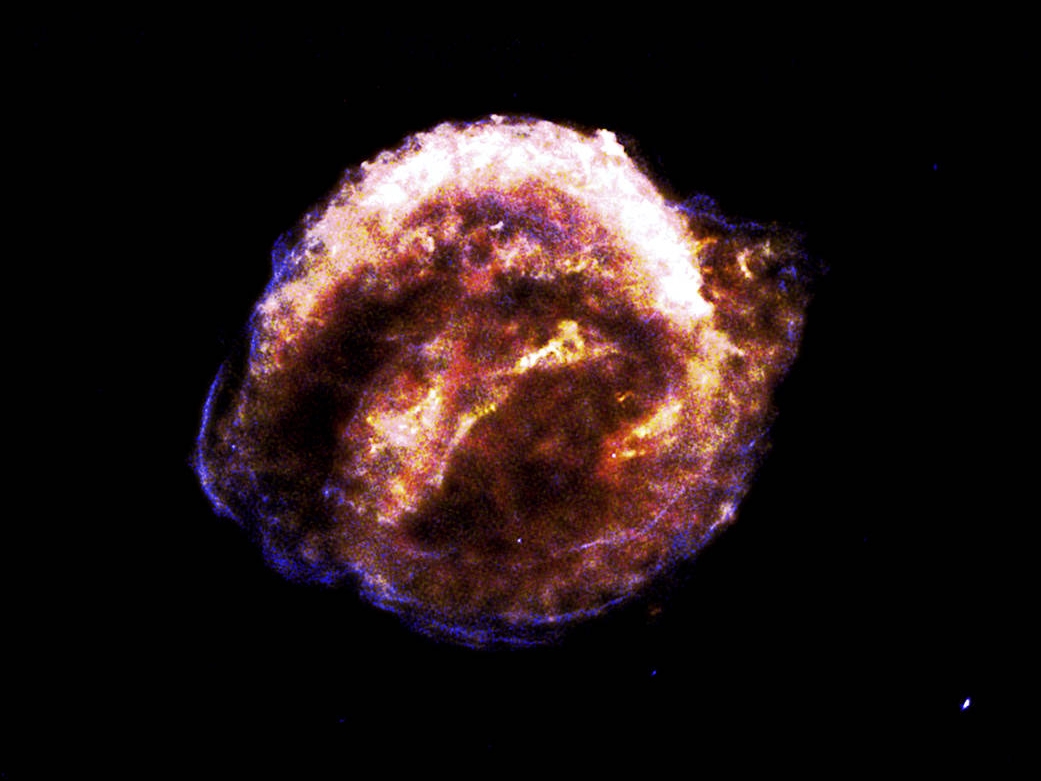

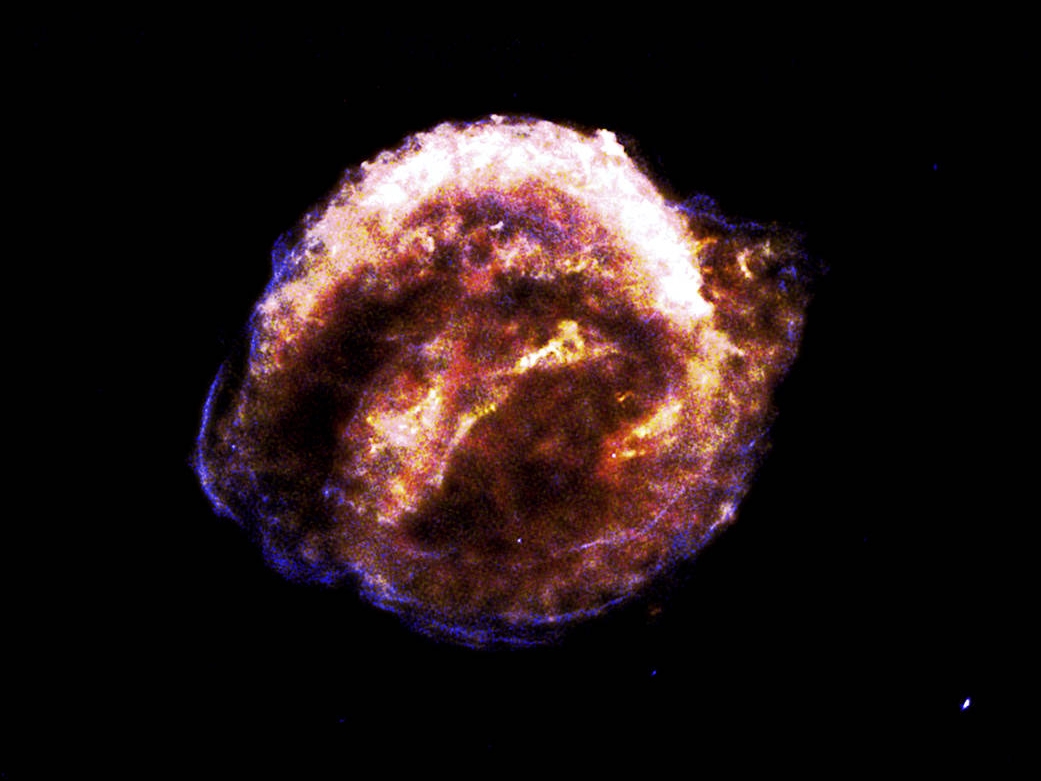

On July 4, 1054, a star in the constellation Taurus exploded. Some 6,500 light years away, the inhabitants of a canyon in what would, centuries later, be known as New Mexico took notice. They painted the celestial fireworks—which likely outshone Venus—on the sheltered face of an overhanging cliff. Detailed Chinese records of the “guest star” suggest it was visible during the day for more than three weeks, and at night for nearly two years.

