Ghana is the first country to approve a malaria vaccine for young children, who have the highest risk of death from the disease. Some scientists have called the new vaccine a potential “game-changer” in the fight against the disease that is the leading cause of child death in Africa.

This new vaccine, called R21, has an efficacy rate of 77 percent, according to a September review in the journal The Lancet. One approved Malaria vaccine already exists, called Mosquirix, which has a 30 to 60 percent efficacy rate.

Late stage testing is still underway in Burkina Faso, Kenya, Mali, and Tanzania. It’s unusual for a country to approve a vaccine before clinical trials are completed, according to WHO guidelines, and the World Health Organization has yet to approve it.

Oxford researchers shared the mid-stage data with regulatory authorities in Ghana over the past six months and their new data suggests similar performance as in earlier trials, according to Oxford Professor and Chief investigator of the R21/Matrix-M programme, Adrian Hill. The results of R21’s final trials are expected to be published in the coming months.

[Related: New four-dose malaria vaccine is up to 80 percent effective]

Oxford researchers shared the mid-stage data with regulatory authorities in Ghana over the past six months and their new data suggests similar performance as in earlier trials, according to Oxford Professor and Chief investigator of the R21/Matrix-M programme, Adrian Hill. The results of R21’s final trials are expected to be published in the coming months.

The R21 vaccine is designed to stop disease and death, not prevent transmission, although vaccines that prevent transmission between people are currently in the works at Oxford, Hill said in a press interview.

“The main idea now is to get R21 out there as soon as possible, and then add a transmission blocking vaccine,” Hill said. “That will allow us to use vaccination, not just for disease control, but for initial disease elimination, and then eventually global eradication.”

