One of humanity’s greatest queries has focused on the nature of a change from good to evil. There is no single answer; several possible reasons apply. Julius Caesar, who dramatically asked his friend, “Et tu, Brute?” learned the hard way about the power of opportunity. In the fictional series, Homeland, empathy for a child was the root of Nicholas Brody’s turncoat actions. Finally, there is the longstanding issue of necessity, in which a person turns to crime to deal with environmental stressors, such as a lost job or poverty.

In the microbiological world, the change from a harmless entity, a commensal, to a pathogen has been the focus of many researchers. Not surprisingly, the same three options apply. Streptococcus pneumoniae takes advantage of illness to cause a life-threatening infection. The skin bacterium, Propionibacterium acnes, changes when the skin is treated poorly leaving us with the terror of acne. Then there is Clostridium difficile. At one time, this bacterium was harmless but due to the presence of antibiotics and other stressors, including proton pump inhibitors, it developed not only toxins but resistance to antibiotics.

Whatever the reason, when a bacterium decides to change, the only means to accomplish the action is through genetic evolution. The process may involve altered expression of already present genes, nucleotide mutation in the genetic sequence, recombination events or the acquisition of virulence elements such as plasmids. When this happens, the microbe becomes different in structure and function forming a new strain and quite possibly, a new health problem.

The most widely studied bacterium is without a doubt Escherichia coli. This small rod-like organism is ubiquitous in our world and interacts with us each and every day. Some are harmless, such as the commensal K-12 or beneficial including the probiotic Nissle 1917. But there are pathogens and one of the most prevalent strains is Enteroaggregative E. coli (EAEC).

The bacterium, first described in 1987, is known to cause both singular infections as well as large outbreaks. It is also a major focus for diarrheal illness particularly in children. Unfortunately, determining the mechanisms of evolution as well as the motivating reasons for its appearance have been a mystery.

In 2010, an international team of researchers attempted to find some answers. They looked at 126 isolates from the southwest region of Nigeria to identify a common ancestor and possibly determine a motive. Unfortunately, they came up empty. There was no single EAEC strain; rather it was a compilation of various pathogenic bacteria all showing the same symptoms but with no common reason to change.

In 2013, the EAEC picture was muddied even further. A team of researchers in the United Kingdom analyzed various EAEC isolates between 1993 and 2009. As expected, they found several pathogenic variants but they happened upon non-pathogenic ones as well. Based on this discovery, the presence of this particular strain did not necessarily mean disease. If there had been a common reason for this bacterium to turn evil, it was not all-encompassing.

Now there may be a possible explanation for both the development of the EAEC strain as well as the reason for the variety in pathogenic response. An international team of researchers investigated the origin of the strain and last week revealed their surprising results. Unlike previously believed, there was no single motive but rather, as many as three.

