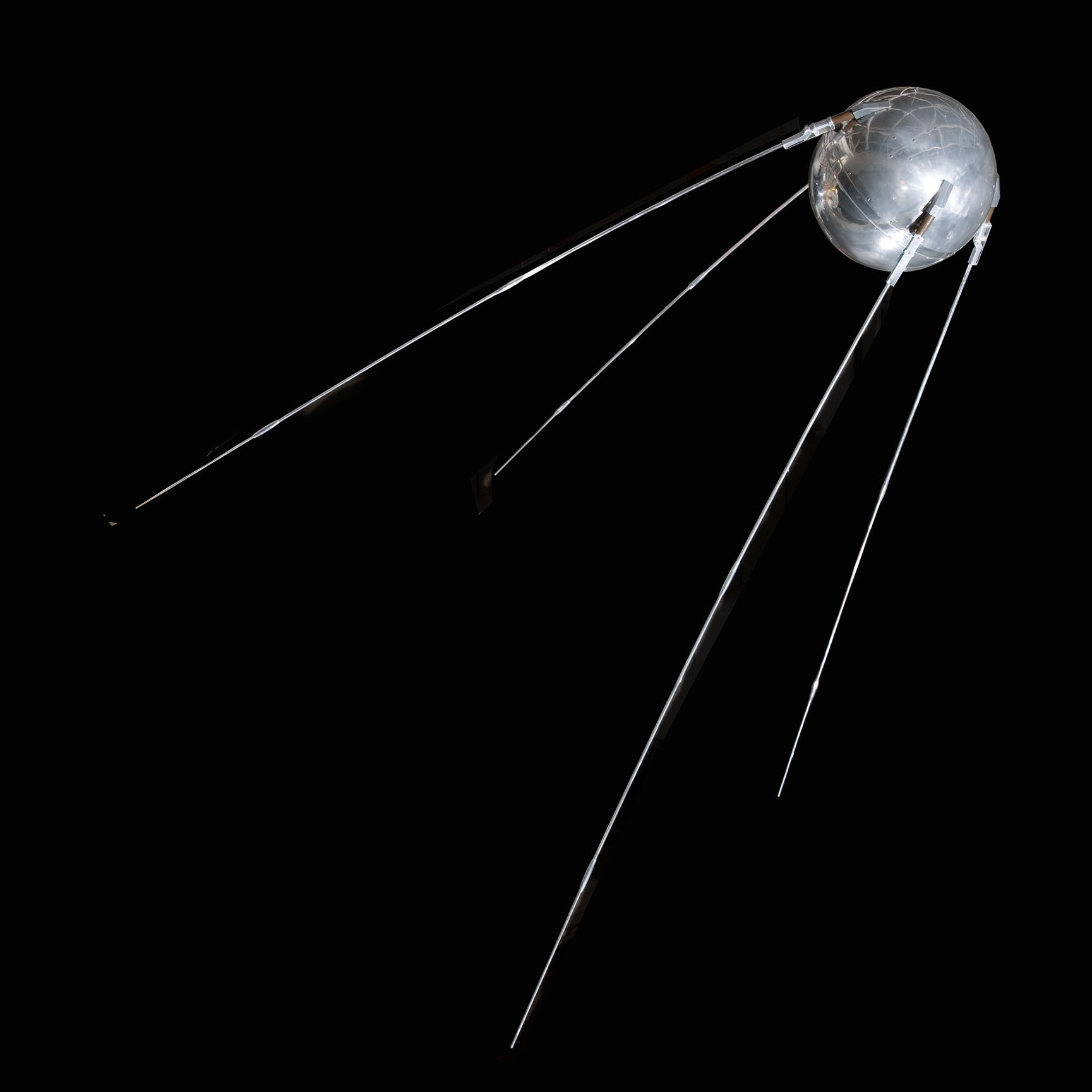

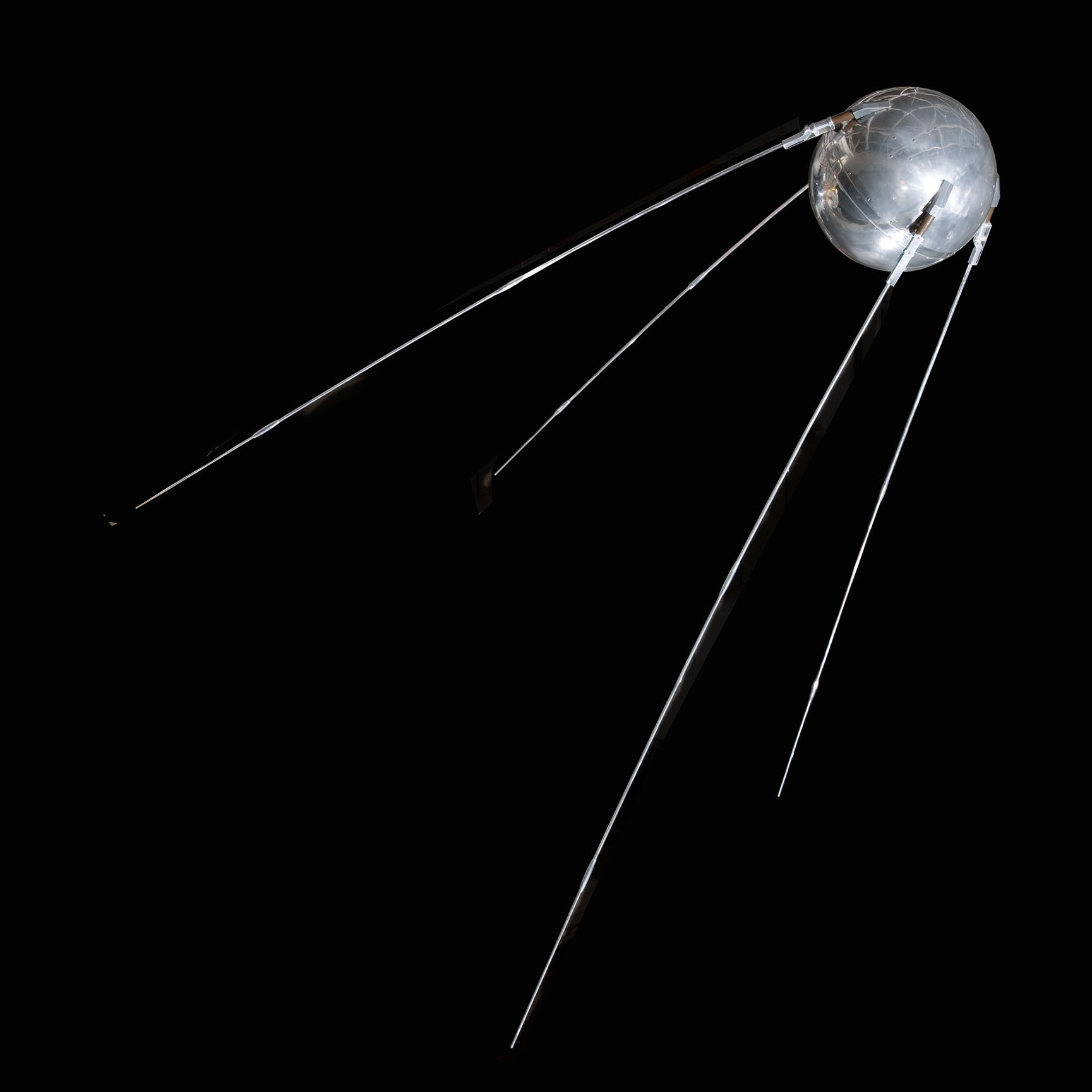

The United States was shocked by Sputnik’s launch on October 4, 1957, but it maybe shouldn’t have been. Just like the United States, the Soviet Union had announced its intention to launch a satellite years earlier under the guise of the International Geophysical Year.

The International Geophysical year was an 18 month period from July 1957 to December 1958 during which international teams of scientists would pool resources to study the Sun during a solar maximum and all related geophysical phenomena. There had been two such international collaborations before. The first International Polar Year between 1881 and 1884 saw some 700 scientists from eleven nations at twenty-seven research stations around the world gather data about the Earth’s poles. Half a century later, a second international cohort braved arctic conditions to establish research stations during what became the Second International Polar Year from 1932 to 1933. But the Second World War disrupted the second polar year, and the gathered research was left untapped until a 1946 Liquidation Commission was formed to tie-up all outstanding issues.

Around the same time, slowly repairing international relations prompted scientists to revisit the idea of a collaborative research program. In September of 1950, the idea of a third Polar Year coincident with an upcoming solar maximum was well received by a number of international research bodies including the International Astronomical Union, the International Council of Scientific Unions, and the World Meteorological Organization, but consensus was the proposal would be with the focus shifted from polar science to geophysical science. The International Council of Scientific Unions created the Committée Speciale pour l’Année Geophysique Internationale — the Special Committee for the International Geophysical Year — in late 1952 to oversee all elements of the upcoming IGY.

By the time the CSAGI held its first meeting in Brussels midway through 1953, more than 30 nations were behind the IGY. The United States’ own contribution started taking shape in the spring of 1954 as one focused on ground-based research stations complemented by upper atmosphere data gathered using suborbital sounding rockets and rockoons. These high altitude payloads would carry instruments to measure atmospheric pressure, temperature, density, and return data about the strength of magnetic fields and the phenomena behind night and day airglow. These rockets would launch from a variety of locations on predetermined “World Days,” days of notable solar activity so the data returned would yield the most fruitful results possible. But as the scope of the IGY got bigger, sounding rockets were tentatively replaces with larger rockets intended to put scientific satellites into orbit.

