We can’t say exactly why you want to save images, videos, social media posts, or other types of information from the internet. We can, however, guess that you’re probably doing it for personal, historical, or accountability reasons. Whatever your goal, grabbing the goods is easy—but knowing what to do with them is tricky.

Compared to other types of records and expressive mediums, the internet is ephemeral. Two centuries ago, anyone who wrote an ill-advised post or sent a “bad tweet” would have had to out-gallop a Pony Express rider or figure out how to trap a very determined pigeon. Today they can just hit delete.

That’s not to say everything that disappears from the internet is bad. Neglected websites go offline, technology goes out of date, and some people just feel more comfortable knowing they haven’t left a years-long digital trail. No matter the gravity, what goes up will eventually come down.

How to save images, video, and social media posts

Just as there are countless reasons for saving data, there are nearly as many social media sites. It’d be almost impossible to go through the steps for snatching information off of every single source, so we’ll cover a few of the big names. You should also familiarize yourself with video capture programs and your devices’ built-in screenshot tools for websites that don’t make downloads easy. Simply recording what’s on your screen may not be as good as getting the original file, but it’s a solid, reliable backup when you can’t.

Downloading images directly

Saving images from browsers is generally straightforward. On Twitter and Facebook, just open the one you want to keep, then right-click it to bring up a menu that includes Save Image As. You may be able to save it directly, but if it suggests a file format your computer can’t handle properly (like WebP from Google Chrome), you’ll need a program that’ll let you open files from URLs, such as PhotoPea. Open the free, browser-based image editor, click File, Open More, and Open from URL. Then paste the URL and hit OK. Finally, go back to File, select Export as, and choose a filetype.

On your phone, you may be able to press and hold on a photo until a menu appears with the option to Save Photo (iOS) or something similar. If you’re using Facebook from a browser, though, you may have to open the image, open the menu (three dots) and tap View Full Size. From there, long-pressing and tapping Add to Photos should work.

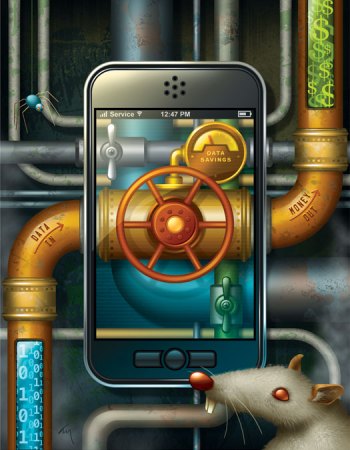

Downloading videos directly

Saving videos is a little more complicated. For videos posted on Twitter, you’ll have to open the tweet, copy the URL, and go to a website like SaveTweetVid or Twitter Video Downloader. Both work the same way: paste the URL, hit Download, and then click Download Video. If it opens in a browser tab instead, just right-click and select Save Video As. Facebook has an option for Save video under the three dots in the top right corner of a post, but this just saves it within Facebook. The actual process is a full story on its own. It’s a similar situation on YouTube, which does not let users download videos.

Witness, a nonprofit that uses video and technology to defend human rights, also has a thorough guide on how to save live video broadcasts.

Screenshots and screen recording

For these and other sites (like Instagram) where there are no straightforward saving options, the simplest choice is often to save a screenshot or record your screen. On macOS, use Cmd+Shift+4 to bring up the screenshot tool. Then click and drag a box around whatever you want to capture. Windows used to have Snipping Tool, but that’s now part of Snip & Sketch. Open the program, click New, and choose Snip now (or one of the other time-delayed options). Click and drag over what you want to save. On iOS and Android, the options vary depending on the type of phone you have and the operating system it’s running. These tools are also the easiest way to save social media posts.

To record your screen on macOS, press Cmd+Shift+5 to bring up the Screenshot toolbar, and follow Apple’s detailed guide to get it to do what you want it to do. On Windows, you can use the Xbox Game Bar to record any open application (not just games). Beyond that, you may want to consider one of the many free screen recording platforms available.

What to do with data you’ve saved for personal use

Whether you’re saving tagged photos of yourself from Facebook or building an impressively curated library of memes, the main thing to consider is redundancy. Back. Everything. Up. Twice (or more) if you want to. That way, if one hard drive fails, you have copies somewhere else. There’s not much more guidance we can give. You do you.

What to do with data you’ve saved for historical reasons

Even when we’re not living in “unprecedented times,” we’re still living through history. You may think that photos of small demonstrations, construction, demolition, or other events in your neighborhood or small town pale in comparison to occasions with national or global effects. However, your local historical society or museum may think differently.

Sometimes, these institutions put out requests for information or records. But if you have something that may be of historical interest, you can also reach out yourself.

Online, there’s the Internet Archive, a nonprofit library of websites and other media. One of its best-known tools is the Wayback Machine, which shows historical snapshots of billions of web pages. It doesn’t save everyone’s social media accounts, but it does save some (it has saved President Donald Trump’s Twitter account nearly 50,000 times in the past 12 years, for example). If you find a page hasn’t been saved, you can ask the organization to archive it. Go to the Wayback Machine’s main page, find Save Page Now, enter the URL of the target page, and hit Save Page.

Saving historical videos and images, particularly of politicians, public figures, and televised speeches may also one day be important in fighting deepfakes. These altered videos and images have become increasingly popular, and they’re only getting more realistic.

What to do with photos and video of alleged criminal activity

In the wake of the riot at the US Capitol, social media was flooded with people publicly trying to identify participants. Not only is this potentially problematic due to the possibility of misidentification, but it could also put you in danger.

It’s also important to consider the ethics of using videos to report potentially illegal acts or human rights violations. Witness has a downloadable PDF that details the responsibility we all have to the people filmed, the video creators, and the audience. You may not want the subject of the video to relive an abuse again and again, dox the person who shot the footage, or cause more widespread trauma.

Once you’ve sized up the risk to yourself and others and still think it’s worthwhile to submit potential evidence to the proper authorities, be strategic. As tempted as you may be to quote-tweet a seemingly damning video with “Uh, @FBI?????” that’s not the best way to go about it. In fact, the agency’s Twitter bio straight-up says “Do not report tips here.” They want you to submit information online or (if it’s an emergency) dial 911. In regards to the violence at the US Capitol, for example, the agency has a dedicated information submission portal. Local police departments may be even less willing to sift through their social media mentions for possible proof of harassment, xenophobia, or other crimes.

![How To Make A Smartphone-Powered Hologram [Video]](https://www.popsci.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/03/18/J2QH4J5SXREARSS45CTPGH2BHA.jpg?w=600)