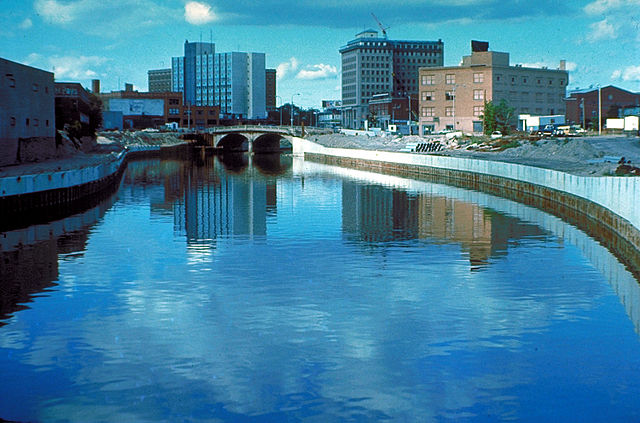

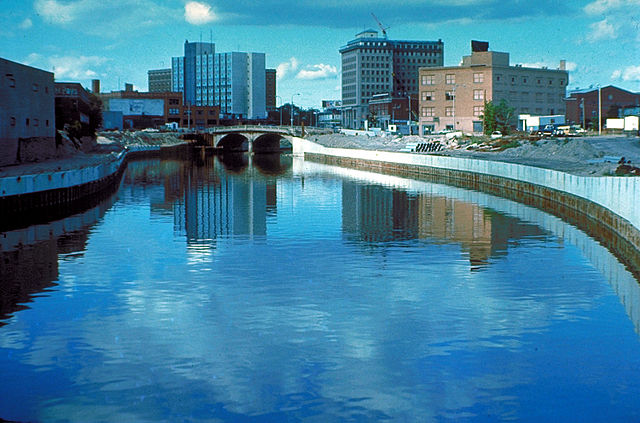

The people of Flint, Michigan have been drinking lead-tainted water for more than a year since the city switched its water source from Detroit’s Lake Huron to the Flint River.

According to the most recent tests, Flint’s water is still undrinkable, with average lead levels exceeding 10 parts per billion in a sample of 271 households (ideally, you want zero lead in your water because of a variety of health impacts). But how did the river water cause this disaster?

What’s in the Flint River?

Lots of chloride ions, for starters. Chloride can occur naturally in rivers but may also be added by road salting, according to Marc Edwards, the lead Virginia Tech researcher testing Flint Water. Because of the chloride ions, the Flint River is 19 times more corrosive than the city’s previous source of water. The river water corroded city pipes, and the corroded pipes leached lead into drinking water.

Flint officials could have avoided the crisis by adding orthophosphate to neutralize the chloride, says Edwards. Half the water companies in the country add this chemical to community water sources to prevent pipe corrosion, but Flint officials skipped that step (which costs $100 a day).

What other problems come from corroded pipes?

Besides lead poisoning, corrosion can bring more bacteria into the water supply. Corrosive water inactivates chlorine (Cl2), a city water supply’s main defense against pathogens (not to be confused with chloride). Even upping its levels of chlorine, which Flint tried doing, doesn’t help, says Amy Pruden, one of the primary investigators in the Flint Water studies.

“It’s kind of futile because the chlorine gets eaten up by the corrosivity of the water,” says Pruden.

The corroded pipes cause more water main breaks, which can bring in more bacteria from the surrounding soil, she adds.

The water chemistry also plays a part in making a comfy home for pathogens. For instance, one hypothesis is that iron can stimulate Legionella bacteria, the bug responsible for Legionnaires’ disease (which causes pneumonia and can especially effect immuno-compromised individuals). Flint, with its corroded pipes, provides plenty of iron and there has been a spike in Legionnaire’s cases the last two years. A total of 10 people have died in those outbreaks.

Could this happen again?

Flint was a perfect storm of mismanagement and malfeasance, but it also illustrates how communities must be vigilant about how their water chemistry affects infrastructure.

Though most cities are proactive about adding phosphate, in some cases it’s not enough to address highly corrosive waters, says Edwards. It is an emerging problem for cities, he adds, most likely due to increasing use of road salt. In portions of the northern U.S., chloride concentration in streams approximately doubled from 1990 to 2011.