Meanwhile, the international nature of the IGY meant support went beyond scientific circles into the political arena. In the United States, the American IGY program was managed by the National Science Foundation meaning President Dwight Eisenhower had to sign off on all elements. The President was keen on the program that stood as a unique and striking example of international partnership. He was also found the prospect of launching an IGY satellite since this would make the first space shot a peaceful, scientific endeavour rather than a political move; that the exploration of space be a peaceful undertaking was paramount for Eisenhower.

Once the United States’ committed to an IGY satellite program, the International Council of Scientific Unions urged other participating nations to consider launching satellites as well. The Soviet Union answered the ICSU’s call, and though it wasn’t officially a participating nation in the IGY in 1954 it wasn’t barred from taking part providing it freely exchange all of its gathered data.

The American satellite program was formally approved with an announcement from the White House on July 29, 1955; the program would be co-run by the National Science Foundation and the National Academy of Sciences with technical advice coming from the Department of Defense. International interest followed. Unwilling to be outdone, Soviet delegates at the Sixth Congress of the International Astronautical Federation in Copenhagen in August of 1955 their nation’s intention to launch a satellite during the IGY as well. Few gave credence to the Soviets’ boastful promises that their satellite would not only launch first but would be far more sophisticated than any American attempt.

I tell the story of the IGY and how it let to the first satellite race, not only between the Soviet Union and the United States but between branches of the US military as well, in my book “Breaking the Chains of Gravity.” It’s in stores in the UK now and will be released in the US on January 12. You can (pre)order it on Amazon or buy a signed hardcover copy on my website, though my shipping is slower than Amazon’s! Sources: This article was edited from work that appears in my book, Breaking the Chains of Gravity.