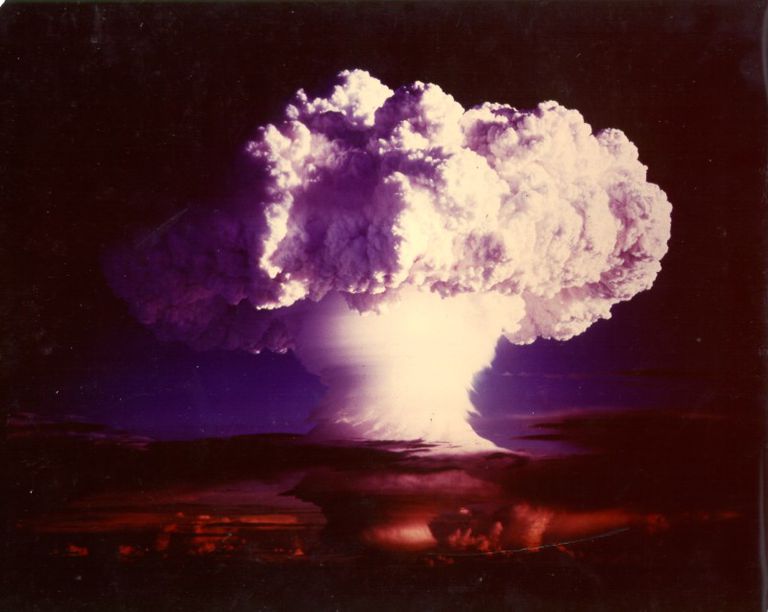

The Doomsday Clock is now closer to midnight than ever before—so close that, instead of minutes, we’re now counting down to metaphorical oblivion in seconds. According to the Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists, we have just 100 seconds to midnight.

Here’s what that actually means.

What is the Doomsday Clock?

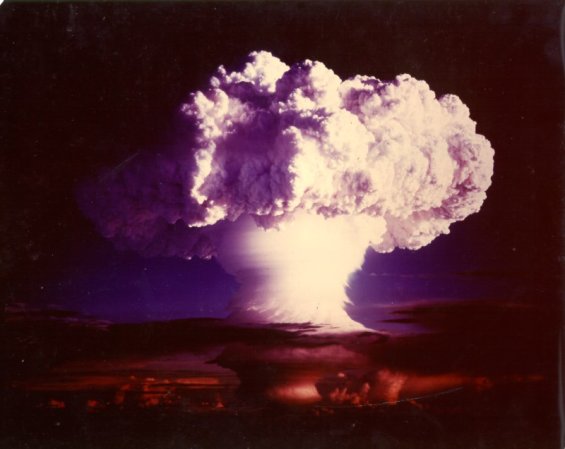

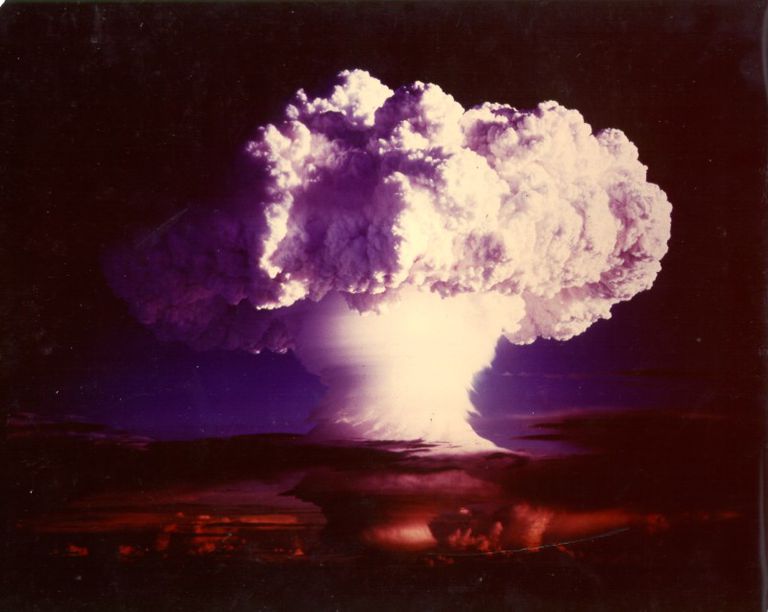

The Doomsday Clock is neither a meaningless art project nor a precise scientific measurement; it’s somewhere in the middle. The graphic was introduced in 1947, when artist Martyl Langsdorf designed a clockface at seven minutes to midnight for the cover of the Bulletin of Atomic Scientists. She picked the time of 11:53 p.m. somewhat arbitrarily, but the idea was to make people think about how much more dangerous life was becoming in the nuclear age. That was rather the point of the Bulletin itself, which was put out by a group of scientists who’d participated in the Manhattan Project as a response to the bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki.

