Scientists have known for nearly two centuries how to transmit electricity without wires, and the phenomenon has been demonstrated several times before. But it wasn’t until the rise of personal electronic devices that the demand for wireless power materialized. In the past few years, at least three companies have debuted prototypes of wireless power devices, though their distance range is relatively limited [see “Power Brokers,” next page]. Then last year, a team at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology set the stage for wireless power that works from across a room.

The key to wireless power is resonance. Think of a wineglass that shatters when an opera singer hits just the right note. When the voice matches the glass’s resonant frequency–the tone you hear when you tap the glass–the glass efficiently absorbs the singer’s energy and cracks. Using magnetic induction and two identical copper coils that resonate at the same frequency, the MIT scientists successfully powered a 60-watt lightbulb from a power source seven feet away. The team called their invention WiTricity, short for “wireless electricity.” Next up: sending the juice even farther and more efficiently.

Power Brokers: Steps Toward a Cordless World

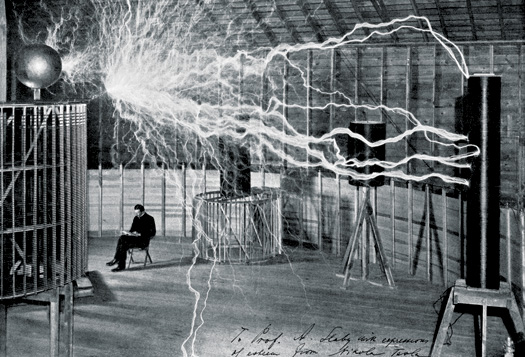

Nikola Tesla:

More than a century ago, physicist Nikola Tesla envisioned a future in which power stations would beam electricity directly into homes and businesses. He built a 20-story transmission tower on Long Island with the goal of demonstrating such a feat, but it never became operational. The Serbian immigrant died a pauper.

Fulton Innovation’s eCoupled:

Like MIT, eCoupled uses paired coils to transmit power, though over much shorter distances. A year ago, Fulton Innovations demonstrated pads and car cups that charge devices placed on or inside them. The company is now working with Motorola and Herman Miller to develop gadget-powering office furniture.

Powercast:

Early last year, the Pennsylvania company Powercast unveiled several prototypes powered by radio waves from a transmitter hidden inside a household object such as a desk lamp. The system delivers a couple watts over short

distances. Wireless holiday lights were available as of the end of last year.

MIT Witricity:

MIT first demonstrated WiTricity midlast year, lighting an incandescent bulb many feet distant from the powering coil. “Electricity [already] comes to our walls,” Karalis says. “We just want to bring it from there to the center of our rooms wirelessly.” The university is in talks with companies interested in commercializing the technology.

FAQs

**

What’s WiTricity good for?

**

It could eliminate that rat’s nest of cords under your desk. You would no longer have to wrangle for an outlet at business conferences. And your home would keep your gadgets constantly powered up.

Can a single transmitting coil power multiple devices?

Theoretically, yes.

Will WiTricity be just like Wi-Fi networks today?

Yes, although like Wi-Fi, WiTricity could be free in some locations and a for-fee service in others. Creating a standard frequency that would allow all your gadgets to be powered at all WiTricity hotspots is an issue.

Will batteries become obsolete?

No. Items (like laptops) that we use indoors might not require batteries. But gadgets like cameras that we use on the go would still need them.

What if my dog fell asleep between the wall coil and my computer?

“Line of sight is not required,” says MIT doctoral student Aristeidis Karalis, who did many of the calculations and predictions for the system. But because the transfer efficiency declines with distance, each room would need its own distributing coil.

**

But will it give my dog cancer?**

Biological organisms are not strongly affected by magnetic fields, and the MIT team believes that safety won’t be a concern. Still, more experiments will be needed.

![A circuit [A] attached to the wall socket converts the standard 60-hertz current to 10 megahertz](https://www.popsci.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/03/18/ZG4NF6UVFADRVJMQ5GX7GXLDDQ.jpg?strip=all&quality=95)

![The receiving coil [C] has the exact same dimensions as the sending coil](https://www.popsci.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/03/18/6NRUB3KO2O6XQMGBIZB73N22WU.jpg?strip=all&quality=95)