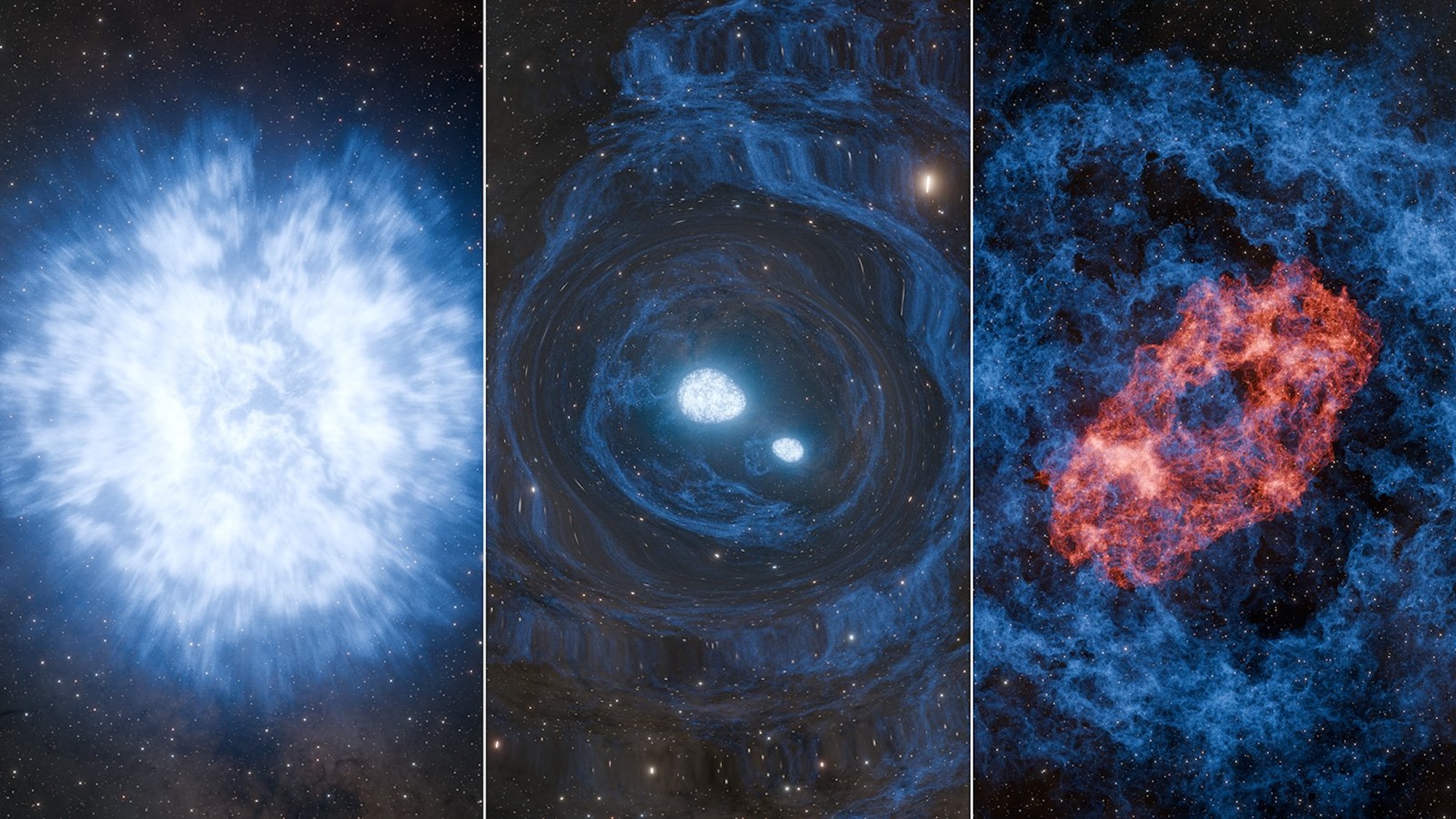

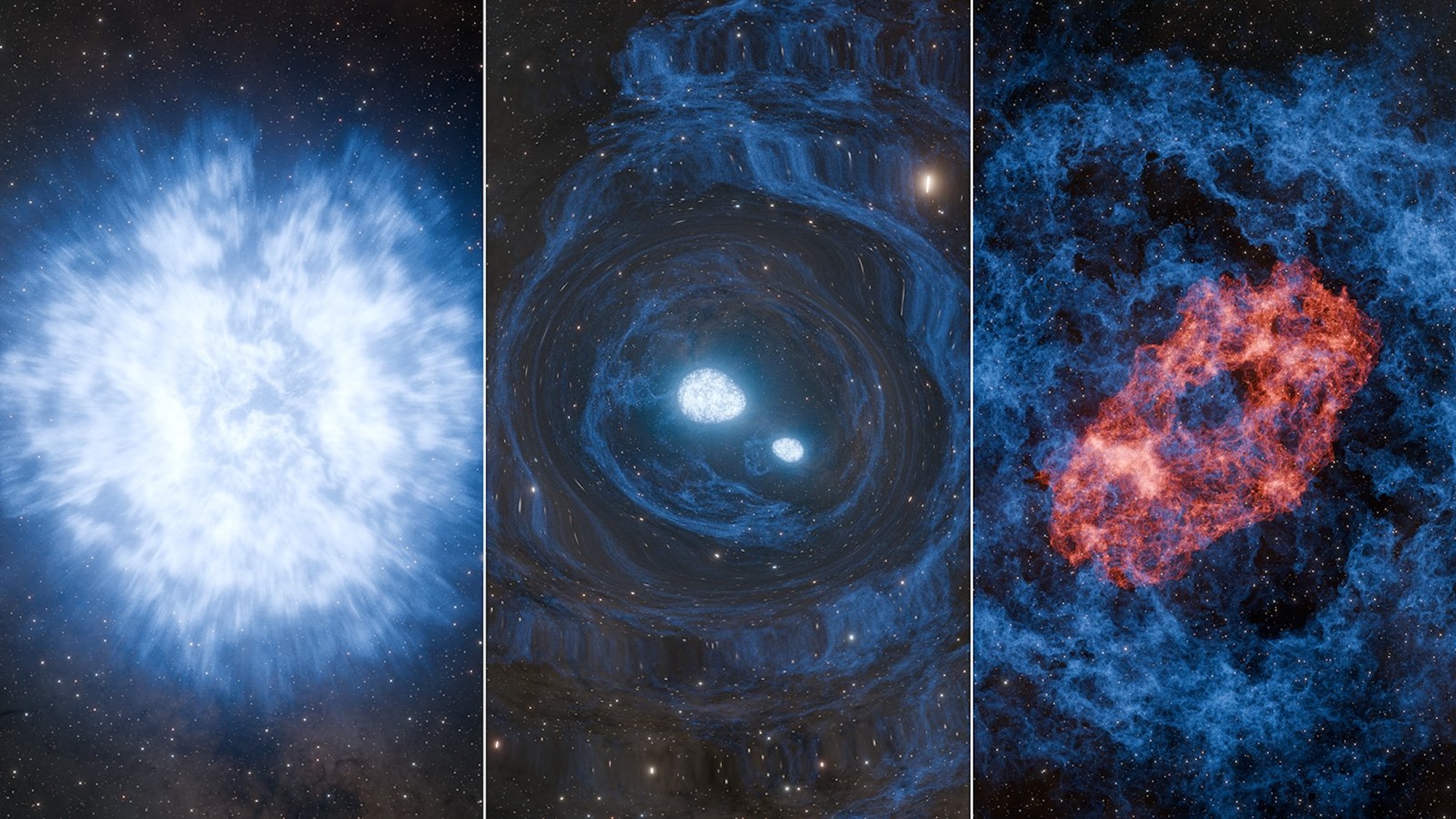

A double blast of dying stars may be the first observed case of a long-hypothesized, never proven “superkilonova.” Although astronomers are still searching for concrete answers, a study published in The Astrophysical Journal Letters may detail the historic explosion about 1.3 billion light-years from Earth.

Most of the universe’s massive stars end their lives in a blaze of glory as supernovae, but that’s not always the case. Sometimes, the end of the road is a more spectacular event known as a kilonova. These explosions are believed to generally occur after two dense neutron stars collide with one another and produce an exponentially bigger blast. While supernovae help spread heavy elements like carbon and iron across the cosmos, kilonovae create even denser remains including uranium and gold.

Astronomy’s most definitive kilonova example, GW170817, was only discovered in 2017. At the time, observational arrays like National Science Foundation’s Laser Interferometer Gravitational-wave Observatory (LIGO) and the Virgo gravitational-wave detector in Europe detected gravitational and light waves traceable back to a collision of two neutron stars. Both professional and amateur astronomers have flagged numerous possible kilonovae since then, but our understanding of these occurrences remains comparatively thin.

A team at Caltech’s Palomar Observatory think they may have another kilonova candidate, but the situation is a bit more complex. On August 18, 2025, both LIGO and Virgo detected gravitational wave signals, setting off an alert system for the global astronomical community. Researchers at the Palomar Observatory’s Zwicky Transient Facility soon identified a quickly fading red body about 1.3 billion light-years away. Later classified AT2025ulz, the object displayed similar, fading red wavelengths as GW170817.

“At first, for about three days, the eruption looked just like the first kilonova in 2017,” Palomar Observatory director and study co-author Mansi Kasliwal said in a statement.

However, AT2025ulz began to brighten again a few days later, this time turning blue to indicate the presence of hydrogen. For many, this proved the blast wasn’t another rumored kilonova, but a regular supernova.