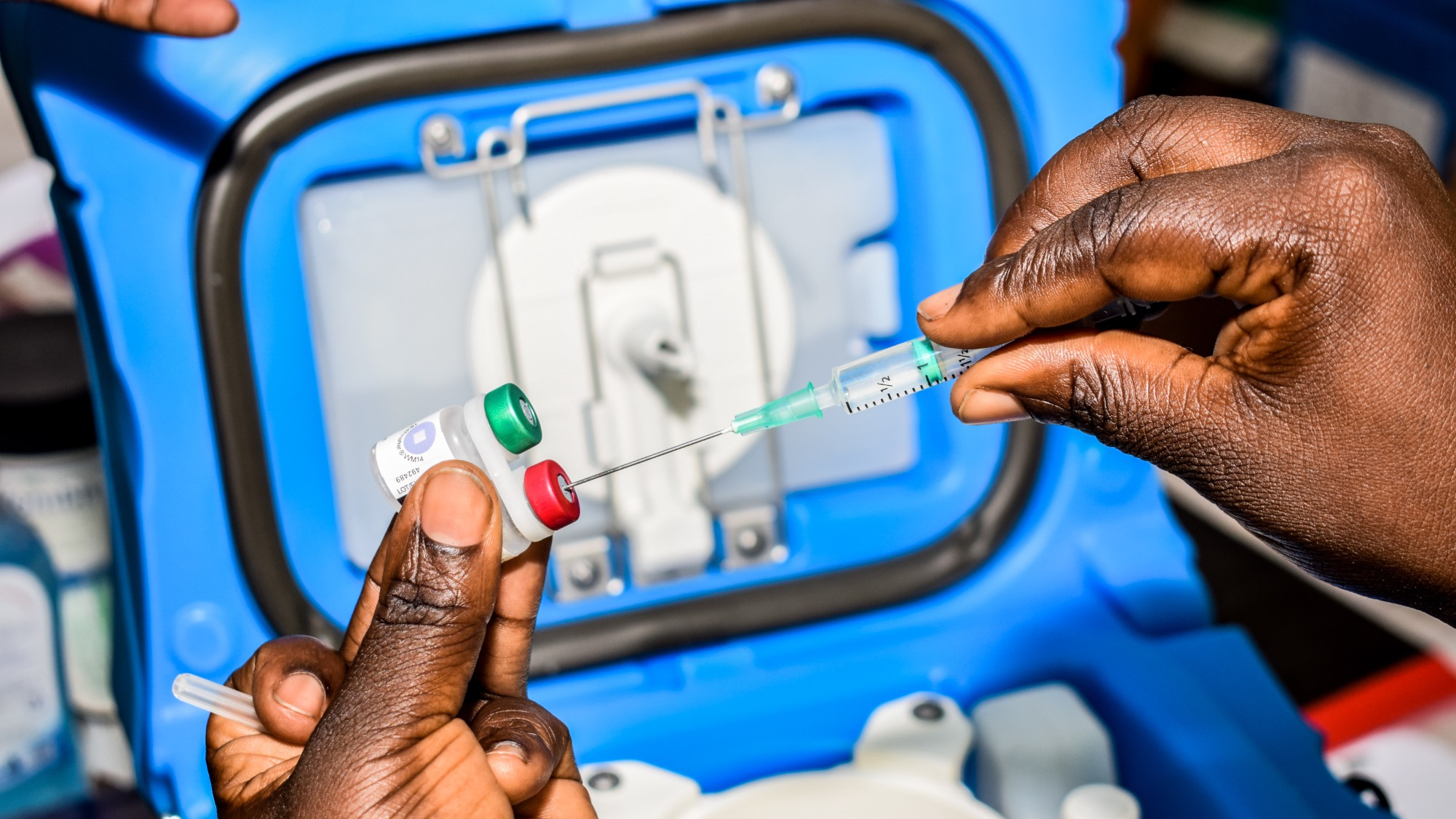

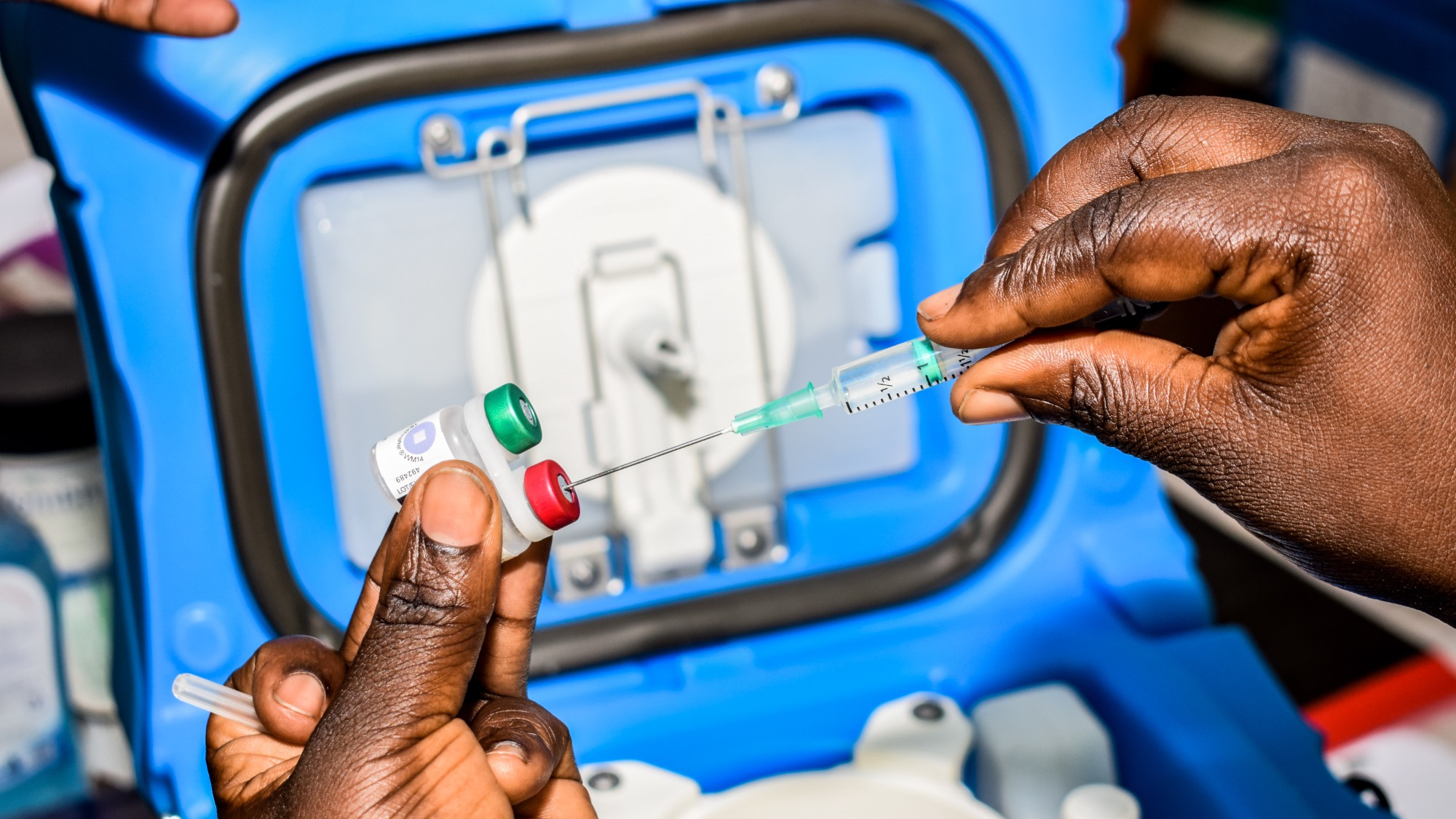

Ghana’s Food and Drug authority approved its use for children aged five months to three years, but rollout will be delayed until the WHO approves it. Once it is approved, Ghana’s drug regulator has a deal with the Serum Institute of India to produce up to 200 million doses of R21 a year. Each dose is expected to cost a couple dollars, per the BBC.

The mosquito-borne disease kills about 620,000 people globally each year, and 77 percent of those deaths are children. That translates to a death toll of over one thousand children each day, nearly one child lost per minute, according to UNICEF.

Malaria is a parasitic disease transmitted by mosquitoes, most often seen in tropical and subtropical climates. It is preventable and curable. Symptoms range from mild to life-threatening, including tissue inflammation in the brain, kidneys, and lungs. In extreme cases, leading to cerebral malaria, kidney failure, and acute respiratory distress syndrome. Children, pregnant women, and immunocompromised individuals are most at risk.

The parasite responsible for Malaria is the unicellular plasmodium. There are multiple plasmodium species known to cause the disease, each with its own unique characteristics. Unfortunately, the most common species in sub-saharan Africa, Plasmodium falciparum, is also the most deadly.

