Throughout ancient history, giant animal versions of some of your modern favorite creatures were running wild— Madagascar’s extinct giant lemur, the ocean’s mighty megalodon, and the ground sloth are just some of many. But a salamander the size of a pygmy hippo probably wasn’t something we could’ve expected, yet the giant slippery critters ruled parts of the United States and Australia for a a solid 200 million year run on Earth.

Temnospondyls were a group of bulbous, four legged, amphibians that went extinct around 120 million years ago. They ranged from Eryops megacephalu to the aquatic Paracyclotosaurus davidi and have some similar shared features with modern salamanders, but not directly related to any living ones. In a new paper published this week in the journal Palaeontology, a team from the University of New South Wales in Sydney, Australia detail various methods of estimating the weight of these animals—not an easy feat.

[Related: Hellbender salamanders may look scary, but the real fright is extinction.]

“Estimating mass in extinct animals presents a challenge, because we can’t just weigh them like we could with a living thing,” Lachlan Hart, a paleontologist and PhD candidate in the School of Biological, Earth & Environmental Sciences said in a statement. “We only have the fossils to tell us what an animal looked like, so we often need to look at living animals to get an idea about soft tissues, such as fat and skin.”

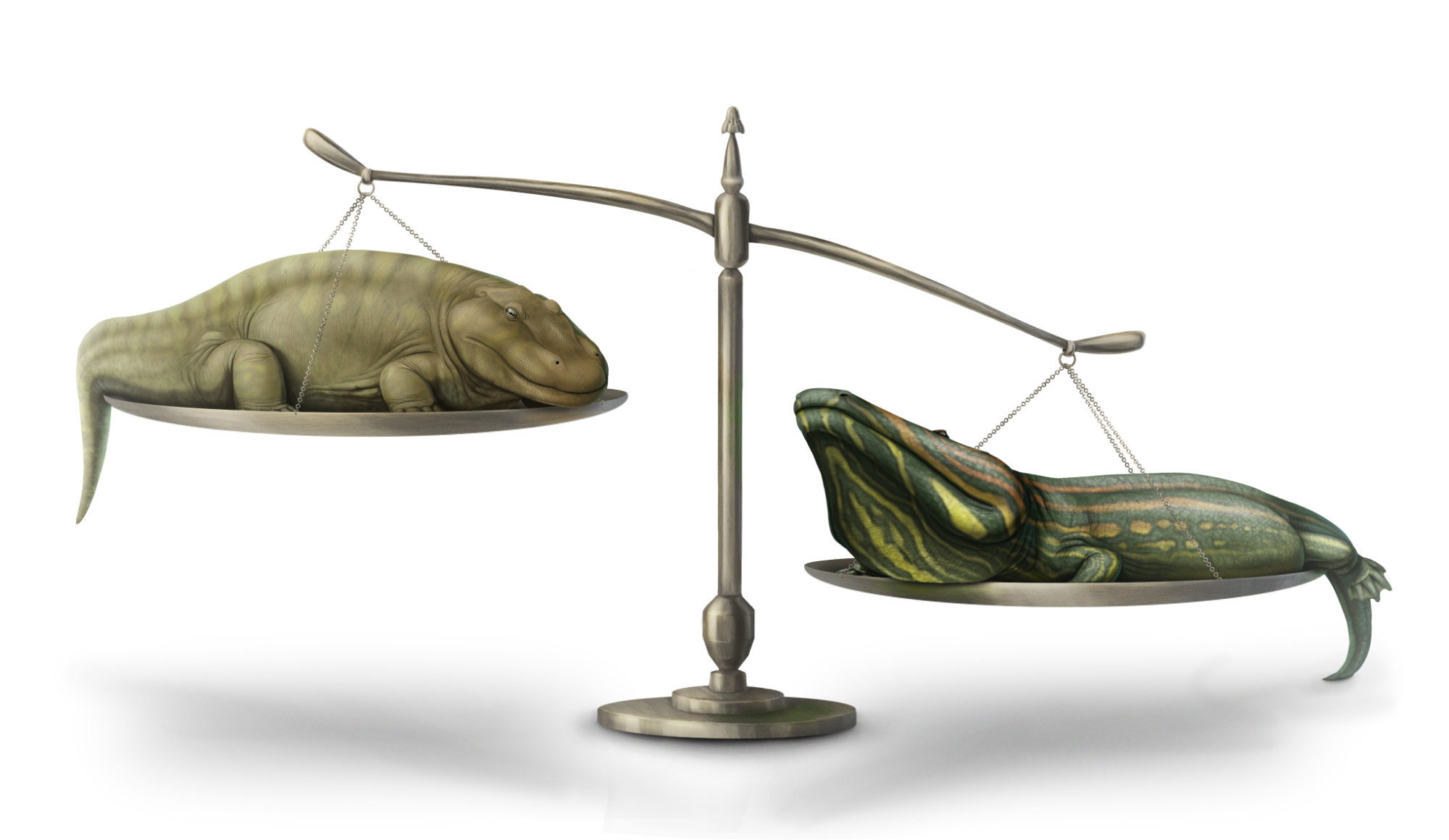

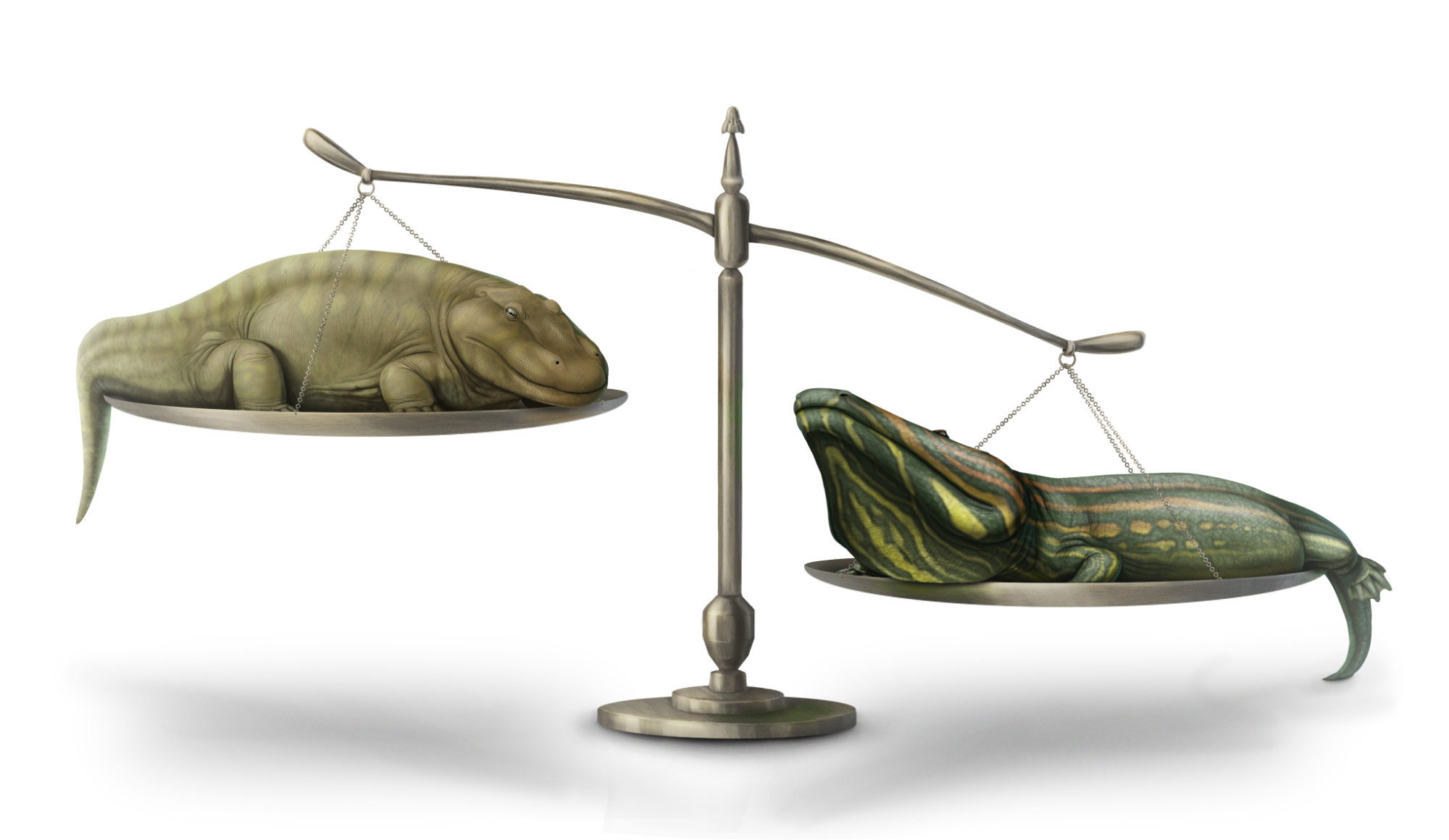

They estimate that many of the species in this group weighed close to 600 pounds, or about about as much as the pygmy hippo.

Since temnospondyls do not have any direct living relatives, the team of used five modern animals as a stand-in, including the Chinese giant salamander and the saltwater crocodile, as a way to test 19 different body mass estimation techniques. Some of the methods that provided consistently accurate body mass estimates, included using mathematical equations and digital 3D models of the animals.

