We expected efficiency to be the key challenge as we constructed our cross-country, ultralight electric vehicle. After all, we’d decided the car would use no more electricity than a continuously burning 100-watt light bulb. But durability turned out to be equally important. This car wouldn’t be like the high-efficiency concept EVs that are confined to indoor tracks at universities and research facilities–this would be taking me and my son over mountains. Lots of mountains.

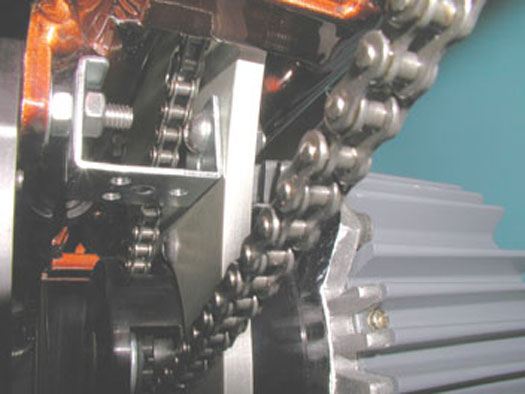

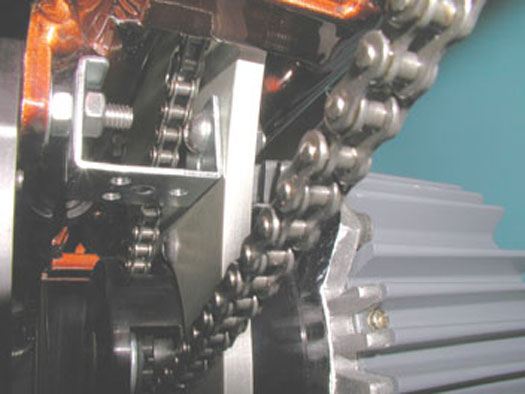

We were pretty confident that our vehicle’s welded frame and chain-and-sprocket drive system would hold up to the demands of hard daily mileage. The car was designed so that anything that did fail could be replaced with off-the shelf parts sourced from a bike shop or garage. The remaining part, one of the most important, was the electric drive, and we looked long and hard at the possibilities. The two most viable options for the electric drive seemed to be hub motors, which would be integrated into the rear wheels, or a stand-alone motor that tied into the vehicle’s existing chain drives.

Both systems have their advantages. Hub motors would allow for a cleaner, sleeker build, and the latest generation of hub motors has a surprising amount of low-speed torque for hill climbing–important, as we’d be going over several imposing mountain ranges, from the Appalachians to the Ozarks to the Rockies. But research showed that a slower-turning hub motor would likely require more power than a faster-turning stand-alone motor for a given hill climb, and that the off-wheel motor could be geared down for low-speed crawls up the numerous steep hills and mountain passed we’d face on our chosen route. In addition, a stand-alone motor could be repaired or swapped out quickly, while a failed hub motor would require us to replace entire wheel unit–not an enticing prospect, considering our route would take us through many rural regions.

Research led us to EcoSpeed, a small company in Portland, Oregon that builds electric-assist bicycle drives. The heart of these drive systems is a high-speed brushless DC motor fitted with an integrated clutch bearing and reduction gear. As compared to the slower-turning motors of a hub system, the EcoSpeed delivers a high power-to-weight ratio, and has earned a reassuring reputation for reliability. The system that seemed best suited to our needs was a 36-volt motor that could handle peak loads of up to 1,000 watts.

The other item that sold us on the EcoSpeed product was the speed controller. Their speed controller, equipped with a Velociraptor microprocessor, is nothing like the rheostat or transistor controllers found on previous generations of golf carts and EVs. It’s essentially a limited function computer that checks in with and reacts to both the motor and the battery bank, and rations power based not only on throttle input but also on battery state, motor load, working temperatures and a number of other factors. Plus, all of those options can be tweaked in the software to deliver maximum power, maximum range, or any combination in between. This is a motor that lets you dictate exactly how it’ll run–and as our needs were unique, that was vital.

The Velociraptor’s ability to ration power strategically would prove key to achieving our goal of 60 miles per day. The unit could also be programmed to limit output to maintain our status an electric-assisted bicycle, which opened up a few nice legal loopholes for us. Federal and state transportation laws don’t differentiate between two-, three-, or four-wheeled vehicles when defining a bicycle, and define an electric-assisted bike in terms of speed and power allowances.

By limiting motor output to a maximum of 1,000 watts–in some states, 750 watts–and by limiting maximum speeds over level ground to 20 mph, we would not be required to meet the more rigid criteria of a Neighborhood Electric Vehicle, or NEV, a low-powered electric vehicle like a security cart that’s limited to certain roads. Being legally classified as a bicycle was definitely a strategic decision: Bicycles and electric-assisted cycles are allowed on the vast majority of secondary roads and city streets nationwide, and can also operate on bike trails, so we’d have no trouble creating a transcontinental route that kept us away from fast-moving freeway traffic.