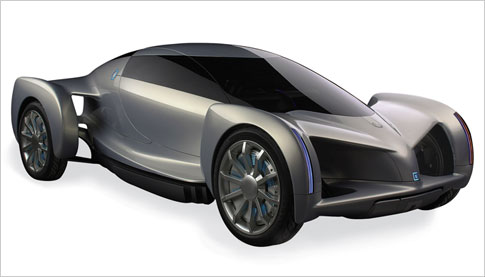

Long, wide and low-slung, the car looks exotic, unplaceable. “It’s the length of a Mercedes CLS, the width of a BMW 7-series, and the height of a Porsche 911,” says the corporate spokesman at the wheel. The front end is so long that it must hold at least a V8, but in fact there is no discernible engine noise, only the quiet whine of electric motors. Instead, a pair of external speakers emits—for effect—a sound somewhere between a Formula One car and a starship.

The car is a racy four-door, with two more roomy seats behind us and trunk enough for two sets of golf clubs. Above us stretches a solar panel, built into the roof. And the whole thing is controlled by a cutting-edge touchscreen in the dash. As we wheel into a fancy shopping center, I feel like James Bond arriving at MI6.

Or at least, that’s what I imagine it’s like to ride in the Fisker Karma. It’s the long-awaited plug-in hybrid supercar that is supposed to usher in a new era of upscale, luxurious green transportation—and hopefully at the same time revive the American automotive industry. Backed by a $529-million U.S. government loan, plus another $300-odd million in venture capital, Fisker Automotive aims to do what Tucker and DeLorean could not: create a new, big, successful American carmaker. “This car is more sexy and exciting than any other car you’ve seen,” boasts designer Henrik Fisker. Maybe it is. But I haven’t driven one.

I’d tried for weeks to snag a rare Karma test drive, but no dice. So right now the flack and I are sitting in his black Audi wagon, with a purple baby seat in the rear. No head-snapping torque, no starship noises, no revolution on wheels. “We’re just not ready to show it yet,” he says as we pull into the mall to pick up lunch.Almost no one outside the company has ever driven the Karma. The lone exception is the Crown Prince of Denmark (well, his chauffeur), who arrived at December’s Copenhagen global-warming summit in one. Apart from car shows and a handful of low-speed public appearances, the seven working prototypes have been off-limits to outsiders. Even now, seven months before working cars are supposed to arrive in Fisker’s 45 dealerships, the company has yet to allow a journalist to ride in a Karma. Even the Fisker sound, meant to alert pedestrians, is under wraps. “We’re not releasing that yet,” the spokesman tells me. “We don’t want to give away the secret sauce.”

THE ROAR OF SILENCE

Perhaps Fisker’s secrecy is strategic. After all, 1,600 paying customers have preordered the $88,000 Karma without even a test drive. His reputation is what does it. Fisker created the BMW Z8 roadster featured in the 1999 Bond film The World Is Not Enough and then, at Aston Martin, updated the beloved Vantage V8. He’s a god of car design. But the secrecy has also fueled skepticism about the company. The Karma’s delivery date has slipped from the fourth quarter of 2009 to September 2010 to “later this year.” Customers placing new orders, meanwhile, supposedly won’t receive a Karma before next spring.

This is supposed to be the year of the electric car, the beginning of the New Age of the automobile. A handful of electric vehicles (EVs) and next-generation hybrids are set to reach the market over the next 12 months.

The theme among most of these cars is practicality. Last month, customers began to reserve the eco-chic Nissan Leaf, a roomy, airy runabout, said to be priced like a Honda Civic, that looks to be this decade’s answer to the Prius. This fall is the scheduled debut of the much-anticipated Chevrolet Volt, a plug-in hybrid that General Motors hopes will save its bacon. And the fourth quarter will see the first shipments of the all-electric Coda, a functional $30,000-something sedan manufactured in China and sold here by a Santa Monica–based start-up.

But some green-car buyers don’t want to give up sex appeal. Tesla Motors, the Silicon Valley start-up that is perhaps Fisker’s closest competitor, has sold about 1,000 of its ultra-sporty, electric Roadster (0 to 60 in 3.9 seconds) at $109,000. Audi, Mercedes and BMW all have EVs or hybrids in the works, and Porsche recently unveiled its 918 Spyder plug-in hybrid concept.

