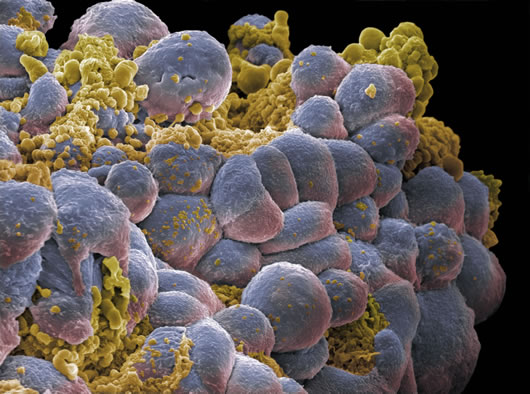

Many people love the look of tan, sun-kissed skin, spending hours in the hot sun (at just the right angle) to achieve the perfect summer glow. But the dangerous effects of sun exposure on our skin are pretty straightforward: evidence clearly shows that repeated exposure to the sun can accelerate skin aging and lead to a greater chance of developing skin cancer.

But it seems unlikely that humans will ever unanimously decide that tanning isn’t worth it. The ultimate hack, then, would be to figure out a way to get that tan without the damaging effects. For the past few years, researchers have been trying to do just that. And in a paper out this week in the journal Cell Reports, they’ve taken a big leap: scientists identified a small molecule that successfully darkens skin without exposure to UV radiation from the sun. A lot more research is needed, but in theory this could give us a new way to create melanin without the sun’s help.

The hunt for a UV-independent tanning method isn’t new. About a decade ago, the same researchers in this new study identified a compound called forskolin; when injected into the skin of mice, it turns on a protein that tells the body to produce more melanin, the pigment that makes skin darker.

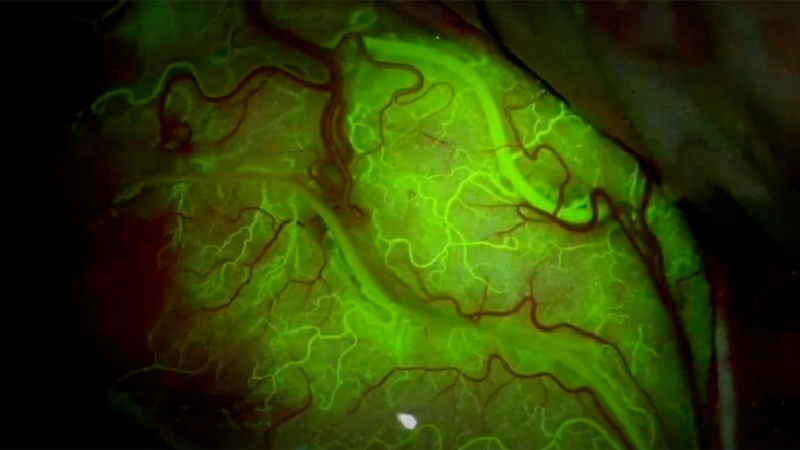

The compound worked fine in mice, but when they tried it out in human skin cells in a lab, the protein failed to make the skin cells darker. As it turns out, humans are incredibly thick-skinned—five times thicker than a mouse’s skin, to be precise. So the researchers turned to different proteins called salt-inducible kinases (SIK), which work similarly but in a different area along the melanin-production pathway. They tweaked those proteins to make them even smaller so that they would fit inside a human’s super thick skin. And sure enough, they seem to work—in a Petri dish, anyway.

This all sounds very promising, but it’s a bit too soon to throw away your sunless tanner. The researchers have only tested these proteins out in skin cells in a lab, not in real people. They will need many further studies to figure out what effect this can have on body function as a whole. In the paper, the researchers note that its use would require careful considerations of safety. While they know that creating darker pigmentation is associated with the lowest risk of most skin cancers in humans, the SIK proteins work by inducing something called the MITF, which is the master regulator of pigment genes. They say that mutating or amplifying the MITF gene can cause cancer in certain contexts. While this process is not likely to trigger any mutations, it’s impossible to know for sure without further studies. So far, in mice studies, they haven’t found any increased carcinogenic risk.

So the outlook for this artificial tanning method is sunny with a chance of future human application. But for now, slather on the sunscreen, cover up, and remember that there’s nothing wrong with avoiding tans altogether.