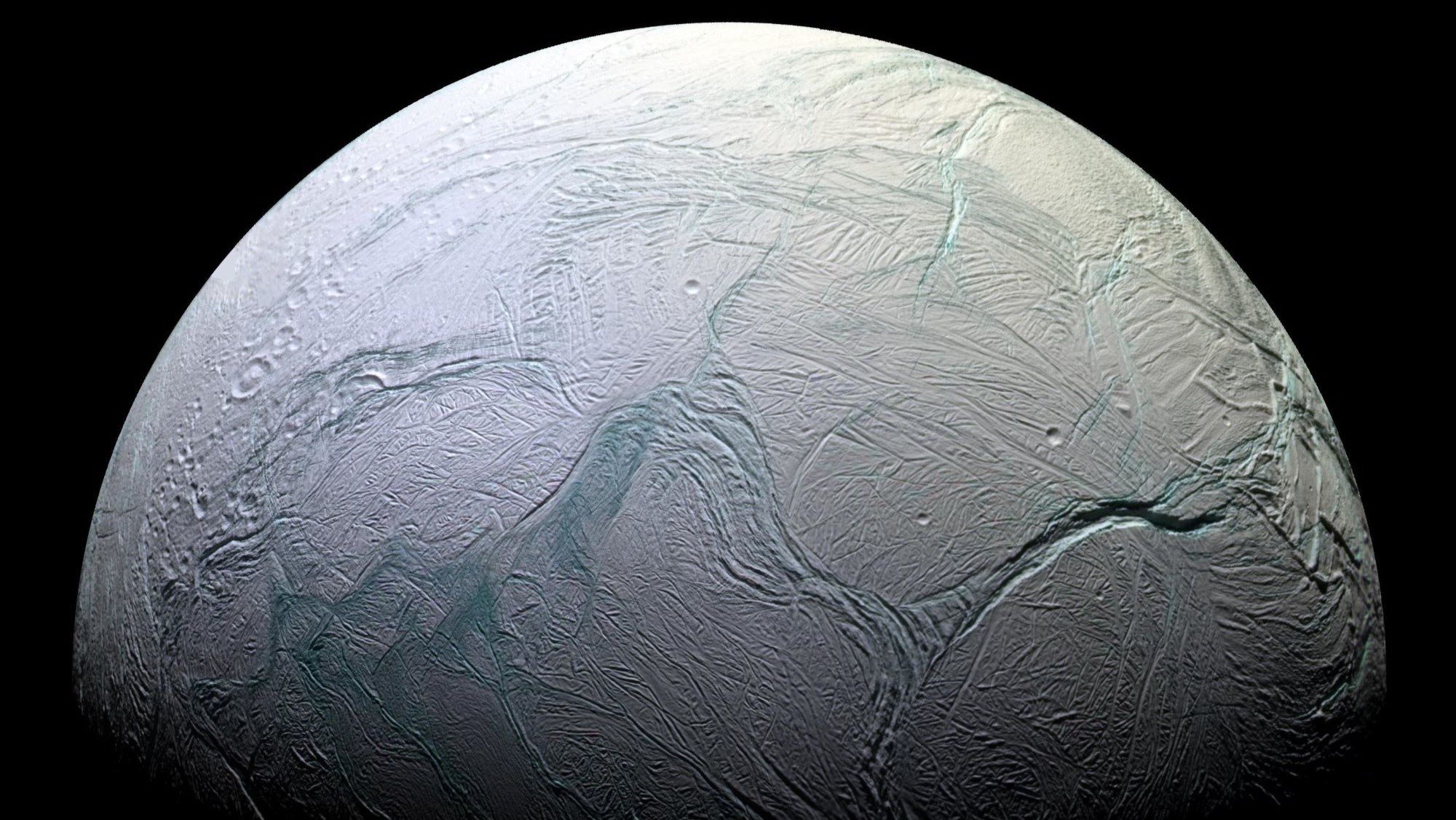

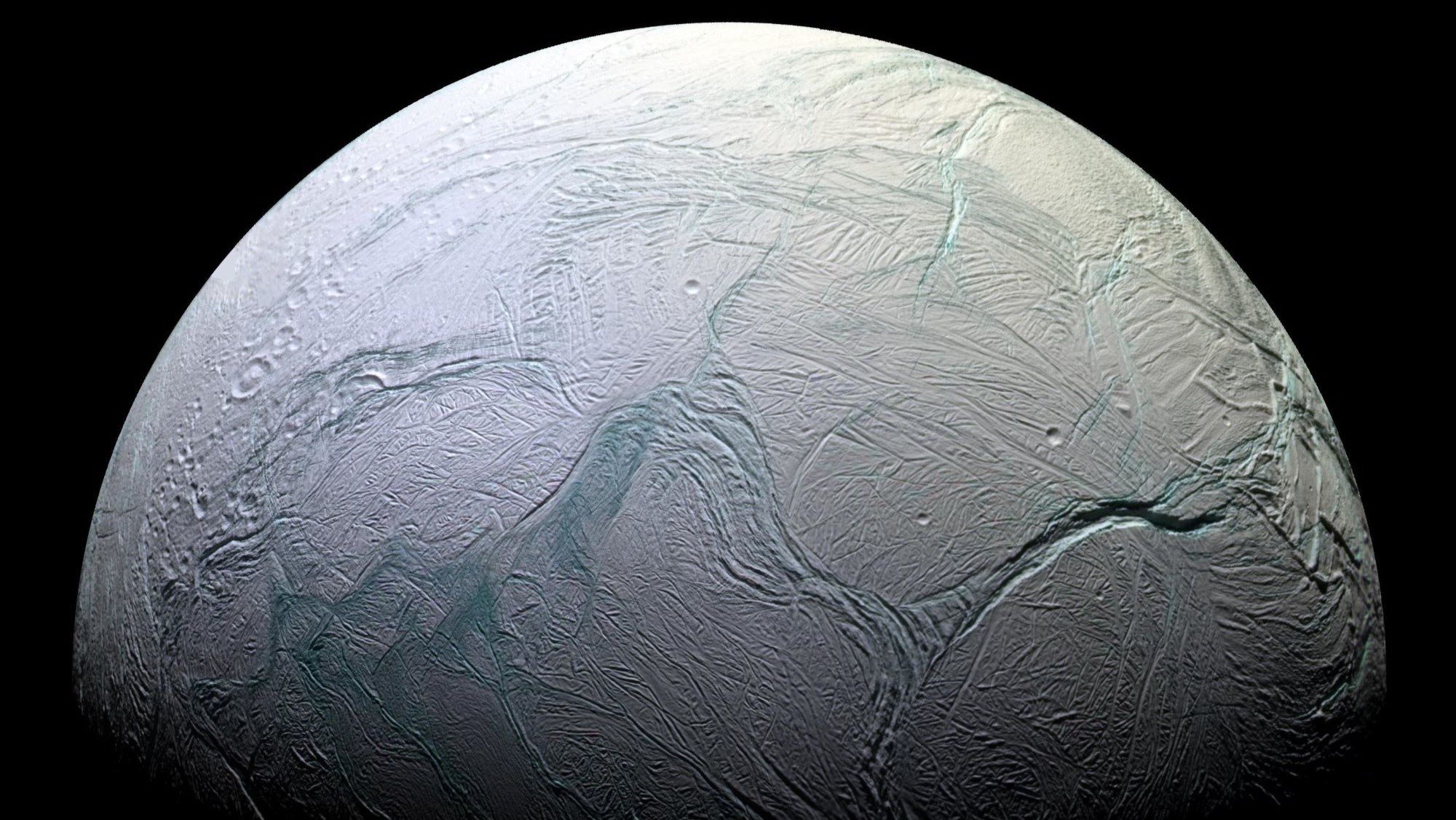

From space, Saturn’s moon Enceladus might not seem like a hospitable place for life. Its cold surface is caked thick with fresh ice, marked by craters and active cryovolcanoes that spew ice crystals. But scientists believe beneath that frozen exterior hides a salty liquid ocean. With energy from geothermal vents on the ocean floor, and a smattering of the right ingredients, it might just provide a place for life to evolve and take hold. A new analysis of data from NASA’s Cassini mission reveals that the moon has, in theory, all the chemicals it needs to support living things.

Plumes of water erupting from Enceladus contain phosphorus, according to a study published Wednesday in the journal Nature by an international team of researchers. They found the phosphorus by examining data collected by the Cassini probe from its 13-year survey of the Saturian system. It’s the first time this element—an essential component of being alive—has been found in an ocean not on Earth.