“We hypothesised that as these methods are accurate for animals which lived and looked like temnospondyls, they would also be appropriate for use with temnospondyls,” said Nicolas Campione from the University of New England, Armidale, an authority on body mass estimation who was also involved in the study.

[Related: Skydiving salamanders have mastered falling with style.]

According to Hart, temnospondyls were “very strange animals,” that also grew to roughly 19 to 22 feet long. Like amphibians, they went through a tadpole stage and some of them had broad and round heads, for example Australia’s Koolasuchus, while others had heads that looked more like a crocodile. The animals in this study had the more pointy, reptilian noggins.

Some notable temnospondyls are Eryops megacephalus, which clocked in at almost six feet long and 252 pounds, and lived in the present day US and the slightly longer Paracyclotosaurus davidi from Triassic Era Australia. Paracyclotosaurus was an aquatic amphibian that tipped the scales at about The more aquatically inclined Paracyclotosaurus was the heftier of the two, tipping the scales at roughly 573 pounds.

“The size of an animal is important for many aspects of their life,” said Hart. “It impacts what they feed on, how they move and even how they handle cold temperatures. So naturally, palaeontologists are interested in calculating the body mass of extinct creatures so we can learn more about how they lived.”

According to the authors, this is the first time mass weights of temnospondyls have been studied exclusively. The team hopes that this type of knowledge can help scientists understand adaptation strategies.

“They survived two of Earth’s Big Five mass extinction events which makes them a very interesting case study on how animals adapted following these global catastrophes,” Hart said.

Correction (November 29, 2022): Temnospondyls were likely 19 to 22 feet, not meters, long.