Vaccinations are a relatively recent method of treatment for malaria. Since Mosquirix was introduced in 2019, 1.4 million children across Ghana, Kenya, and Malawi were vaccinated, resulting in a 10 percent drop in child mortality. A lack of funding and commercial potential has prevented drugmakers from producing adequate amounts of Mosquirix.

The release of the R21 vaccine “marks a culmination of 30 years of malaria vaccine research at Oxford with the design and provision of a high efficacy vaccine that can be supplied at adequate scale to the countries who need it most,” Hill said in a statement.

There are multiple reasons why a Malaria vaccine is hard to develop—including the complex life cycles of the parasite and its ability to evade immune responses.

However, the biggest barrier is not biological, it’s financial. Malaria is most prevalent in sub-saharan Africa, making up 95 percent of all malaria cases and 96 percent of malaria deaths. This region is also home to low-income countries, which have limited resources for research funding and vaccine development.

[Related: White House invests $5 billion in new COVID vaccines and treatments as national emergency ends]

“Malaria is a life-threatening disease that disproportionately affects the most vulnerable populations in our society and remains a leading cause of death in childhood,” Adar Poonawalla, CEO of the Serum Institute of India, said in a press release statement.

“We remain steadfast in our commitment to scaling up production of the vaccine to meet the needs of countries with high malaria burden and to support global efforts towards saving lives,” he said.