“Phosphorus in the form of phosphates is vital for all life on Earth,” says study author Frank Postberg, a planetary scientist at the Free University of Berlin. “Life as we know it would simply not exist without phosphates. And we have no reason to assume that potential life at Enceladus—if it is there—should be fundamentally different from Earth’s.”

The discovery does not provide any evidence for aliens on Enceladus. But the presence of phosphorus removes a major obstacle to any life that might evolve there. Previous studies had suggested Enceladus’s ocean might not contain any phosphorus, according to Postberg. This discovery changes how scientists must think about the moon’s potential habitability, and it may guide research on other icy moons with subsurface oceans, such as Jupiter’s moon Europa.

[Related: NASA hopes its snake robot can search for alien life on Saturn’s moon Enceladus]

Cassini was launched in 1997 and arrived at Saturn in 2004. It stayed there to study the ringed gas giant and its moons, until NASA ordered the probe to plunge into Saturn’s atmosphere to destroy itself at the end of its mission in 2017. During its mission, Cassini flew past Enceladus several times, including a 2005 flyby when the probe discovered plumes of icy material, capturing crystals that the moon had ejected. Those plumes probably represent ocean water escaping to space—planetary scientists believe that a global ocean of liquid water lies beneath the moon’s icy shell.

Researchers had looked at data from the ice grains during the Cassini mission primarily to hunt for inorganic and organic compounds, according to Postberg. But in 2017, his research team received a grant from the European Research Council to examine a larger set of Enceladus ice grain data. After four years of work, they discovered phosphorus in salt form: phosphates.

Phosphorus is one of six key elements of life as humans know it needs to exist, says Morgan Cable, an astrobiologist at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory who was not involved in the study. The other five key elements are carbon, hydrogen, nitrogen, sulfur, and oxygen. “Those elements, when you combine them in different organic molecules, they allow biochemistry, certain reactions to happen that cells need to stay alive,” Cable says.

Phosphate is particularly important because it is the backbone of the DNA molecule. It’s also a crucial component of cell membranes and of adenosine triphosphate, or ATP, which provides the energy for cellular activity. “That’s the energy-carrying molecule for all known life, the energy currency,” Cable says, an arrangement likely to be used by any life that arises on Enceladus too, though perhaps in different combinations with the other elements.

[Related: Here’s why Saturn’s ‘ocean moon’ is constantly spewing liquid into space]

Enceladus’s ocean is somewhat chemically different from Earth, according to Mikhail Zolotov, a planetary geochemist at Arizona State University and the author of a commentary on the study also published Wednesday in Nature. “In our ocean, it’s mostly table salt, like sodium chloride,” Zolotov says. On Enceladus, the salt is baking soda—the same stuff you’d find in a kitchen.

Plenty of marine Earth life could survive Enceladus’s waters just fine, according to Cable. But if any life has evolved, or ever does evolve, on the icy moon, it’s likely to be microorganisms rather than the extraterrestrial equivalent of fish or whales. That has less to do with the chemistry of the Enceladean ocean than the energy available there for life.

“On Earth the dominant energy source that all life uses, either directly or indirectly, is sunlight. You either photosynthesize directly, or you eat the plants that do it, or you eat the animals that eat the plants,” she says. Sunlight doesn’t reach the moon’s waters through its icy shell, so energy likely comes from geothermal sources—the structure of ice crystals caught by Cassini suggests the grains formed near geothermal vents on the ocean floor, where water meets a rocky interior.

“If you look at the net amount of energy that you get from that versus from sunlight, it’s orders of magnitude less,” Cable says. “That means you can either support a community of microbial cells, or you can have a handful of more energy-hungry organisms.” Enceladean whales are not entirely out of the question, but it would likely be “a lonely whale singing a sad, sad song all by itself,” she says with a laugh. “How terrible would that be?”

To know whether any kind of life exists on Enceladus will require another mission to the moon. Nothing is immediately in the works, though the influential Astrobiological Decadal Survey has recommended a flagship NASA mission to Enceladus in the next 10 years.

But two missions are heading to worlds similar to Enceladus. The European Space Agency’s Jupiter Icy Moons Explorer, or JUICE, mission launched in April and will arrive at Jupiter in 2031 to study the gas giant and its icy moons Ganymede, Callisto, and Europa. In 2024, NASA will launch the Europa Clipper mission, which should arrive at that moon by 2030. The recent findings on Enceladus give a tantalizing glimpse of what might lurk beneath those other icy surfaces: All three of the satellites are believed to contain subsurface oceans, too.