In Boston, Galveston, and Charleston, high tides regularly bubble up into low-lying areas on sunny days. Floods like that, which would have been rare, or even impossible, three decades ago, happen multiple times a year. Some neighborhoods of Miami flood every few weeks in the spring.

Those floods are often framed as a hint of what climate change will bring to America’s coasts. But they’re also a result of sea level rise that’s already occurred, and a signal of the country’s limited preparedness to deal with more water. The crisis is already here.

Over the next 30 years, average sea level around the United States will be about a foot higher than it is today, according to recent projections from an interagency report released by the National Oceanographic and Atmospheric Administration, based on tighter estimates of sea level rise in recent Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change reports. That, NOAA notes, is almost exactly as much as seas rose since 1920.

See projected sea levels across the US under different warming scenarios.

High tide flooding will become worse over the next 30 years, touching communities that are currently just outside its reach. But, says William Sweet, an oceanographer with NOAA and lead author on the new report, what’s happening right now isn’t just a preview. Sweet lives in Annapolis, Maryland, and says that he regularly gets alerts about flooding on local roads. “When I hear ‘we’re gonna have king tide flooding,’ I say, ‘We’ve had king tides for decades.’ Let’s call it sea level rise flooding.”

A century of rising water

Although sea level rise across the country has accelerated to about an inch every three years in the last 15 years, “The 20th century rate was already the fastest in at least 3,000 years,” says Robert Kopp, a climate scientist at Rutgers University, and a lead author on the IPCC’s most recent climate projections. A recent paper led by a member of Kopp’s team found that the United States’ oceans began to consistently rise sometime in the late 1800s, a few decades after global average temperatures started their upward climb.

The first signals of that change came from water gauges, some of which are more than a century old. The gauges were used to maintain accurate maps of shipping lanes, Sweet says, and over time, cartographers realized that tides were growing slightly higher on average as the decades went on.

The source of sea level rise has changed over the last 100 years, even though the root cause is a warming planet. Some of it has been due to the expansion of ocean water as it warms. But a substantial part of the rise over the last 100 years came from the world’s glaciers. Glaciers react quickly to rising temperatures, says Thomas Frederikse, a sea level expert at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Lab, and an author on the recent NOAA report, but they don’t hold much water overall.

But since the 1990s, meltwater running off of the Greenland and Antarctic ice sheets has become an increasing part of the total. “That’s the opposite of glaciers,” says Frederikse. “It’s very slow, but when it goes, it goes.”

The regions of the US that have experienced the most dramatic shifts are sinking as the oceans rise. The Atlantic coast, which has seen roughly 8 inches of rise since 1980, bulged upwards during the height of the last ice age, and has been dropping ever since. The coasts of Texas and Louisiana, with a foot of rise since 1980, are undermined by groundwater pumping, oil and gas extraction, and the slow settling of coastal mud. On average, the US has dropped four inches, while the ocean has risen eight.

How did coastal communities experience a foot of sea level rise?

High tide floods are now twice as common across the US as they were in 2000. A 2016 study by Climate Central and Kopp found that two-thirds of coastal floods since 1950 likely would not have happened without sea level rise. In Honolulu, between 83 and 100 percent of every flood since 2004 was caused by climate change.

The damage over the next 30 years will be much further reaching. Coastal communities were built high enough above the ocean to give themselves some buffer against rising seas. That wasn’t necessarily intentional, says Sweet—instead, coastal communities were likely building high enough to avoid extreme storms that happened once every few years. That meant that they had slack in the system, and wouldn’t necessarily experience sunny day flooding after a foot of sea level rise.

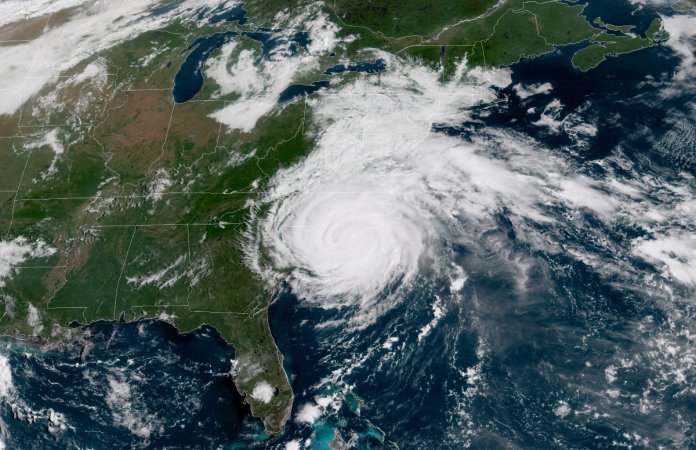

The rise has meant that there’s no longer a buffer against storms. NOAA projects that by 2050, destructive floods will become five times as common. Another foot of water could put more communities—including those on the West Coast, which haven’t been hit by hurricane flooding—in the position of Miami, with regular high tide flooding. “Areas that are flooding now are going to flood more,” says Sweet. “Areas that are right up along the brim that have a flat, exposed population, with a little bit of sea level rise, start flooding a lot.”

See how higher sea levels will play out county-by-county

The scale of that vulnerability varies enormously depending on the scale of climate change. Honolulu could see a foot of sea level rise by 2050 if humans rapidly cut carbon emissions, or closer to two feet if business continues as usual.

Have coastlines responded?

But the impact of sea level rise is about who lives by the ocean, not just how much it has risen. Over the last century, Americans have built more homes on coastlines—oftentimes faster than they’ve built them inland.

That suggests that even a foot of sea level rise hasn’t necessarily convinced people to look for homes elsewhere.

“I think it’s important to bear in mind the difference between post-disaster effects and chronic effects,” says Kopp. Disasters often (though not always) bring in federal money, and create a federal framework for buyouts of flood-prone homes, usually through FEMA. They also produce a natural breakpoint, when a resident of a coastal home might decide to relocate rather than rebuild.

Buyouts for chronic flooding are rarer. One of the country’s first standing buyout programs is in New Jersey. The program, called Blue Acres, started in 1995, and grew with an infusion of federal money from Hurricane Sandy. It purchases homes in any county affected by Hurricane Sandy, as well as properties that have experienced repeated flooding. The land is then turned into public open space, with the goal of creating coastal buffer zones that will soak up future flooding.

The program has seen surges in popularity after storms, like Hurricane Ida this past summer. But the fact that it’s a standing offer means that it also offers a response to the more mundane flooding of sea level rise.

Louisiana also runs a buyout program for three particularly flood-prone neighborhoods scattered across the state, and plans to expand to four other locations soon. In a neighborhood of Lake Charles, which was hit by two hurricanes in 2020, the buyout offers fair market value for a home, or a “resilient housing incentive” price floor. (“Fair market” home prices are linked to historical redlining, and their use has created racial bias in post-disaster recovery funding.)

“Every time it rains hard, we’ve got to leave. We do need help here,” one resident told Lake Charles’ American Press. But skyrocketing housing prices meant that the buyout didn’t cover the cost of relocation.

Correction (March 18, 2022): An earlier version of this story inaccurately described a recent report on sea level rise in the United States. It was a report led by authors from multiple federal agencies and released by NOAA, not a NOAA report.