But the most anticipated debut of all—the one that has inspired real curiosity among the diehards who like their cars throaty and powerful—will be the Karma, unveiled as a concept car a little more than two years ago and scheduled for production late this year. The car represents a nearly billion-dollar bet on the future of American automaking. It’s an attempt to create, from scratch, an American car company that will defy history merely by surviving. Not only that, the company actually plans to export cars to Europe and Asia. And it all stems from the outsize ambition of Henrik Fisker. “He’s become very important to this industry,” says an executive involved in the electric-car business. “I don’t even think he realizes how important he is.”

The federal government believes in Fisker. Last September, the Department of Energy awarded Fisker Automotive a $529-million loan to finish the Karma and begin work on its next car, the more affordable four-door code-named Nina. Fisker hopes to sell 15,000 Karmas, and then a whopping 100,000 Ninas. Last June, Henrik Fisker made the cover of Forbes, which dubbed his company “The Next Detroit.”

But this isn’t just a product release. It’s the company’s first ever, incorporating technology that no one, including the giants of automotive engineering, has perfected yet. Which is why Fisker’s secrecy is worrisome. Some are leery of Quantum Fuel Systems Technologies Worldwide, a little-known company that created the powertrain with Fisker. And Fisker is on its third battery supplier in three years. A mishap in a Fisker—or any other EV—could cripple the whole segment, pushing buyers and investors away. “There are 750 gas-car fires every day,” an EV engineer told me. But with battery-powered cars like the Karma, “one single failure will be headline news.”

The company has a highly respected founder, attractive prototypes and a half-billion-dollar government loan. But is Fisker’s sleek, expensive vision of an electric vehicle a forecast of the future, or the kind of rarefied concept that litters the past?

“Anybody can draw a f- -king box,” says a car-company executive who has observed Fisker closely. “What matters is what’s inside, the powertrain that makes the thing go. And nobody has seen that yet.”

NO DOUBT WHATSOEVER

Fisker’s offices in Irvine, California, seem very quiet for a company trying to put vehicles on the road in less than a year. I count only about a dozen employees, and about the same number of cars in the parking lot (a spokesman says 28 employees work there, with another 30 on the way from Fisker’s just-closed Michigan office). Upstairs, there are vast expanses of empty, carpeted office space. But when I meet the 46-year-old Fisker, his unlined face and deep intonation betray no feelings of doubt whatsoever. And then I see why. It’s the car.

The Karma concept prototype sits in the lobby. It’s beautiful, like a long-limbed woman lying on her side. I linger for a moment before being ushered past a fingerprint-identifying security system to a back room filled with clay models, prototypes and disembodied chassis. In one corner sits a newer, shorter version of the Karma, the Sunset hardtop convertible, which Fisker announced last year. I get to sit inside it for a luxurious few minutes. The other six Karmas are off at various car shows or test labs, but I spot a prototype of yet another new model, a follow-up version of the Karma, hidden beneath a tarp. It looks to be some sort of crossover or quasi-SUV, but my queries go nowhere and the tarp stays on. “Whenever we reveal something, other car companies copy us,” Fisker says later. “Why should we give them a head start?”

Despite its Zen moniker, the Karma is a product of the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan. In 2004, Quantum created a hybrid “stealth” military vehicle called the Aggressor, designed for high-risk Special Forces missions. A battery- and hydrogen-hybrid runabout, like a drag-racing green jeep, the Aggressor could be dropped behind enemy lines, zoom into action on silent electric power, with a minimal thermal footprint—and then get the hell out of there in hydrogen or electric mode.

Quantum built a single prototype for the Army, on a $1-million contract. “They loved it so much, they wouldn’t give the vehicle back to us,” says Quantum CEO Alan Niedzwiecki. But the Aggressor never went into production. Its propulsion system married an electric motor to a sizable battery pack, plus a backup hybrid engine that powered an electric generator to extend the range (the powertrain of the Chevy Volt is similar). Later christened Q-Drive, the system delivered a whiplash-inducing 1,700 pound-feet of torque yet got 80 miles per gallon. Someone had to want it.

In 2007, Niedzwiecki met Fisker, just past 40 and already, after his stints at BMW and Aston Martin, an automotive legend. Fisker and his partner Bernhard Koehler had formed Fisker Coachbuild, a boutique shop that designed and re-skinned high-end luxury cars, but that business was drying up and they were looking for something new.

