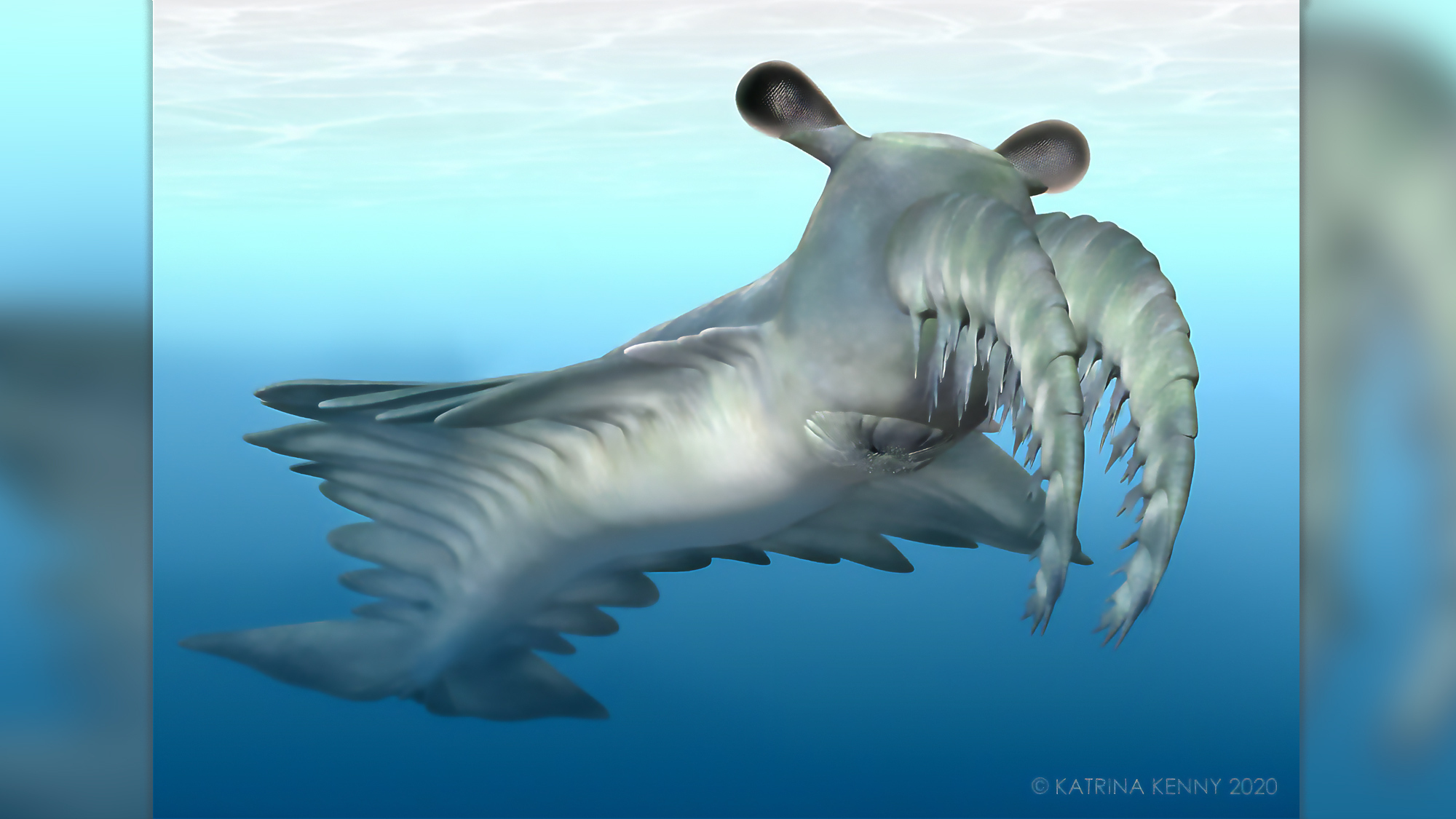

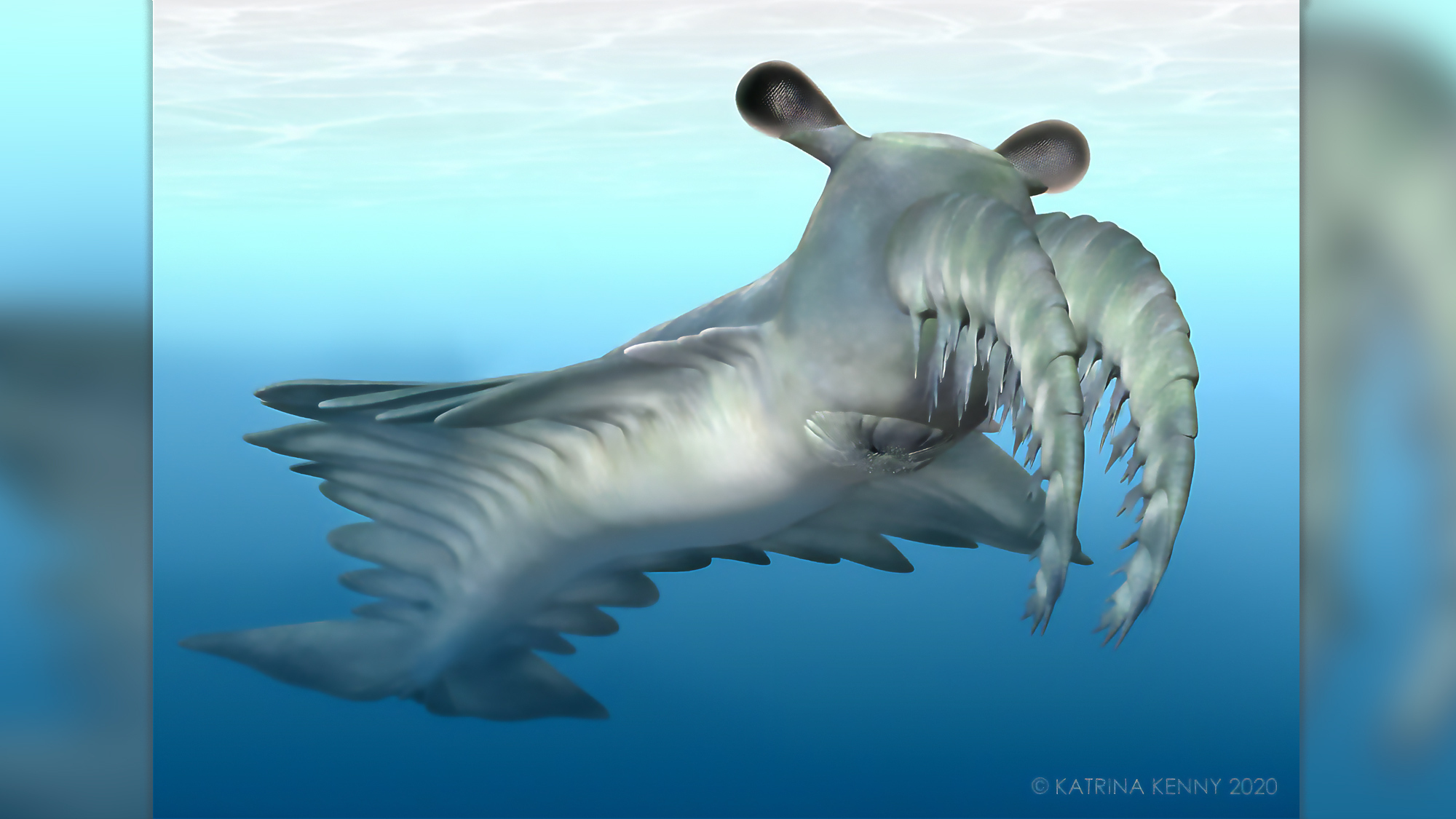

At first glance, the extinct apex predator Anomalocaris canadensis (A. canadensis) looks like it would have been a formidable foe. However, new biochemical studies on the arachnid-like front appendages on the two-foot long marine animal were likely weaker than scientists first assumed. The analysis is described in a study published July 4 in the journal Proceedings of the Royal Society B, and found that A. canadensis was possibly agile, fast, and darted after soft prey in open water instead of the harder shell creatures on the ocean floor.

[Related: This ancient ‘mothership’ used probing ‘fingers’ to scrape the ocean floor for prey.]

A. canadensis was one of the largest animals to live 541 million to 530 million years ago during the Cambrian Period. This remarkable era in the planet’s history is when numerous invertebrates and the first vertebrates (fish) appeared in the fossil record. This period of extraordinary evolution is often referred to as the Cambrian explosion due to all of the new life that emerged in the cooler temperatures and tectonic changes of the Cambrian.

Roughly translating to “weird shrimp from Canada” in Latin, A. canadensis’ was initially discovered in 1892. Since then, scientists have believed it was responsible for some of the scarred and crushed exoskeletons from trilobites that paleontologists have found in the fossil record.

“That didn’t sit right with me, because trilobites have a very strong exoskeleton, which they essentially make out of rock, while this animal would have mostly been soft and squishy,” study co-author and American Museum of Natural History invertebrate paleontologist Russell Bicknell said in a statement.

