The dusty hills around Lima sprout concrete at all angles. There are many words here for the gray delineation of poverty-struck areas: áreas tugurizadas (slum zones), the less formal tugurios (projects), solares (tenements), barriadas asistidas (assisted shanty towns).

The average shanty-town income is less than $150 a month, which makes it a difficult place to conduct public health campaigns. In the 1990s, Dr. Jim Yong Kim, now the president of the World Bank, worked with the non-profit Partners in Health (PIH) to identify and then control an epidemic of multiple-drug-resistant tuberculosis in Lima. Kim called it “Ebola with wings.”

Paul Farmer is a physician known for revolutionizing medical care in the developing world, and a co-founder of PIH. He wrote recently, “We learned then that community-based care”—shorthand for a technique Farmer has developed that provides for patients’ basic needs, in addition to strictly medical treatment—”delivered in large part by community health workers, was not only safer than facility-based care, it was also more effective.” Now, after traveling to Liberia, Farmer says that West Africa needs similar support to cope with its recent Ebola epidemic.

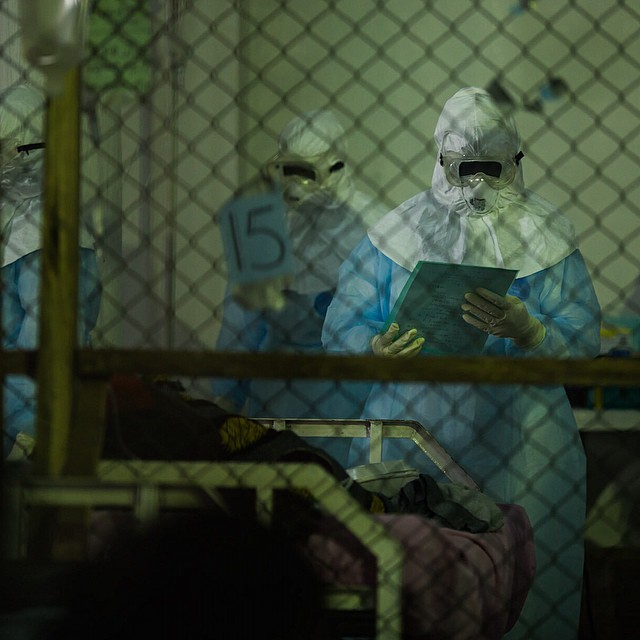

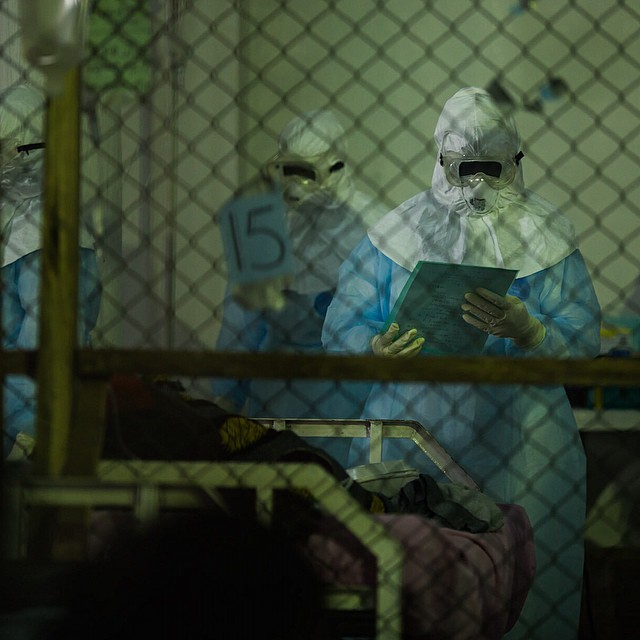

Only 18 percent of Ebola patients in Liberia are currently being cared for in specialized treatment units. The rest are at home or in hiding, afraid of being dragged to overcrowded, understaffed hospitals. This greatly increases the risk of contagion, because patients can be highly infectious, and the people caring for them are usually not using proper protective equipment. According to the CDC, the number of patients reaching specialized treatment centers needs to increase to 70 percent for the outbreak to be controlled—a difficult task in countries struggling with social unrest, lack of education about the disease, poverty, and fear.

In the absence of hospital-based treatment, it’s the people tending the sick, predominantly women, who are at the greatest risk. Farmer writes, “It’s no accident that up to 75 percent of those afflicted with Ebola are women.” If mothers and daughters are becoming default nurses, it’s imperative that they be equipped for the job.

“The idea that some lives matter less is the root of all that is wrong with the world.”

Farmer’s lifelong quest to provide “preferential care to the poor” has landed him on the unusual side of many arguments. He writes that what’s important in curing disease is “staff, stuff, space, and systems required to prevent, diagnose, and treat.” He’s now advocating a realistic approach that distributes protective equipment to the people who are exposed, whether or not they are affiliated with hospitals. “The countries fighting Ebola need to have the tools to treat patients closer to their homes and communities,” he says. Right now, patients who don’t want to go to hospitals or have difficulty reaching them can’t be cared for without putting others at risk.

Farmer’s focus is on accomplishing medical objectives, even if the means to those objectives include distinctly non-medical care. If the patient needs money and food to get to the clinic, Farmer’s opinion is that those stages should be considered part of treatment too. “Community-based care does not mean ‘community-based no-care,’” Farmer told a panel at the Clinton Global Initiative meeting in New York this week.

In Lima, that meant a model where money went not only to providing first-class drugs, but also food, transportation, and even mental counseling. As Farmer said at a commencement speech at the Harvard Kennedy School of Government, “accompaniment” became the central emphasis of his comprehensive health care approach. “To accompany someone is to go somewhere with him or her, to break bread together,” he said. “I believe we introduced the term “donkey rental fee” to the health policy literature.” But the results of his holistic approach were persuasive. In less than three years of work implementing simple programs like using community-based workers to ensure patients stayed on their treatment schedules, cure rates for multi-drug-resistant tuberculosis in Lima reached 83 percent.

West Africa needs more, better-equipped Ebola treatment units, as well as long-term commitments to improve public health infrastructure in order to control epidemics like this, but right now it also needs tools to help protect health workers—whether or not they are trained professionals—who are fighting the virus in villages and neighborhoods. “The idea that some lives matter less is the root of all that is wrong with the world,” Farmer told writer Tracy Kidder. As the international health community steps up efforts to control the spread of Ebola, it’s worth remembering.