At Quantum’s Orange County offices, Niedzwiecki showed Koehler and Fisker a video of the Aggressor ripping donuts—with no engine noise. They were impressed. “It could go in quietly, blow everything up, and then use hydrogen to get out,” Koehler recalls.

Long, low and wide, the Q-Drive was perfectly suited to Henrik Fisker’s own design sensibilities, which formed early in his childhood in Denmark. His family was once tootling along in their pokey Saab when a Maserati Bora whooshed past. The incident made a huge impression on him. “In primary school, I was always drawing cars instead of taking notes,” Fisker says. He went to design school in Switzerland and spent his career designing exotic sports cars.

But soon he started thinking about hybrids—and the threat they posed. He found it astounding that Leonardo di Caprio was driving a Prius. (“Here’s a guy who could drive any car he wanted to!”) He still winces at a snub by Prince Albert II of Monaco, who refused to be photographed with one of Fisker’s six-figure, ultra-limited-edition luxury machines. From now on, the prince announced, he would be photographed only with “green” cars. Fisker worried that gas prices and global warming were about to consign his work to history.

“I started thinking, what are my children going to be driving in 10 or 20 years?” Fisker says. “Some little three-wheeler commuter cars that are all the same color, they all have 20 horsepower, they all have a speed limiter of 40 miles an hour, and they all have a number? I don’t want to do that. I still want to drive a cool car that’s full of power and having fun. I don’t want to have a number that’s trying to be a car.”

The Fisker Karma debuted at the Detroit Auto Show in January 2008, and although it was just a shell with no motor and fake buttons on the dash, it made big news. One of the industry’s most storied figures was aiming to be the next major American car company. And the Karma did not fit anybody’s idea of an electric car. It wasn’t small or meek. “I’m not interested in saying, here’s a car that’s smaller and slower and doesn’t go as far, and it’s green,” Fisker says. “On the road, they won’t mistake it for anything else. People will wonder what sort of supercar is going by.”

In building the prototype, the company had spent its initial $5 million in funding and needed more. Fisker found its angel in Ray Lane, a former COO of Oracle and now a managing partner at the Silicon Valley venture-capital powerhouse Kleiner Perkins Caufield & Byers. Lane was looking for an electric-vehicle investment, and Fisker made him a believer. “I looked at all the projects out there,” Lane says, including Tesla, Coda and Aptera Motors, a California-based company that hopes to sell an aerodynamic three-wheeler to the U.S. market. For all their differences, those electric vehicles have to be small and lightweight in order to have a useful range. The Fisker design, with its range-extending engine, was both useful and possessed over-the-top sex appeal. “I tried to find where the compromise was in owning an EV called Fisker,” Lane says. “There wasn’t one. I haven’t met a human being yet who didn’t want to own one.”

UNDER THE HOOD

The company is tight-lipped about specifics, but it’s possible to piece together a pretty good picture of what will be inside the production-model Karma. From its appearances at auto shows, we know it’s big: 196.7 inches end-to-end, and a strapping 5,800 pounds, a bit more than a Rolls-Royce Ghost. In part this is because of its dual drive system, with the twin electric motors in the rear and the auxiliary gas engine up front. A heavy-duty lithium-ion battery array, crammed into the large hump running down the center of the passenger compartment, packs enough juice to move the metal 50 miles under normal driving conditions—which is about as far as most Americans drive in a typical day. After that, the two-liter GM Ecotec engine kicks in, not to power the wheels, as in a conventional hybrid, but to generate electricity that feeds the twin electric motors in the rear. So unlike an all-electric car, which has limited range, the Karma can drive essentially forever, with occasional stops at a gas station (it averages about 300 miles between fill-ups).

Although they add weight, the dual drive systems help balance the car’s front and rear. The small gas tank means the rear end can be shorter and sportier, a proportion Fisker favors. And the direct connection between electric motor and rear differential means it can accelerate from 0 to its top electric speed of 95 mph (125 under gas power) as if in one gear. “You’ll feel the instant power, the smooth power,” Fisker raves.

A paddle to the left of the steering wheel lets the driver shift from all-electric “Stealth” mode (a vestige of its military origins) to gas-hybrid “Sport” mode, which affords the car’s full power for hills. In Stealth mode, the Karma could be allowed to drive in sections of certain European cities, like Munich, that have imposed low-emission zones. This is a key factor, Koehler says, in making the Karma export-friendly. “We expect to export 60 percent of our vehicles,” he says. “We don’t just design for the American market.”