Astronomers estimate that perhaps 50 stars have exploded in our galaxy during the last millennium—one roughly every two decades. But the 1054 supernova is one of just five stellar detonations that researchers have confidently identified in historical records, the last of which took place more than 400 years ago. So where are all the supernovae? Where are our celestial fireworks?

Intrigued by this discrepancy, a team of astronomers recently explored how hard it is to spot supernovae and where in the sky they are most likely to be seen. In a not-yet-peer reviewed preprint published Monday on the arXiv, they announced an odd result. While the overall number of supernovae checks out, they’re in all the wrong places.

“I was just stunned,” says Brian Fields, a University of Illinois astronomer and coauthor of the study. “All of the confident [supernovae] completely avoided where the model said they’d be.”

The group, which included undergraduate researchers Tanner Murphey and Jacob Hogan, started with work from other researchers analyzing where in the Milky Way supernovae are most likely to take place. They treated the galaxy as something like two fried eggs stacked yolk-side out; it has a flat disk (which we see edge-on, as a river of stars spilling across the sky) with a round bulge in the middle. Supernovae should be more common in the center where stars, especially swollen red giants just about ready to pop, crowd thickly together. Such calculations have previously suggested that a star dies, somewhere in the bulge or disk, every few decades.

But not all explosions catch the attention of stargazers. Dust expelled from previous generations of stars makes the whole galaxy—and especially the center—look hazy, and supernovae on the other side of the disk might be hard to see from Earth. And to enter the historical record, a supernova has to be not just visible but, as Fields puts it, go-and-tell-the-Emperor-visible. The team estimated that perhaps just one of five supernovae blazes brightly enough to burn through the dusty haze and shine for 90 days, meaning that one might expect such a dramatic event once every century or two—about what historical records indicate.

The end result was a map showing where in the sky the brightest supernovae are most likely to occur, and it was not a complicated map. It roughly traced the locations of some 300 instances of splattered star guts known to astronomers, clustering in the galactic disk and especially near the center of the Milky Way.

But that’s not where historical astronomers saw their transient stars, which exploded above and below the disk. The supernova in 1054, notably, left a debris cloud in precisely the opposite direction—behind us, away from the galactic center. “That’s the most disfavored place in our model and that’s where the most famous supernova is,” Fields says. “That’s amazing to me.”

With only a handful of recorded events, the group can’t make strong statistical claims. But they suspect that the peculiar locations of the historical supernovae undermine one or more of their assumptions. Treating the Milky Way as two fried eggs isn’t the most sophisticated model, for instance. It neglects the clumping of stars into spiral arms, which the group hopes to consider in future research.

The team’s results also highlight a gap in the historical record. All accounts come from civilizations in the northern hemisphere, even though stargazers in South America, Africa, and Australia had a clearer view of the galactic disk—a front row seat to stellar explosions. Perhaps Incan depictions of the 1054 supernova and other events lie buried in the Peruvian Amazon.

Bradley Schaefer, an astronomer at Louisiana State University who was not involved in the research, said in an email that the group had done good work and created a believable sky map that matches previous results. The funky locations of the five historical supernovae don’t worry him too much though, given their low number and the lack of known records from the southern hemisphere.

Much of the interest in this historical astronomy lies in understanding how ancient cultures thought about the stars, but old data sets can also lead to new science. Many sites of stellar wreckage still smolder as expanding clouds, and pinpointing their year or even day of origin can help astronomers reconstruct their history, Fields says.

Researchers also ponder the past to prepare for the future. When the next Milky Way supernova goes off—whether it’s in a year or a century—astronomers definitely won’t miss it. Neutrino detectors noticed a supernova in a neighboring galaxy in 1987, and if something similar happened in our cosmic backyard, Fields says, they would light up “like a Christmas tree.”

Today’s researchers might not bother sif a local star exploded, but they would quickly notify each other, coordinating observations of neutrinos, gravitational waves, and a wide range of wavelengths of light to turn even a dim burst into the best understood supernova in human history.

And there’s a good chance we could see it with the naked eye too. A brilliant and lingering supernova may be a once-in-a-few-centuries occurrence, but we’ll have astronomers and the internet to guide our eyes toward a fainter dot. Perhaps half of all supernovae could be just barely visible, Fields estimates in the new work, if you know where to look. And one of those could come along any day now.

“It’d be really phenomenal to have a galactic supernova,” he says. “You just have to wait, and it will more or less come out of the blue.”