Kasliwal suspected something else was at play. The cumulative data on AT2025ulz admittedly did not resemble the kilonova GW170817, but it also didn’t align with a classic supernova. Furthermore, the gravitational waves suggested at least one of the two neutron stars was less massive than the sun. Neutron stars are inherently small—only about 15 miles wide—and range in mass from 1.2 to three times our sun.

How could a neutron star be even smaller? Kasliwal’s team offered two possible explanations. In the first scenario, a quickly spinning star goes supernova before fissioning into two, sub-solar neutron stars. A second theory involves the same beginning as a supernova, but instead of fission a disk of debris starts forming around the collapsing star. This material eventually combines into a small neutron star, much like the formation process of early planets.

Given the possible sub-solar neutron star implied by the gravitational wave data, researchers hypothesize that a supernova’s two newborn neutron stars orbited into one another to generate a separate kilonova. This could explain the early red wavelengths, since kilonovas generate red spectrum heavy metals. As the supernova expanded, its blue spectrum waves eventually obscured the kilonova.

“The only way theorists have come up with to birth sub-solar neutron stars is during the collapse of a very rapidly spinning star,” added Columbia University astronomer and study co-author Brian Metzger. “If these ‘forbidden’ stars pair up and merge by emitting gravitational waves, it is possible that such an event would be accompanied by a supernova rather than be seen as a bare kilonova.”

Metzger, Kasliwal, and their colleagues stress that their theory remains just that—a theory. Still, the possibility is intriguing enough to continue the search for additional candidates in the hopes of unequivocally identifying a superkilonova. Until then, Kasliwal explained the importance of continuing to study possible suspects, even if they start to look like a regular supernova.

“Everybody was intensely trying to observe and analyze it, but then it started to look more like a supernova, and some astronomers lost interest,” she said. “Not us.”