On April 19, the Biden administration restored a critical climate provision to a bedrock federal environmental law, the National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA) which had been narrowed under former President Donald Trump. The standard will require new infrastructure projects to more broadly consider how they alter the environment, especially when they are planned near already polluted communities.

That recently revived rule is one of several recent White House policies to address climate change by pressing federal and corporate decisionmakers to fully reckon with the costs of an overheated planet.

[Related: The US government could be net-zero by 2050]

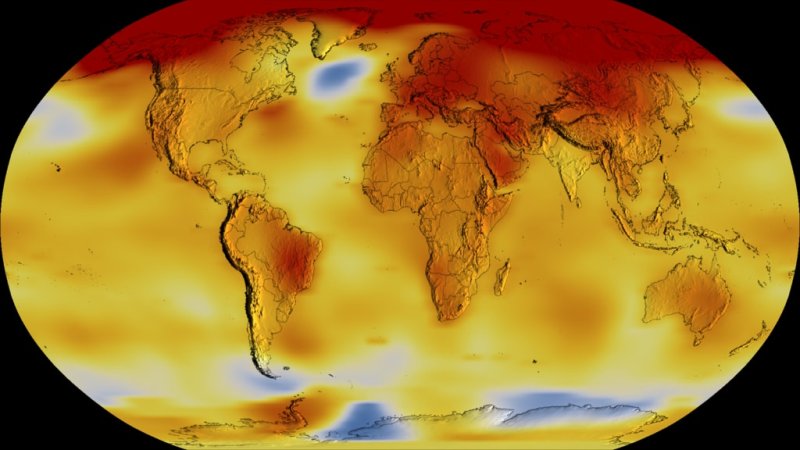

The price of climate change is hard to fathom—financial consulting firm Deloitte predicts that the US stands to lose $14.5 trillion over 50 years if the planet warms by 3°C degrees Celsius—but policymakers have been slow to simply incorporate any of those risks into cost-benefit analyses. The policies all face legal opposition from a range of fossil fuel companies, states, and construction industries.

A more forward-looking NEPA

When major projects apply for federal permits, from the construction of a dam or highway or pipeline, NEPA requires the permitting agency to conduct an environmental analysis. In the new rule, those analyses will need to consider wider impacts, from carbon emissions to wildlife habitats. In 2020, the Trump administration restricted the reach of NEPA analyses to only “reasonably foreseeable” effects, like draining wetland or construction pollution. The key change expands NEPA analyses to other environmental factors, including “indirect effects,” such as the particulate pollution and carbon emissions produced by a new freeway.

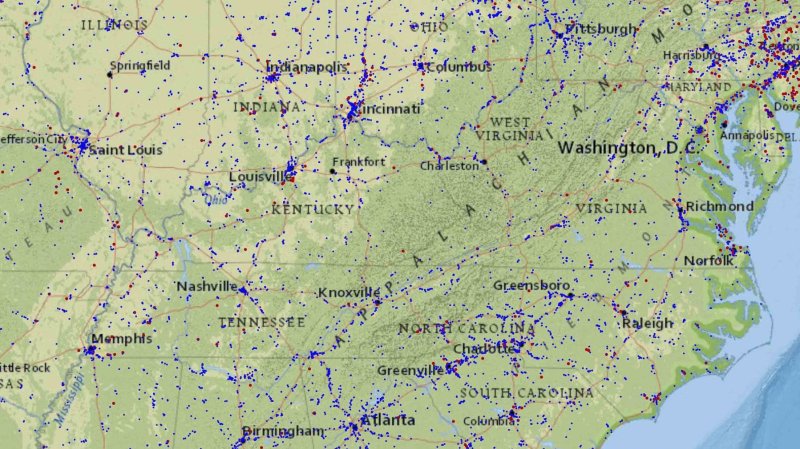

The new rule will also require analyses to consider “cumulative effects” on communities. In practice, this means that projects in places already exposed to air and water pollution may face more careful scrutiny—part of the Biden administration’s attempt to build environmental justice into its climate and environment policies.

According to The New York Times, White House officials say that the Biden administration has already weighed these climate effects in its environmental analyses, so not much would change in the near future. But the rule—if it survives almost inevitable legal challenges—would create a consistent process for future administrations to track the environmental impact of federal projects.

Putting a price tag on carbon

The broader effect of some of these new environmental policies is to push government agencies and publicly traded companies to account for the costs of carbon.

The first such change took place immediately after Biden’s inauguration: The administration reinstated an Obama-era plan that directed federal agencies to account for the social cost of carbon. That price on carbon, $51 per ton, reflects the global cost of climate change, including flood damage, crop loss, and the spread of infectious diseases.

That price of carbon is used in cost-benefit analyses, which may happen alongside or outside of a NEPA review to approve federal projects and policies. Decisions that increase carbon emissions will be judged as having higher financial costs, and are therefore less likely to move forward.

[Related: Companies may soon pay a higher price for emitting carbon. But will it be high enough?]

A group of oil- and gas-producing states, led by Louisiana, sued over the carbon-price rule, and federal courts have issued mixed rulings on the president’s authority to set a carbon cost. It remains in place as states ask for Supreme Court review. The legal maneuvering has delayed oil and gas lease sales as well as federal energy efficiency and mass transit grants, according to the Wall Street Journal.

Environmental transparency on Wall Street

Meanwhile, in March of 2022, the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC), which regulates publicly traded companies, added a climate disclosure requirement for major firms. SEC-regulated companies already needed to publish regular information on profits and debts, with the aim of protecting shareholders and investors from fraud. Now, companies will also need to make public how they contribute to climate change and tell investors what risks they’re accounting for.

In the case of big tech firms like Facebook and Google, such risks might include the fact that their headquarters are in danger of sinking into the San Francisco Bay. Those companies will also need to gather data on the emissions produced as they conduct business, like the power used to run a data center. In some cases, they’ll also have to collect data on the emissions their customers produce, like when Amazon Web Services provides cloud technology for oilfields.

None of these policies directly reduce emissions. They don’t mandate the closure of specific power plants, or create investments in heat pump manufacturing—goals that have been shelved with the failure of the Build Back Better package in Congress. But they do force the American government and businesses to confront the massive costs of climate change, rather than leaving them for the future.