At this point, it isn’t necessarily news when a genome publishes—even six years ago, Carl Zimmer pointed out the Yet-Another-Genome Syndrome (YAG) in science journalism. The technology for genome sequencing, after all, continues to get cheaper and faster, making it increasingly easier to find the time and funding to sequence increasingly obscure research organisms.

Still, two papers published today that describe the bed bug genome, which I personally think is exciting. (Can you blame me?) The work comes from two separate groups: one led by the American Museum of Natural History and Weill Cornell Medicine, and the other by i5K, a consortium of researchers who plan to sequence the genomes of 5,000 insect species. The groups published simultaneously in Nature Communications. For more on the papers and why they are interesting—and why I don’t think they’re YAG—check out my story at The Verge.

For this post, I want to talk about the actual bugs in the bed bug genome projects, because they have a story as well.

In 1973, an army medical entomologist named Harold Harlan stumbled upon a bed bug infestation in some barracks at Fort Dix, New Jersey. Bed bugs were quite rare in the U.S. at the time—so rare that Harlan, in all his years of training and work, had never seen live specimens in person. It was his job to hire someone to wipe out the population, so the army recruits who were staying in the barracks could get a break from the bites. But he found the bugs so intriguing and novel that he wanted to save some to study in his spare time. He collected a couple hundred into some Mason jars and took them home.

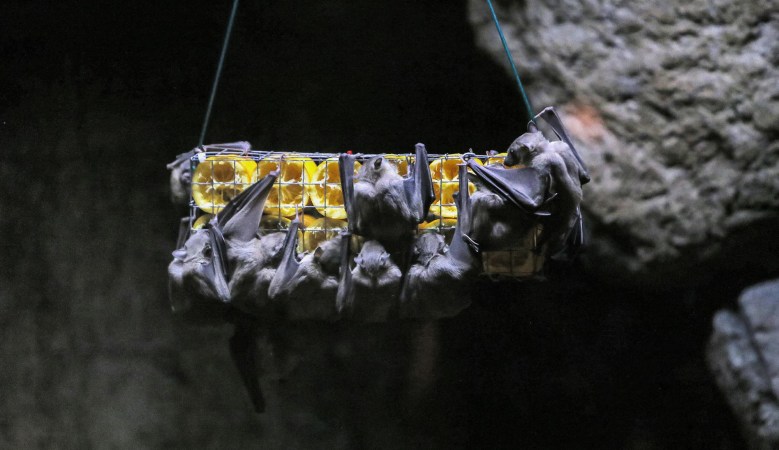

Bed bugs only eat blood, and this particularly species, Cimex lectularius, primarily feeds on humans. The easiest way for Harlan to keep his new research subjects alive was to let them feed on him. He took a pair of his wife’s old nylons and stretched them across the mouths of the jars, so the bugs couldn’t escape, and then held the jars against his arms and legs.

Harlan continued this for decades (even today he has an estimated 5,000 bugs, which he still keeps in jars and feeds every month or so). When entomologists began encountering bed bugs again in the late 1990s, in the earliest days of the resurgence, they asked Harlan for bed bugs so they could build up populations in their own labs.

Harlan’s bugs have been sequestered from pesticides since he collected them four decades ago; unlike bed bugs in the “wild” (aka our homes), his are completely vulnerable to the chemicals. This has proven handy for entomologists who are trying to figure out just how insecticide-resistant bed bugs have become, because they have a baseline for comparison. For example, research that published last week revealing the bed bug’s resistance to neonicotinoids used the Harlan strain.

Harlan’s bugs are also good for genome sequencing. For starters, the fact that the bugs are susceptible to insecticides provides another baseline, this time for genetic comparisons. Now that researchers have the whole genome of the Harlan strain, they can sequence insecticide-resistant strains to see how the genes responsible for the resistance have changed. This could hint at new ways to control the bugs. Harlan’s bed bugs are also quite inbred, since they haven’t mingled with other populations since he collected them in 1973, which also helped the genome work. Bed bugs are so small that it’s not possible to pull their genome from a single specimen, so researchers crush up many bugs together and figure out the genome from that genetic soup. The more closely-related these bugs are, the easier it is to stitch together their genetic material into a complete genome.

I caught up with Harlan, who is now retired, last week to see what he thought of the new papers. He pointed out some differences in how the two groups fed their populations. The bugs from the i5K group were raised on modified rabbit blood with custom artificial feeders. The AMNH team used bugs raised by Louis Sorkin, an entomologist at the museum who, like Harlan, feeds the bugs on his own blood. Harlan pointed out that the differences in feeding may have led to slight differences in the genomes: “The blood sources they used may have affected the expression of certain proteins and enzymes.”

As for the fact that his bed bugs were the first in the world to have their whole genome sequenced, he was pretty modest. “I’m pleased they were helpful, and I was pleased to be able to provide them,” he said. “Other than that, I haven’t done any of the work.”

As if hand-raising bed bugs for more than 40 years isn’t work.

Additional reading:

Bartley and Harlan, “Bed Bug Infestation: Its Control and Management,” Military Medicine, November 1974