Some additional research on A. canadensis’ armor-plated, ring-shaped mouthparts lays doubt on its ability to process hard food. This new study set out to see if the predator’s long front ‘legs’ could do this instead of its mouth.

The team first built a 3D reconstruction of A. canadensis from flattened yet well-preserved fossils that have been found within Canada’s 508-million-year-old Burgess Shale. They used present-day whip scorpions and whip spiders as a comparison, and showed that A. canadensis’ segmented appendages could grab prey and also stretch out and flex.

[Related: These weird marine critters paved the way for the ‘Cambrian explosion’ of species.]

They then used a modeling technique called finite element analysis to demonstrate the stress and strain points on this grasping behavior. The researchers found that its appendages would have been damaged while grabbing onto hard prey like trilobites. Computational fluid dynamics was then used to put the 3D model of the predator into a virtual ocean current to predict what body position A. canadensis likely would have used while swimming in Cambrian seas.

This mix of biomechanical modeling techniques cast A. canadensis into a whole new light. It was probably a speedy swimmer that went after soft prey in the water with its front appendages outstretched for the grab.

“Previous conceptions were that these animals would have seen the Burgess Shale fauna as a smorgasbord, going after anything they wanted to, but we’re finding that the dynamics of the Cambrian food webs were likely much more complex than we once thought,” Bicknell said.