Up until a few months ago, most Americans had never heard of the Zika Forest in Uganda, or the virus that bears this region’s name. Today, news of the infectious disease is spreading across the country sparking fear and concern. The mosquito-borne virus has gripped many parts of Brazil and has been found in many adjacent countries. It now threatens the United States as transmission has already been found in Puerto Rico. At this moment, there have been no locally-acquired cases in the rest of America but that may change with the coming spring and summer months.

Zika virus seemingly has come out of nowhere although in reality, this situation is not unexpected. Much like other generally non-lethal viruses spreading across the world, such as Chikungunya and West Nile Virus, this particular pathogen hasn’t gained significant attention in the public health realm. Indeed, if it wasn’t for the suggested link to microcephaly, little would be done to better understand its biology, pathogenesis, or migration patterns.

Now that we know about the possible secondary effects of Zika virus on the fetus, the public health spotlight is squarely on this virus. Unfortunately, due to a general lack of research, few questions have concrete answers. Instead, speculation and theory are dominating the discussion while the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) and others do their best to quell fears using whatever knowledge they have. All told, this is the perfect recipe for an epidemic.

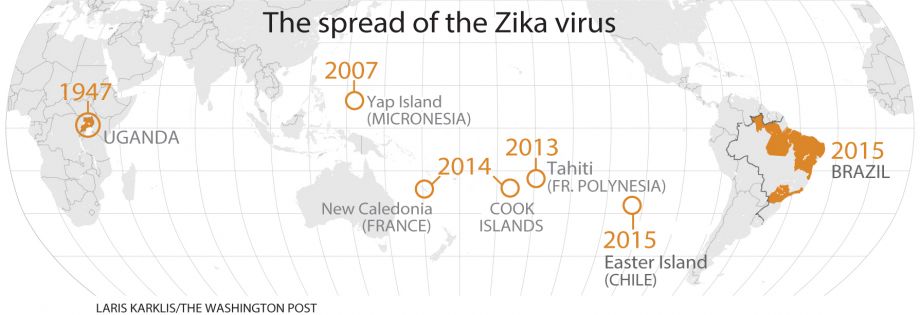

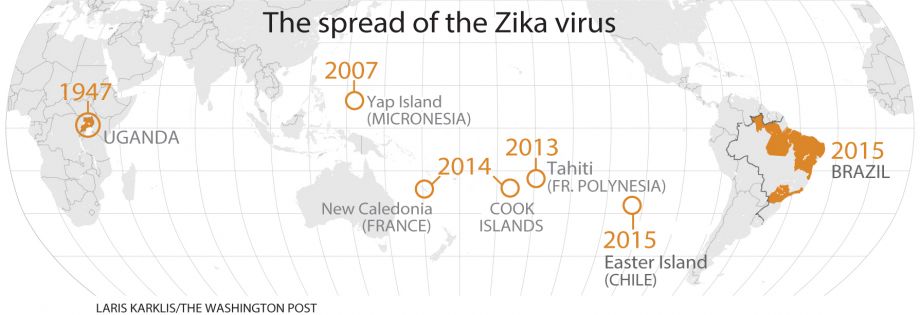

Of course, epidemics usually don’t just happen in an instant and this was the case with Zika. Although over the decades since its discovery in 1947, the virus gained little public attention, some researchers tracked its movement across the globe. It slowly spread across Africa to the Middle East, and eventually into Asia. During this time, cases were sporadic with little signs of an epidemic nature.

Then, in 2007, the situation changed as migration began to speed up. First, it was Micronesia and eventually South East Asia were afflicted. Further analysis suggested the virus was still infecting at very low levels and offered few consequences in the short and long term. There was no need to worry.

Then in 2008 a rather strange case of transmission in absence of a mosquito vector was noted. A scientist working in Senegal contracted the virus and then infected his wife after he arrived home. This apparent sexual transmission of the virus suggested a greater scope of infection within the body and possibly, an opportunity for viral evolution to improve virulence. This transmission was again seen in 2013 suggesting the 2008 cases were not unique. By 2015, sexual and other routes of human to human transmission became a concern as a result of detection of viral RNA in serum, saliva and urine. Although the virus most rapidly spread through mosquitoes, this data suggested a secondary path could lead to even greater spread.

The data also caused another serious concern regarding pathogenesis. With Zika apparently spreading within the body to places not previously encountered, the concept of a viral evolution became much more apparent. But as to what type of adaptive changes happened, there were little answers. Based on previous genetic analyses from 1968 to 2002, few changes had occurred. The 2007 version had some mutations but nothing to explain the larger spread of the virus in the body. If something had happened, it would have been after these dates.

Due to a lack of cases and samples, little could be done to determine if any shifts had occurred. The only option was to continually return back to the original samples and assess if anything had been missed. Then, in 2014, a break came when a new sequence of Zika virus became available. Researchers finally could figure out whether any evolutionary changes had occurred over the seven previous years. The sample was also from the first recorded case of perinatal transfer. At the time, however, the potential consequence of this mother-to-fetus transmission was not considered to be a priority.

After the analysis was complete, the results were released at the end of 2015. There had indeed been an evolutionary shift allowing the virus to replicate more rapidly and also potentially spread to other areas of the body. The change itself is minor, a slight difference in the way the virus produces one particular protein, but it was enough to suggest Zika had become adapted to humans and was now a much larger threat than believed.

Unfortunately, the news and warning came too late. By the time the document was ready for publication (without peer-review), the Brazilian outbreak was already in full swing. Not long afterwards, a surge of cases was seen as the once-feared epidemic began to develop into reality. Travel-related cases are being documented around the world and soon, localized transmission either through mosquitoes or sexual contact may lead to establishment of the virus in previously safe locales.

While we now have a better understanding of the Zika virus at the biological level, there is little to be done to control the spread of the virus. All that can be done now is to look towards preventative measures to minimize the risks. The epidemic has started and now we must wait to determine just how far and how bad it will be.