WHEN ENGLISH PLAYWRIGHT William Congreve wrote, “Music hath charms to soothe a savage breast” in his 1697 tragedy The Mourning Bride, any real efforts to measure how nonhuman animals produce and perceive music—what we now call zoomusicology—were far in the future.

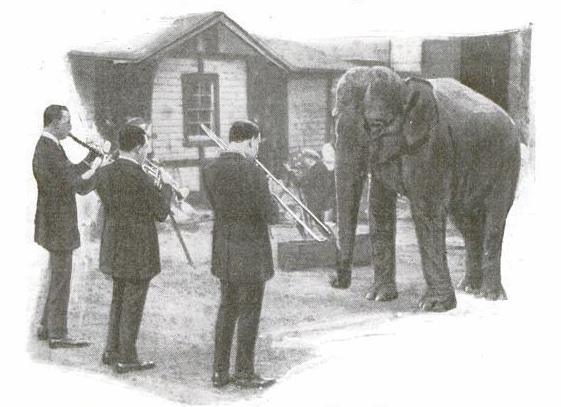

Early 20th-century attempts to test the oft-misquoted quip (“beast” rather than “breast”) appeared to prove it quite wrong. In July 1921, Popular Science covered one such interlude at New York City’s Central Park Menagerie—now known as the Zoo. “The polar bear exhibited astonishment,” and a small tame wolf “ran wildly around, panic-stricken.” The elephant stood out, seeming oddly unfazed.

The purpose of the demonstration, according to an account in The New York Times, was “to gauge more or less scientifically the effect of jungle music on animals.” (“Jungle music” being a racist epithet for 1920s jazz, which was commonly associated with Black performers and progressive counterculture.) “There were some sketchy theories about animal songs and music back then,” says Emily Doolittle (no relation), a composer and zoomusicologist specializing in songbirds.

Scientists ranging from neurologists to veterinarians have since dug into figuring out which tunes our furry, feathered, and flippered pals do—or don’t—want to hear. In 1996, when a team at the Southwest Foundation for Biomedical Research played the radio for baboons, their heart rates slowed. One 2004 study published in Brain Research showed that listening to Mozart reduced systolic blood pressure by 15 percent in some rodents. And in 2008, a music theorist played clarinet for a humpback whale who seemed to change its own tune in response. Doolittle points out that songbirds experience a surge of happy-making chemicals like dopamine when they chirp at dawn.

Acclaimed cellist David Teie, a zoomusicologist whose compositions cater to cats, monkeys, dogs, horses, and (sure) humans, opts to mimic the sounds creatures themselves make when they’re feeling chill and safe. His soothing kitty melodies, for instance, reproduce the time signature of feline heart rhythms and the tones of mama cats’ purrs.

As for 1921’s indifferent Central Park elephant? A 2015 violin performance at the Pairi Daiza Zoo in Belgium managed to charm resident pachyderms, who swayed their trunks. But, Doolittle cautions, without more data to back it up, we shouldn’t take that to mean elephants prefer classical to jazz.

This story originally ran in the Spring 2021 Calm issue of PopSci. Read more PopSci+ stories.