Another paddle on the right side of the wheel lets the driver operate the three-level regenerative braking system, with one setting for normal city driving, a second level for hilly areas, and a third—which can recharge the battery in as few as 10 miles—for long descents.

Fisker’s business model depends largely on outsourcing parts, even the seats. “You can go and engineer a new seat, and it will cost you $20 million,” Koehler says. “We didn’t do that.” The air-conditioning system comes straight from GM, along with roughly 200 other miscellaneous parts that Fisker purchases at cost under a special agreement. Valmet Automotive, a contract manufacturer that also makes the Porsche Cayman, will assemble the Karma in Finland.

Yet nothing about the car feels mass-produced. It’s an indulgence. It offers silent electronic door latches and a solar-panel roof that helps run the AC fans and fill the battery (adding 200 charge-free miles per year). The most expensive trim level is called Eco-Chic, with natural-fabric seats, ultrasuede on the dash, and wood trim recovered from California forest fires—not a single square inch of leather. “It’s for the vegans,” Koehler says, and it will set you back roughly an extra $7,500 above base price.

The cockpit is remarkably simple. The dash consists of a 10.2-inch touchscreen that controls everything in the car. There are only three actual buttons, for the glove box, hazard lights and door locks. A small knob switches between drive, neutral and reverse. The seats are roomy, and the passenger compartment big enough for four real adults (although the battery hump somewhat limits rear-seat make-out potential). And for all its muscular good looks, the Karma’s drag coefficient comes in at just 0.31, only a tad less slippery than the Prius’s 0.25.

The Karma is exciting—just standing in front of the prototype fires up something primal. But it’s also not for everyone. I’m 5’11”, and when I sink into the driver’s seat, it’s like drowning in a sea of hood. For me, raised on a steady diet of Volkswagens and Hondas, it’s too low, too long, too wide. It’s an open question, then, whether it will attract 15,000 buyers with a spare $87,900 (less a $7,500 federal tax credit) and whether that will, in turn, lead to mass-market success. “High-priced electric vehicles have a limited market,” says former GM chairman Robert Stempel. “To make EVs practical, we need affordable vehicles.”

“I don’t know who made a rule saying you can only appeal to a mass market if you are boring,” Fisker counters. His next model, in fact, is a four-door, roughly $47,000 jazzed-up family sedan, to be made at a GM plant in Delaware that Fisker is buying for a mere $18 million and will retool with the Department of Energy loan. Fisker spent more than $250,000 on lobbying in 2008 and 2009, money that turned out to be well spent, even if Vice President Joe Biden did say more than he should have at the signing ceremony. Biden revealed that Fisker hoped to sell 100,000 per year, and that crossovers and coupes were next; 100,000 is about the number of BMW 3-Series, a popular model from an established brand, sold last year in the U.S.

FIGHTING FOR THE HIGH END

Fisker is not going to have the luxury green-car market to itself. A few months before the company won its federal loan, the Department of Energy announced a $465-million loan to its main competitor, Tesla, to build its own four-door family sedan, the Model S. A billion dollars in taxpayer money is now riding on whether two competing EV start-ups can find traction at the high end of the car market. (The Obama administration, meanwhile, gave Nissan another $1.4 billion in loan guarantees to build the Leaf in Tennessee.)

The high-end EV industry is small. So small that Tesla once hired Fisker Coachbuild, in 2007, to design the Model S. Fisker showed up at Detroit a few months later, in 2008, with a green car of his own, the concept Karma. Tesla executives were stunned. “When they pulled the sheet off, all the Tesla people went running for their phones,” says an observer. “It looked exactly like what Fisker had designed for Tesla’s Model S.”

Tesla sued Fisker, accusing him of stealing trade secrets. The case settled in late 2008, with Fisker awarded more than $1 million in fees and costs. “That lawsuit was all about executive egos,” a Tesla official says. A Fisker insider is less diplomatic: Tesla co-founder Elon Musk, he says, “is just a brat.” Tesla, for its part, went out and hired star designer Franz van Holzhausen from Mazda, in a clear attempt to compete with Fisker.

But Tesla and Fisker, though fiercely competitive, want to create an industry between them. They share a business model that owes more to Silicon Valley than Detroit. And with none of Detroit’s legacy costs, they are both far leaner than GM could ever be. “We want them to succeed,” a Tesla exec told me. The Fisker people expressed similar sentiments.

