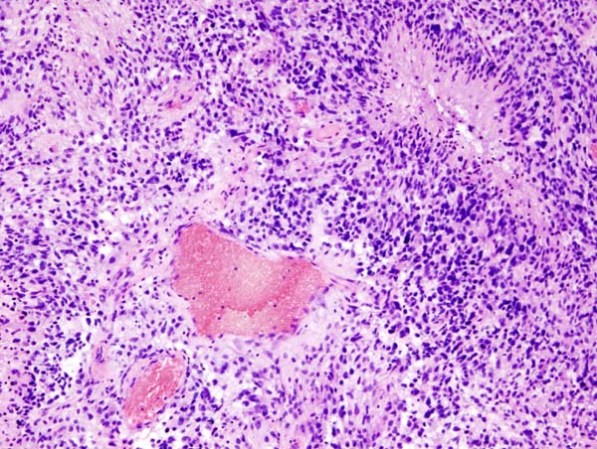

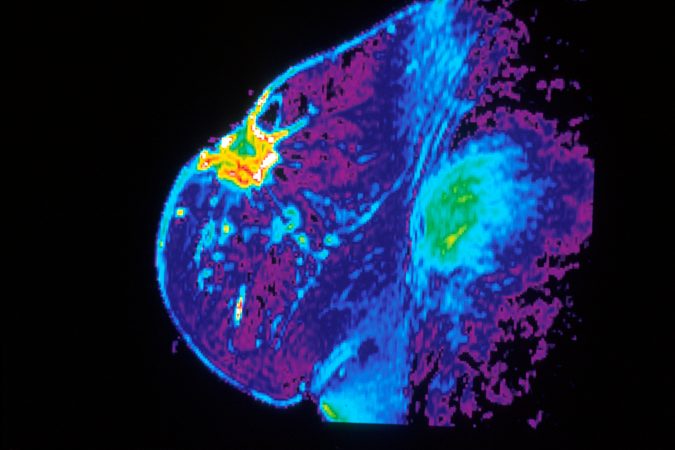

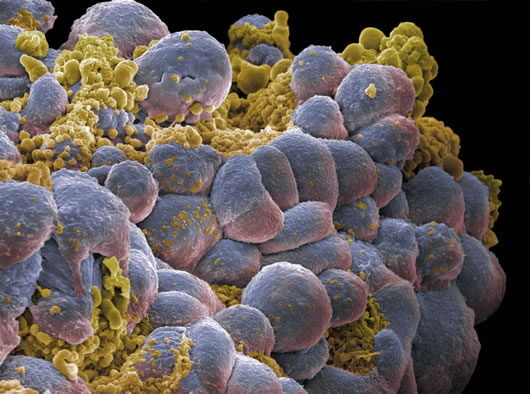

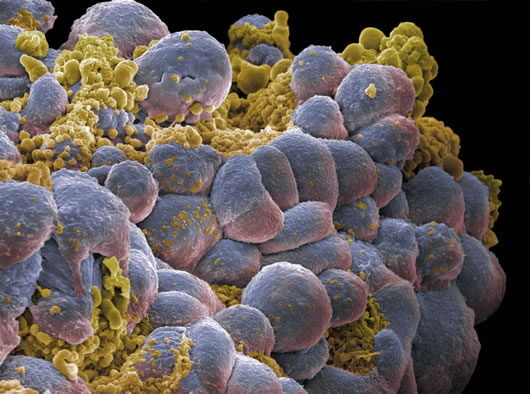

The ultimate goal of a lumpectomy is to remove all the cancerous tissue from a person’s breast while saving as much of the healthy tissue as possible. But that’s even harder than it sounds. Without the ability to look at tissue under a microscope, it’s currently impossible to tell whether the area surrounding a tumor contains cancerous cells or not. Surgeons deal with this by taking samples from around the removed tumor, waiting for a pathologist to look at them, and performing additional surgeries if they turn out to be cancerous. This is not only time consuming and expensive, but also extremely stressful for the patient.

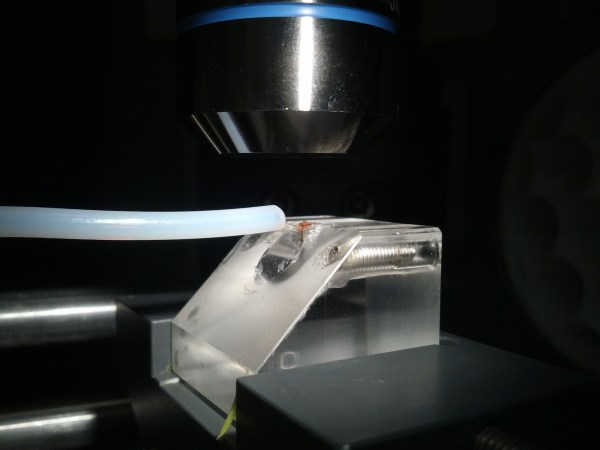

A new microscope developed by researchers at the University of Washington might change that. It uses a super powerful light to optically “cut” through the area and see what’s inside in around 30 minutes, so that surgeons can know whether that tissue sample still contains cancerous cells. If it does, they can go back and remove that tissue, hopefully getting rid of the cancer in one go. The researchers published their work this week in the journal Nature Biomedical Engineering.

Unlike other areas of medicine, pathology hasn’t advanced all that much. To see if a piece of tissue is cancerous, pathologists still need to go through extensive preparation processes—like staining, slicing, and forming tissues into waxy blocks before they can look at them under a microscope. That process can take days, and it also limits the number of diagnostic procedures you can carry out on a single sample. Once something is sliced and stained, it can’t be retested for another disease or sent for genetic testing, which is an important part of cancer treatment.

Because the new microscope design works quickly and without wrecking tissue, the surgeons can get results during the surgery itself, determine what needs to be done next, and save samples for other tests. The researchers say they are currently testing out the microscope on breast cancer samples, but in the future they plan to use it on other cancers that also involve solid tumors. Even further into the future, they hope to incorporate machine learning algorithms to help pathologists identify cancer more quickly and accurately.