Given a choice between eating chocolate alone and rescuing their pals, rats will apparently save their pals and then share the chocolate with them. Trapping a rat in a cage sparks its cagemate into action, as it figures out how to open the cage and liberate its jailed friend. This is an unusual example of rats expressing empathy, a trait thought to be reserved to us higher mammals, the primates.

It’s interesting from an evolutionary perspective, because it suggests that pro-social behaviors originated earlier than previously thought. And it’s interesting from a neuroscience perspective, because it suggests rats are wired for pro-social behaviors, which means they can be used as a model for human behaviors.

“There are a lot of ideas in the literature showing that empathy is not unique to humans, and it has been well demonstrated in apes, but in rodents it was not very clear,” said study co-author Jean Decety, a psychiatry and psychology professor at the University of Chicago. “We put together in one series of experiments evidence of helping behavior based on empathy in rodents, and that’s really the first time it’s been seen.”

The simple experiment used no fancy technology and no bizarre new methods — it just separated two rat friends that normally shared a cage and watched what happened.

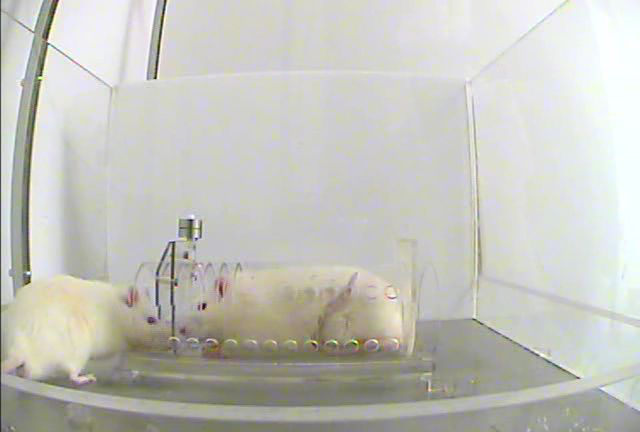

The rats started out sharing a cage for two weeks, enough time to get acquainted. Then the animals were placed in a special chamber, where one rat was inserted into a cramped restraining device that could be nudged open from the outside. The other rat was free to roam around and observe the plight of its jailed pal, both squeaking ultrasonic alarm calls all the while.

The free rat was agitated when its cagemate was trapped, which the researchers say is evidence of “emotional contagion,” a lower form of empathy in which animals share in the fear or distress of another animal. But what happened next was much more like true empathy. Although the rats were agitated, they didn’t freak out, freeze or become overwhelmed with fear, which is one possible reaction to emotional contagion. Instead, they coolly circled the container, bit it, clawed at it and generally spent time near it, even reaching through holes to touch (and comfort?) the trapped rat.

The researchers tried several different controls to figure out what was motivating the rats. They experimented with empty cages, to ensure the rats weren’t just curious about the box-thing, and they found the rats ignored the empty ones. They tried keeping the rats separate even after liberation — socialization would be a reward for freeing the trapped rat — yet the rat still freed its friend.

They even tried a “cagemate versus chocolate paradigm,” the authors explain. A free rat was placed in an area with two containers, one containing its cagemate and one containing pieces of chocolate. It would open the chocolate cage about as often as the rat cage, suggesting “the value of freeing a trapped cagemate is on par with that of accessing chocolate chips.” But more than half the time, the free rats did not hog all the chocolate chips. They saved them and let their liberated cagemates have half of them.

The rats figured out several different ways to open the door, and the researchers say they clearly learned what would happen. “Whereas rats initially froze after the door fell over, later on they did not freeze, demonstrating that door-opening was the expected outcome of a deliberate, goal-directed action,” they write.

Female rats were also more likely to become door-openers, “which is consistent with suggestions that females are more empathic than males,” the authors added.

?Inbal Ben-Ami Bartal, the paper’s first author, said in a statement that the rats were not trained at all, but figured out how to complete a difficult task to help their cagemates.

“These rats are learning because they are motivated by something internal,” Bartal said. “They keep trying and trying, and it eventually works.”

The study is published in this week’s issue of Science.