Fusing horrifying real-world experience with science and popular fiction, author Richard Schweid presents the lowly cockroach in all its trash-eating, ultimate survivalist splendor. In a companion Q+A with Nexus Media, Schweid gives his take on how the bugs will navigate a warming planet. In the excerpt below, Schweid shares some of his own experiences with roaches, Chapter 1 of The Cockroach Papers: A Compendium of History and Lore from the University of Chicago Press.

Saving All Sentient Beings

In the summer of 1967, I was twenty-one years old and living in New York City. I had fled from a long childhood and adolescence in Nashville. I slept in the living room of a small, three-room apartment on the second floor of a Christopher Street brick building, half a block west of Sheridan Square. This place had a narrow metal shower built into a corner of the bedroom and the toilet was in a closet off the living room. The woman who paid the rent did so out of a monthly allowance from her family, and she was sleeping with a friend of mine. He moved in and brought a pair of friends with him, one of whom was myself. She was an open and generous soul, so the living arrangements were fine with her.

There was a sofa in the small living room, and the two of us slept out there. I put the cushions on the floor night after night, month after month, and my friend Jeff did his best to make himself comfortable on the sprung springs of the sofa. Every so often, when we ran smack-dab out of cash, we would walk over to the pier on the Hudson River where ships docked with boxes of produce. A large group of men gathered each evening for a shape-up, which meant standing around in a loose cluster inside a hulking, high-ceilinged wooden warehouse, waiting to see who the foreman would choose to give work to that night. The work entailed loading boxes of fruit and vegetables on to trucks, packing them inside tractor trailers to be hauled across the country. Five dollars an hour, cash at the end of the night.

Work was not a high priority. A half dozen of us spent our time hanging out, drinking cheap wine, smoking good weed, playing music, writing long collective stories, painting together, trying to put rhyme or reason to our lives and the world around us; we were determined to save not only our own asses but those of our friends, neighbors, and every sentient being in that order from the tyranny of history repeating itself, history as dull labor, war, and death. I was usually tired enough and sufficiently substance-saturated by the time everyone else had left or gone to bed, and Jeff and I could dismantle the sofa, that I went right to sleep on the cushions, despite the cracks between them and the narrowness of the platform they provided.

I slept in a T-shirt and underwear, pants and shirt tossed on a chair. There was a particular July morning when I left my dreams behind and woke up, and my first thought, even before opening my eyes was, What a strange feeling: the lightest of ticklings all over my body, as if someone were breathing very gently up and down my stretched-out form. Tiny gusts of air barely ruffling the hairs on my arms and legs. Lazily, I opened my eyes. The evening before, while I had been loading fruit, exterminators had come by and fumigated the building. My supine body was a charnel house, a killing field of dead and dying roaches that had come out from behind the walls, from the dark spaces under the refrigerator and the stove, from all their sanctuaries. They were driven out in confusion as their poisoned bodies broke down, and their nervous systems went haywire. They died slowly, on their backs, legs kicking feebly into the air. The spasmodically jerking legs are what I had felt upon awakening. The roaches covered the floor, thousands of them, and they were dying all over me. I leapt up screaming, my shout open throated and horrified, as if the cushions had suddenly become a bed of hot coals.

I spent many months of my life sleeping on the floor of that apartment, walking through the neighborhood, east to Greenwich Village, west to the Hudson River. I spent hours and days sitting on the stoop watching the weird world of the West Village go past. I was convinced that this was my life, and a worthy one at that, a conviction I can barely remember now. I can vaguely recall how it felt to feel that way, so certain then that so much idle time would bear fruit further down the road, but now all the days of those years are reduced to nothing but a black hole with shards of recollections scattered here and there, bits of colored cloth caught on the jagged edges of what passes for my memory. But one thing I remember as if it happened yesterday was how those roaches felt dying all over my body.

