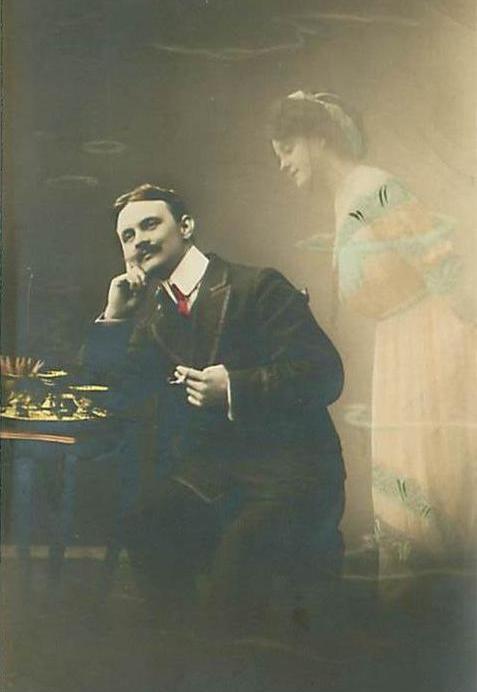

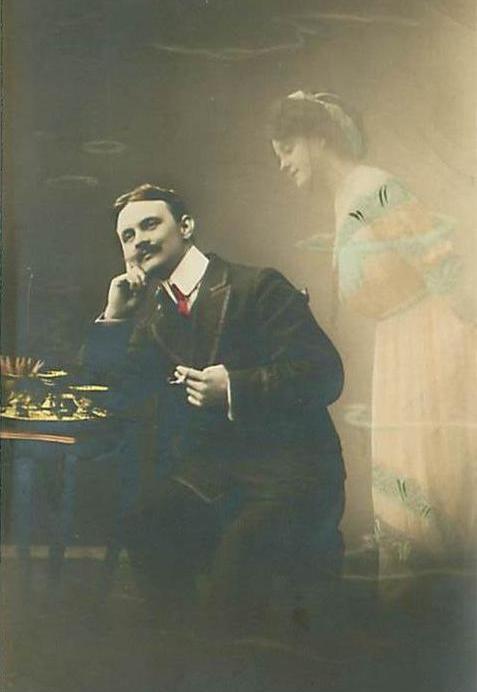

For most people, daydreams are a brief but pleasant escape from reality. And, while it’s tempting to spend entire meetings or lectures in more appealing universes of our own creation, most of us can also rein in our imaginations when we have to.

But some people find it almost impossible to pull out of their daydreams. People with “maladaptive daydreaming” become so immersed in their elaborate fantasies that it becomes difficult to live their daily lives.

Maladaptive daydreaming should be considered a mental health disorder, Eli Somer of the University of Haifa in Israel, who came up with the term, told the Wall Street Journal. In fact, maladaptive daydreamers devote an average of 57 percent of their waking hours to fantasy, Somer and his colleagues reported in a new study in the journal Consciousness and Cognition. On particularly dreamy days, this went up to 69 percent. By comparison, people without the condition spend 16 percent of their time daydreaming.

After surveying 340 self-labeled maladaptive daydreamers recruited from online chat rooms, the scientists found that these people also had more reveries concerning fictional characters and intricate plots than others. They also had high rates of attention deficit and obsessive compulsive symptoms. Nearly all of them felt that their daydreaming interfered with their sleep, chores, relationships or life goals. Many felt as though they had an addiction.

“It stops me from interacting in real world and real people,” one person told the researchers. “I can’t concentrate on studies. I skipped school a lot just to be in my world.”

Another reported having 35 distinct characters in her daydreams. “I cannot remember a time when my mind was alone, with just myself. They have always been there.”

Earlier this year, Somer and his team also created a 14-item scale to gauge extreme daydreaming.

Some experts are resistant to the idea that maladaptive daydreaming should get its own diagnosis. “Once you start psychopathologizing these things you can get yourself in trouble, because often normal mechanisms account for this,” Eric Klinger of the University of Minnesota, Morris, told the Wall Street Journal.

Still, Somer plans to develop ways to diagnose and treat maladaptive daydreaming. “If one is spending an average of 57% of his or her waking hours on under-controlled fantasy activity, it is not surprising that it is also jeopardizing fulfillment of life goals that take time and attention to achieve, underscoring the need learn more about [maladaptive daydreaming] and to find appropriate treatments,” he and his colleagues concluded in the new study.