The Central California coast is proving to be a playground for baby sharks. Earlier this year, we caught a glimpse of what could be the first images of a newborn great white shark. Now, we’re learning more about where they like to live during their formative years. Juvenile great white sharks select warm and shallow waters and congregate about half a mile from shore. These findings are described in a study published April 19 in the journal Frontiers in Marine Science and could have crucial conservation implications.

This water column is too cold

After they’re born, baby great white sharks–called pups–do not get any care from their parents. This new study looked at one of these populations of young sharks off Padaro Beach near Santa Barbara in Central California. Here, pups and juveniles gather together in ‘nurseries’ and are unaccompanied by adults in a sort of shark never, neverland, except these fish will eventually grow up.

“This is one of the largest and most detailed studies of its kind, because around Padaro Beach, large numbers of juveniles share near-shore habitats, we could learn how environmental conditions influence their movements,”study co-author and California State University, Long Beach marine biologist Christopher Lowe said in a statement. “You rarely see great white sharks exhibiting this kind of nursery behavior in other locations.”

[Related: This could be the first newborn great white shark ever captured on camera.]

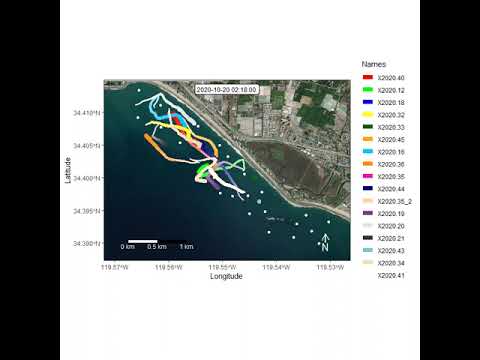

In 2020 and 2021, the team tagged 22 juveniles with sensor-transmitters. Great white sharks can live for up to 40 to 70 years and the younger sharks in this study were all females and males between one and six years old. The sensor-transmitters measured local water pressure and temperature in real time. They also tracked each shark’s position by sending out “pings” to several receivers spread out over roughly two miles along the shoreline.

When the juveniles temporarily left for offshore waters in the winter, the tracking was stopped. The team gathered more information on the temperature distribution with an autonomous underwater vehicle. With this data in hand, they used artificial intelligence to generate a 3D model of the juveniles’ temperature and depth preferences.

The juveniles dived to the greatest depths around dawn and dusk. This is likely when they were foraging for rays, skates, and schooling fish. They moved closer to the surface–between zero and 13 feet deep–during the afternoon when the sun was warmest. This shift towards the warmer water was potentially to increase their body temperature. They directly altered their vertical position within the water column to stay between 60 degrees and 71 degrees Fahrenheit. Their sweet spot also appeared to be between 68 and 71 degrees.

“This may be their optimum to maximize growth efficiency within the nursery,” study co-author and California State University, Long Beach research technician Emily Spurgeon said in a statement.

Keeping to the shallows

The temperature distribution in the water changes quite frequently, which means that the juveniles must constantly be on the move to remain within optimal range. They believe that this is why juvenile great white sharks spend more time in shallow water than adults tend to. Additionally, adult sharks were rarely observed in the nursery.

[Related: With new tags, researchers can track sharks into the inky depths of the ocean’s Twilight Zone.]

According to the team, the results show that the temperature distribution across three dimensions strongly impacted how the juvenile sharks were distributed. They spread out at greater depths when seafloor temperatures were warmer, and moved closer together towards the surface of the water when deeper water was cooler.

However, the team is still not sure what benefits the pups and juveniles have from gathering in nurseries in the first place. It could potentially help them avoid predators like some whales.

“Our results show that water temperature is a key factor that draws juveniles to the studied area,” said Spurgeon. “However, there are many locations across the California coast that share similar environmental conditions, so temperature isn’t the whole story. Future experiments will look at individual relationships, for example to see if some individuals move among nurseries in tandem.”

Great white sharks are considered vulnerable, with their populations decreasing in some parts of the world. Knowing where baby and juvenile sharks like to hang out can help inform better conservation laws to protect them as a species. It can also help protect the public from negative shark encounters.