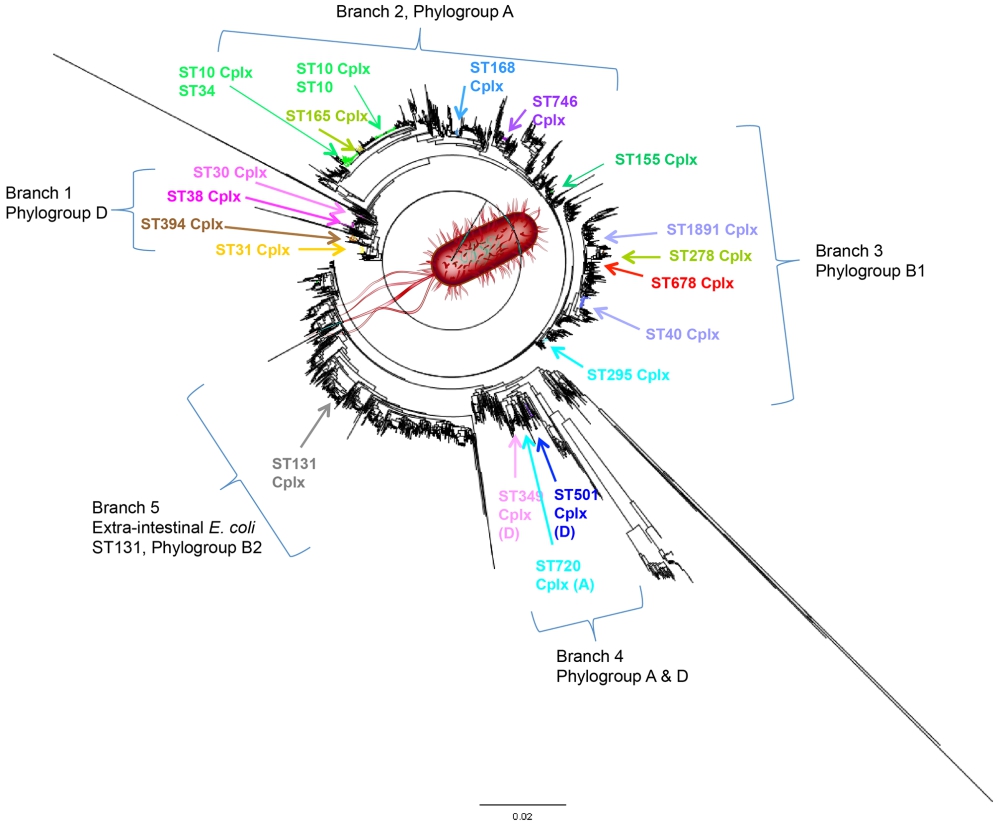

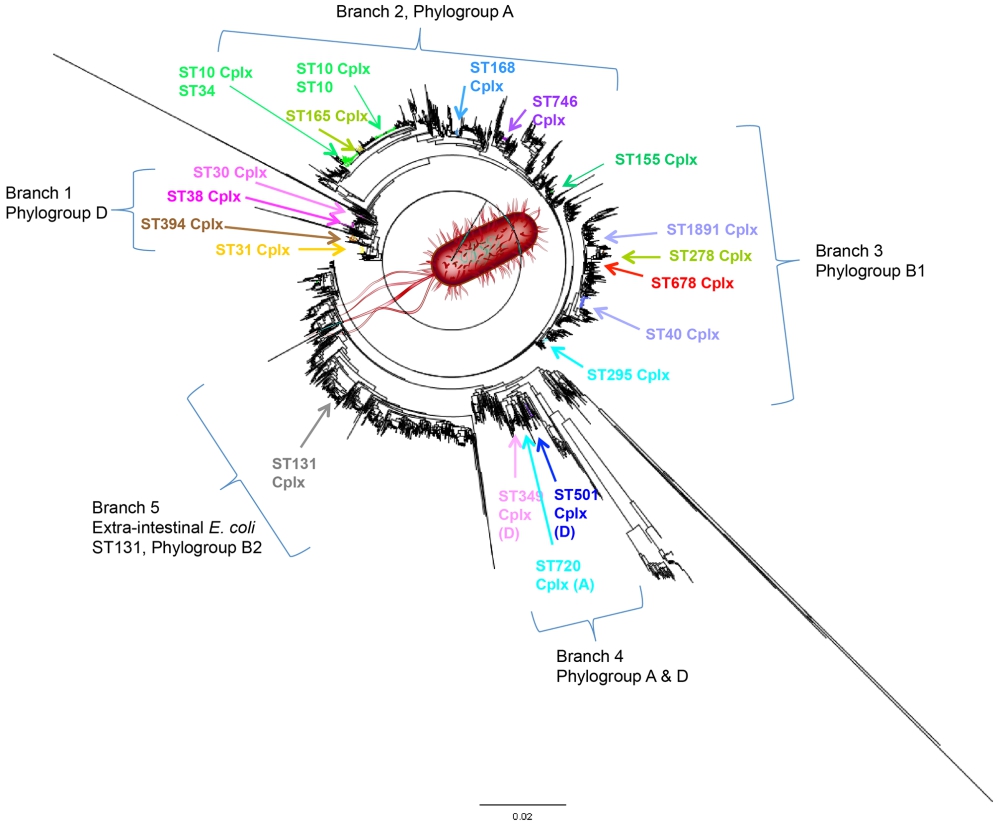

The group focused on 564 strains isolated over the course of three decades. Using a technique known as multi-locus sequence typing (MLST) the researchers attempted to find the answer behind pathogenic motivation. First, was there a common ancestor to explain the development of this strain and second, why did some cause illness why others did not. The task was a tall order for any microbiologist and yet they felt they could finally succeed where others had failed.

In terms of mechanism, the group found a common evolutionary route for pathogenic EAEC strains. Regardless of geographical location, these bacteria arose mainly through recombination in which communication with other strains led to a turncoat outcome. As for the motivation behind the change, the development happened primarily when competition was present. The process was not evil in nature but rather an act of necessity.

With the understanding of both mechanism and motive, the researchers wanted to then take the unusual step of figuring out why only some isolates caused disease. The answer offered an unexpected perspective. Until now, EAEC was thought to be its own separate branch of E. coli but the analysis showed otherwise. EAEC could be found in three separate groups only one of which was considered pathogenic. This meant in essence, the bacteria had been misunderstood; they were not all villains. In fact, most were nothing more than survivalists.

The overall conclusions suggest the profile of EAEC needs to be reviewed and altered. Indeed, isolates do cause disease, but there are harmless and/or helpful ones as well. This distinction has yet to be delineated fully yet a more detailed investigation is clearly useful. After all, when it comes to villains, a proper analysis can help us understand not only why a good person – or microbe – turns bad, but also whether they are actually our enemies or just lost souls.