Researchers at UCLA have done something they didn’t think was possible: without the use of surgery, they helped people with severe paralysis voluntarily move their legs — something that’s never been accomplished before. While it may be years before this new approach could be widely used, the researchers now think patients with severe spinal cord injuries may be able to recover multiple body functions, which could greatly improve their quality of life. The research was published yesterday in the Journal of Neurotrauma.

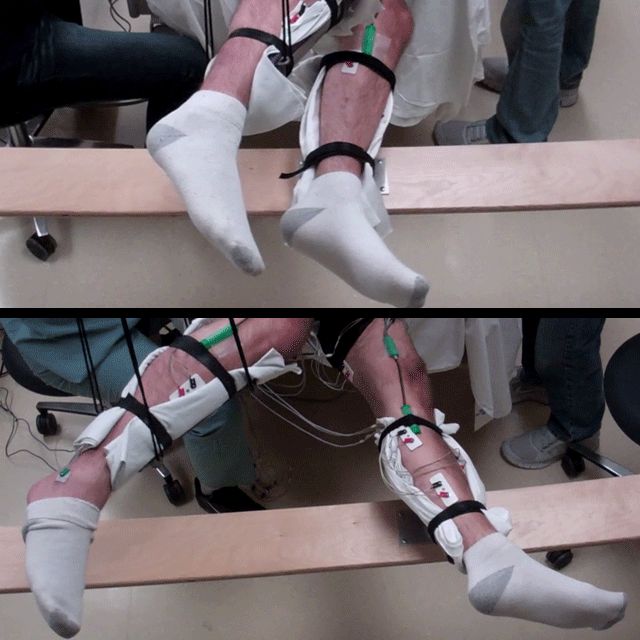

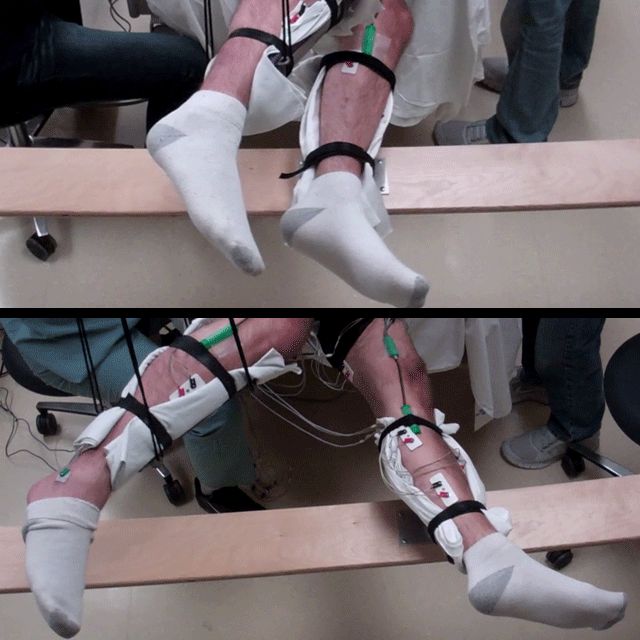

The video below shows one patient’s movement before and after treatment.

Over the past few years, researchers have been looking for ways to stimulate muscle movement in paralyzed patients. Last year, V. Reggie Edgerton, the lead author of this study, used epidural electrical stimulation to help paralyzed patients move their legs, hips, ankles, and toes. However that procedure requires a surgically implanted device to work.

Earlier this year, Edgerton and another group of researchers were able to allow partially paralyzed patients to move their legs on their own using a new treatment that didn’t require a surgical implant. Seeing this, Edgerton eagerly tried out a similar approach on patients with severe paralysis.

The study was extremely small, only five patients were tested. However, Edgerton believes the results may lead to major advances for the 6 million Americans who live with paralysis and the almost 1.3 million who have spinal cord injuries.

“The potential to offer a life-changing therapy to patients without requiring surgery would be a major advance; it could greatly expand the number of individuals who might benefit from spinal stimulation,” said Roderic Pettigrew, director of the National Institute of Biomedical Imaging and Bioengineering, the organization that funded the study, in the UCLA press release.

For the study, Edgerton and his team used a technique called transcutaneous spinal cord stimulation where they placed electrodes on a patient’s lower back and sent a unique pattern of electrical currents through the electrodes. The patients’ legs were held up by braces that hung from the ceiling. After a few sessions, the patients were able to voluntarily extend their legs during the stimulation. To increase this movement, the researchers gave them a drug called buspirone, which had been found to induce leg movement in mice with spinal cord injuries, during the final four weeks of the study.

By the end of the study, all five patients, while on the drug, were able to voluntarily move their legs without needing stimulation. Edgerton thinks they were able to achieve this so quickly because the stimulation had “reawakened” dormant, but functioning, neural connections.

According to the press release, Edgerton thinks this new approach could be more accessible to patients as it doesn’t require surgery and it’s likely to cost one-tenth the amount that the current surgical procedure costs. In the future, Edgerton hopes to use this approach on people who have severe, but not complete paralysis as they think that set of patients is likely to improve even more from this treatment.