In the store the old men gathered, occupying for endless hours the creaking milkcases, speaking slowly and with conviction upon matters of profound inconsequence, eying the dull red bulb of the stove with their watery vision….In the glass cases roaches scuttled, a dry rattling sound as they traversed the candy in broken ranks, scaled the glass with licoriced feet, their segmented bellies yellow and flat.

from The Orchard Keeper by Cormac McCarthy

After a while, the shape-up work loading fruit became kind of discouraging. Some nights there wasn’t work, and as the fall evenings grew chillier, it was a cold walk over to the pier, so I looked around for something a little steadier. Waiting on tables seemed like a good idea and I started to walk around the neighborhood, asking. The first waiter’s job I landed was at a coffee shop that occupied a corner of Sixth Avenue and West Fourth Street. My debut night on the job, the cook told me to go down in the basement and bring up a sack of potatoes. He was a corpulent black man with strong arms, biceps the size of hams, and a round, bowling-ball head shaved bare. “The light’s at the top of the stairs,” he said, motioning toward the door to the basement.

I flicked on the switch, and the light illuminated a busy traffic of roaches and rats moving rapidly across the floor at the bottom of the stairs. Lots of animals dine on roaches, including cats, lizards, and monkeys, but they seem to be well out of harm’s way in the company of rats, at least where other food is being stored. I was halfway down the stairs before my mind registered what my eyes were seeing and my ears were hearing: the scurrying of a healthy population of both rats and roaches. I turned around and tore back upstairs to bear news of the infestation, shouting, “There’s a bunch of roaches and rats downstairs,” wondering if the restaurant would have to be closed down while the exterminators were called in to eliminate this obviously state-of-emergency threat to public health.

The cook couldn’t stop laughing, even after he’d called in all the rest of the restaurant’s staff to tell them how I’d come running back up the stairs yelling that the basement was full of roaches and rats. He laughed until he was wiping away tears with his big white apron, asking, “Where you from anyway, boy? Where you from?” Then he sent me back down for the potatoes.

Out of the corner of his eye he saw Umbrella Man scoop a roach off the bar in a movement surprisingly swift for one so sluggish—and in the same movement jam it between his teeth. Frankie’s hand stopped on the glass: here came Umbrella Man, the bug’s blood streaking down teeth and chin and the bug itself crushed-feelers still waving between the teeth—”Man! Wash! Gimme wash!”—pleading between the clenched teeth and his smeared face right up to Frankie’s.

Frankie turned his head away, shoved the beer toward Umbrellas and didn’t turn his head back till he heard Umbrellas drain the glass to the last drop.

“He never done anything like that before,” Frankie complained to the widow Wieczorek. “What’s gettin’ into him?”

“He does it all the time now,” Widow explained with a certain pride; as if she had taught him such a trick.

from The Man With the Golden Arm by Nelson Algren

Algren was practically impeccable. Not only was he the hardest punching writer in the United States, as his contemporary Ernest Hemingway said after this book was published, but he was a master at combining humor and human horror, the urban novel at its best. A graveyard humor born of tenements, taverns, and neighborhoods, the low-grade, ongoing scuffle to survive, and unlike so many fighters who grow old, his punch never slowed down, his sense of timing never dulled. His penultimate book of fiction, a collection of short stories called The Last Carousel, published in 1973, is Algren at the top of his form.

He uncharacteristically got a detail wrong in the above passage from his most famous novel, originally published in 1949 and winner of the first National Book Award. Cockroach blood is a pigmentless, clear substance circulating through the interior of its body, and what usually spurts out of a roach when its hard, outer shell—its exoskeleton—is penetrated or squashed is a cream-colored substance resembling nothing so much as pus or smegma. Not the dark liquid implied in Algren’s evocative description of a repulsive way to cadge a beer, a sequence that, unsurprisingly, was entirely left out of Otto Preminger’s watered-down film of the novel, which starred a young Frank Sinatra.