What happens when the Doomsday Clock hits midnight?

We’re not 100 actual seconds from an apocalyptic disaster at this moment, or at any other moment, based on the position of the Doomsday Clock. In fact, during the Cuban Missile Crisis, when the world was arguably perched most precariously on the precipice of nuclear war, the infamous minute hand didn’t move a bit. The clock (which, by the way, does not exist physically—you can’t go visit it, which would probably be the most existentially distressing long weekend one could plan) is meant to remind us that global catastrophe has been just around the proverbial corner from the moment our species entered its nuclear age. It’s not keeping tabs on day-to-day threats; a board of scientists and policy experts convene just twice a year to decide whether it’s time for a tick, and they only make announcements on clock hand movement (or lack thereof) periodically.

What makes the Doomsday Clock tick?

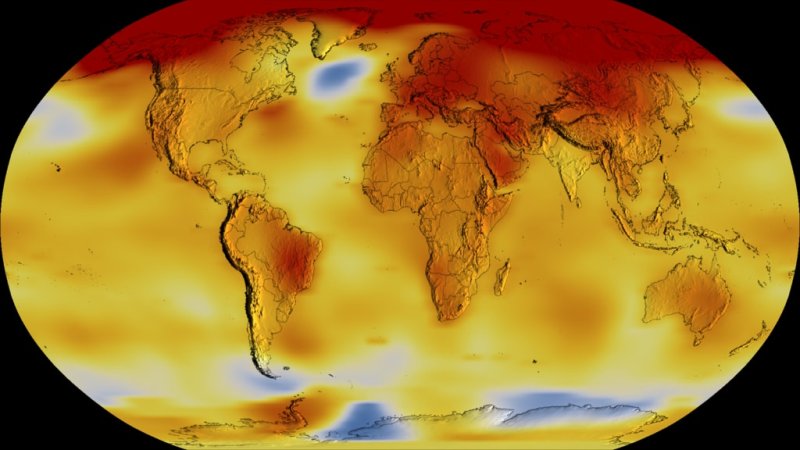

In its original iteration, the clock’s ticking rested on the opinion of just one man: Eugene Rabinowitch, a scientist who edited the Bulletin’s print publication in its infancy. He used his own scientific expertise and that of fellow researchers to determine whether or not it was time to move the clock forward (or back). Now the Bulletin’s Science and Security Board makes the call, along with their Board of Sponsors (which includes 13 Nobel Laureates). The group tries to determine whether the world is objectively more or less safe than it was the year before, and pushes the minute hand forward or back accordingly. Though it was designed to broadcast the threat of nuclear proliferation, the clock-setters started to factor in climate change starting in 2007.

How bad is it that the Doomsday Clock is at 100 seconds to midnight?

Again, this is just a metaphor—no one has crunched the numbers on the statistical likelihood of our obliteration in comparison to its likelihood a year ago. But as a group of experts with a long history of evaluating how our species is doing, the folks behind the Doomsday Clock are worth paying attention to.

In 2018, the Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists ticked the clock forward to land on two minutes to midnight—as close as it had ever gotten, and at the same level as it was the Cold War. In 2019, the clock stayed in that position. Now we’ve moved forward by 20 seconds more, pushing us into new territory.

“We are now expressing how close the world is to catastrophe in seconds—not hours, or even minutes,” Rachel Bronson, president and CEO of the Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists, said at a press conference on Thursday. “It is the closest to Doomsday we have ever been in the history of the Doomsday Clock. We now face a true emergency—an absolutely unacceptable state of world affairs that has eliminated any margin for error or further delay.”

The group highlighted the same three factors that influenced their decision in 2018: The threat of nuclear war, the growing catastrophes of unchecked climate change, and the proliferation of disinformation online.

“To say the world is nearer to doomsday today than during the Cold War—when the United States and Soviet Union had tens of thousands more nuclear weapons than they now possess—is to make a profound assertion that demands serious explanation,” the group said in a statement.