in the U.S. two separate studies have found that the vast majority of measles cases come from U.S. residents, and that number is only rising. From 2001-2008, 79 percent of cases were from citizens returning from travel abroad, whereas from 2009-2014 it was 93 percent. Most of them were unvaccinated. The WHO’s report agrees: “experience has shown that, when importation occurs, it involves regular travellers, tourists or health care workers rather than refugees or migrants.” They do recommend that countries vaccinate refugees who might be susceptible to certain disease so that any outbreaks that occur in migrant camps will be limited, but they continue to stress that it is vacationing citizens—not refugees—who bring in the majority of these diseases.

The U.K. has a similar problem and an identical vaccination rate, though the nation briefly got to 95 percent in 2015. Oxford researchers warned last year that “Immunisation rates only need to drop slightly below 95% for measles to start circulating more widely in the population, leading to serious illness and deaths.”

It’s so easy to forget what it was like when most children got the measles. Millions of people worldwide feel it’s not a priority to vaccinate their kids, probably in part because they can’t fathom a world where parents regularly lose children to the measles. But such a reality is not improbable, and we are only a couple generations removed from it. Roald Dahl—famous children’s author—lost his own daughter, Olivia, to measles when she was seven and wrote a letter to every parent in 1986:

As the illness took its usual course I can remember reading to her often in bed and not feeling particularly alarmed about it. Then one morning, when she was well on the road to recovery, I was sitting on her bed showing her how to fashion little animals out of colored pipe-cleaners, and when it came to her turn to make one herself, I noticed that her fingers and her mind were not working together and she couldn’t do anything.

“Are you feeling all right?” I asked her.

“I feel all sleepy, ” she said.

In an hour, she was unconscious. In twelve hours she was dead.

It really is almost a crime to allow your child to go un-immunized.

Note: this article has been updated with additional information about infection rates