Can a new market support not just one but two start-ups selling high-priced electric cars? Both Fisker and Tesla are relying on a kind of trickle-down progression, where high-end buyers lead the way, creating economies of scale that ultimately bring prices down. “It’s like plasma TVs,” Koehler says. They started out expensive, and now everyone has one.

But the new TVs were introduced by established, stable companies, not start-ups gambling on a single product and living investor-to-investor. One condition of Fisker’s DOE loan was that the company had to raise roughly another $150 million in matching funds. Fisker propositioned its own suppliers for investment, tapping battery maker A123 Systems for $23 million; A123 became Fisker’s lead battery supplier around the same time. A competing battery maker, EnerDel, declined to invest. “We just couldn’t get there, as far as the valuation of the company was concerned,” Charles Gassenheimer, the CEO of EnerDel’s parent, Ener1, told a panel at a Washington, D.C., electric-vehicle conference in January. Then he hushed the room by warning that a “high-profile bankruptcy” could kill the EV sector.

There are also serious questions about Quantum, Fisker’s development partner, which created the Q-Drive and is responsible for the vital software system that synchronizes the Karma’s batteries, inverters, motors and braking system. A Fisker insider hints that once the Nina goes into production in 2012, Quantum may no longer be necessary as a development partner, and the two companies will part ways.

Perhaps it will all work out. The Q-Drive, it turns out, has in fact been operating for more than a year now—in two GM pickup trucks secretly tooling around Southern California. “We’ve put thousands of miles on them without anybody knowing,” Koehler says. But my requests for a test drive in a secret pickup were turned down.

TWO WAYS TO GET THERE

Late in the day, I leave Fisker and make my way up the 405 to Santa Monica, to visit a very different electric-car start-up. Housed in a former Saturn dealership on Wilshire Boulevard, the offices of Coda Automotive are a hive of activity compared with the hushed, empty spaces at Fisker. Young, casually dressed engineers are everywhere. Although it’s almost 5 p.m., nobody shows any sign of going home anytime soon.

I prepare to be refused a ride in their product, but within minutes, I’m sitting in the passenger seat of a prototype Coda sedan, whizzing up a side street with CEO Kevin Czinger at the wheel. Built on a reengineered Mitsubishi chassis, it looks like my rental. I don’t feel like James Bond. And then Czinger says words that would make Henrik Fisker fling his Gucci shoes. “It’s a car,” he says with a shrug. “Except it’s quiet, it uses zero gas, and it’s safe and affordable.”

Perhaps the least-known EV start-up, Coda will sell this modest sedan for approximately $30,000. The Coda was created from the inside out—it’s an engineer’s car—starting with a high-energy-density lithium battery system that Coda engineers created with components from Saturn Electronics in Michigan. “In an accident, these will not smoke, much less explode or burn,” says Czinger, brandishing an aluminum-sheathed battery cell at a conference table in his office. There are no trophies here, no fancy suits, just a Bob Marley poster on the wall. Czinger uses the phrase “safe and affordable” as often as possible.

Compared with Fisker and Tesla, the company is a shoestring operation, with a scant $80 million in venture capital and no government loans. Yet the Coda sedan is almost finished, Czinger says, except for fine-tuning the traction-control and airbag systems. The car itself will be assembled by one of China’s biggest automakers, but Czinger estimates that about a third of the Coda’s price tag will pay for U.S.-made components. Between the fourth quarter of this year and the end of next year, he plans to produce 16,000 cars, which the company will sell out of small dealerships in at least four affluent California counties. If all goes well, by the time Fisker and Tesla come out with their mid-priced models, Coda will have been on the market for almost two years. “It’s a pretty plain car,” Kleiner Perkins’s Ray Lane, who once considered investing in the company, told me. Then again, maybe that’s the point.

Will the future of the automobile look more like the Coda, or the Karma? Will the next generation of cars tap into our fantasies, like the Karma, or will those bloated designs simply wither away—along with their role as a totem of sex and success—in the shiny, silent EV Age?

I keep coming back to something I heard from Tesla designer Franz van Holzhausen. Consider that with no engine, no exhaust and no gas tank, an electric vehicle doesn’t even really need to look like a car at all. The battery and motor drive of the Tesla Model S all fit into the floor of the vehicle; instead of an engine under the hood, there’s a trunk. “It’s like a skateboard,” van Holzhausen said. “All the rest of the car is opportunity space.”