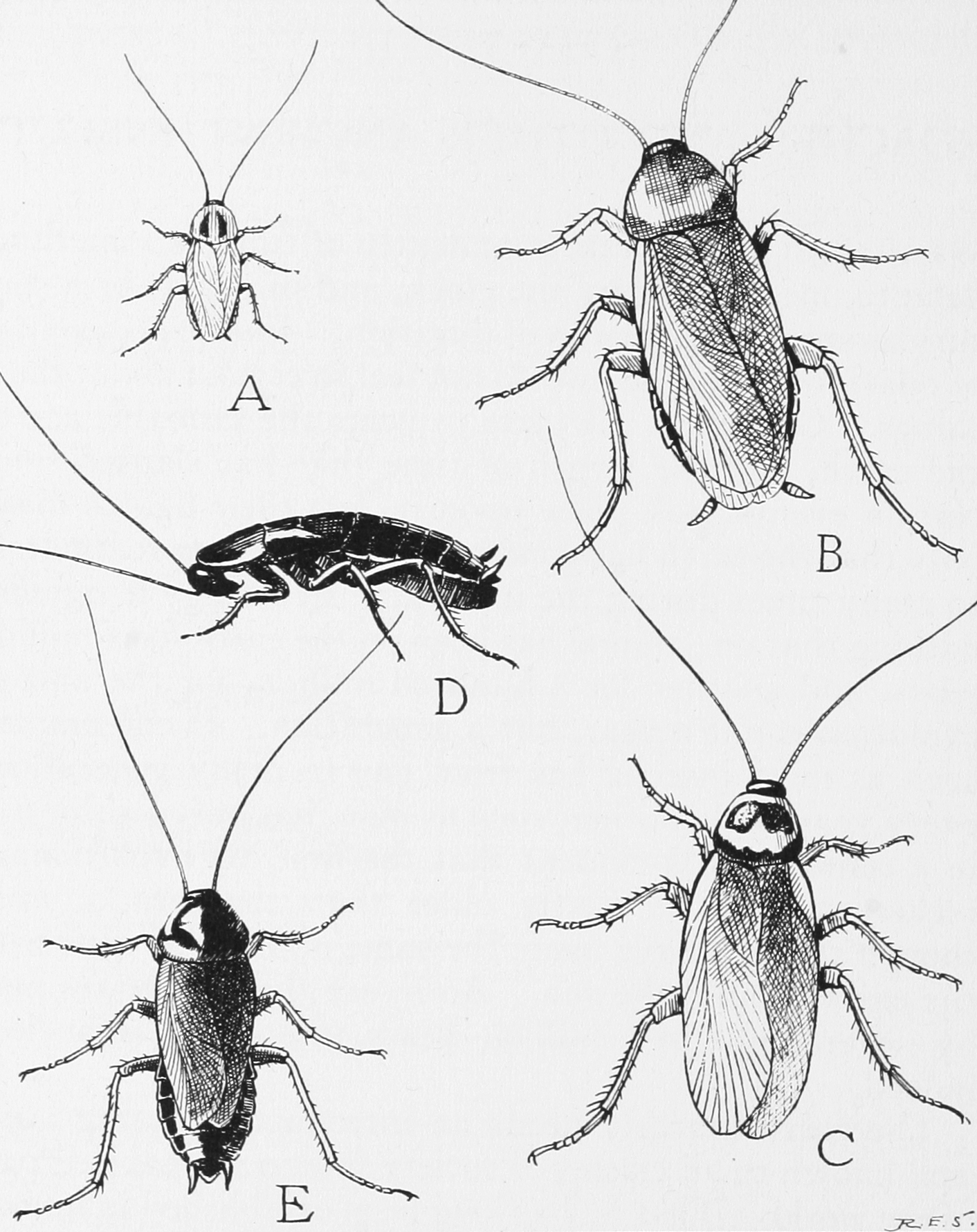

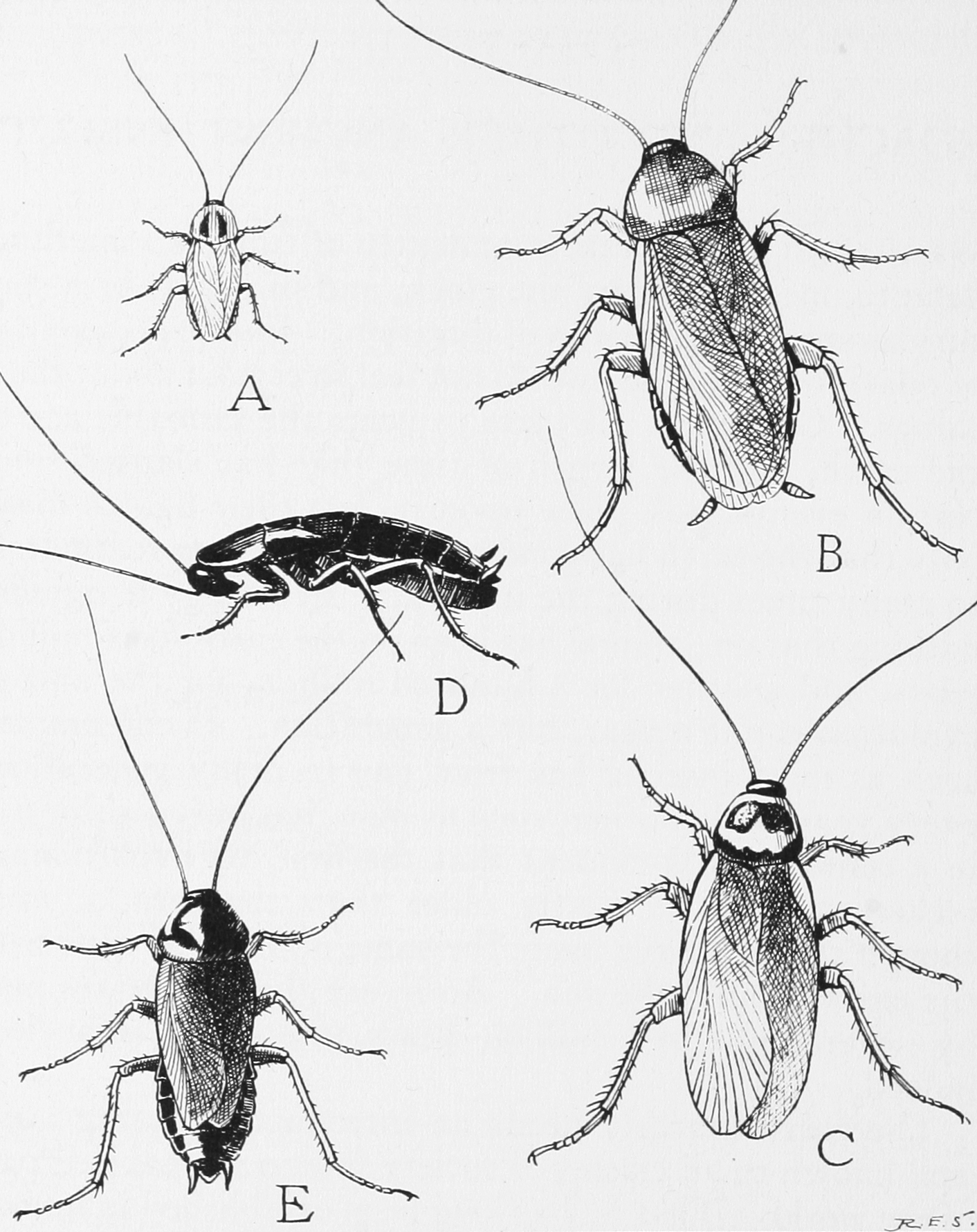

The off-white stuff is actually fat, which encases a cockroach’s organs, circulatory and nervous systems, a thick layer of goo between the tough cuticle of its shell and its delicate insides. This fat body, as it is called, is where much of the insect’s metabolism goes on, and where it stores precious nitrogens and other nutrients to have on hand in case food gets scarce. In fact, if they have access to water, German cockroaches, Blattella germanica, the most common domestic roach in the United States and the species we usually see in our kitchens, have been observed to live forty-five days without food, and with neither food nor water they can still survive more than two weeks. Other species, most notably the Periplaneta americana, the second most common domestic roach in the U.S., can live much longer. With water, Periplaneta has been observed to make it as long as ninety days without food, and has gone some forty days in the laboratory with neither food nor water. In all species, the females are able to do without for longer than the males.

The cockroach, regardless of species, is built for survival. This is the case for many insects, but cockroaches, as far as we know, are the oldest insect still abroad on the planet, a tremendously successful design in evolutionary terms. Like all insects, they have six legs and a shell made of a hard substance called chitin. Their heads are permanently bent down beneath their carapaces, or shells, with a pair of antennae sticking out in front. Seen in profile, a cockroach’s head is always bowed. Its waxy exoskeleton and its shape allow it to squeeze into extremely small spaces, and it can utilize a tremendous range of substances for nourishment.

Reprinted with permission from The Cockroach Papers: A Compendium of History and Lore, by Richard Schweid, published by the University of Chicago Press. © 1999 by Richard Schweid. All rights reserved.

This story is made available by Nexus Media, a syndicated newswire covering climate, energy, politics, art and culture.