In photos: updating New York’s vast and fragile telecom backbone

The cables that keep information flowing through the Big Apple are undergoing a transformation, from aging copper to strong and fast fiber.

The cables that keep information flowing through the Big Apple are undergoing a transformation, from aging copper to strong and fast fiber. In telecom buildings around the city, lines that once snaked across huge frames now feed into compact fiber-optic hubs.

In the topmost of five subbasements at 140 West Street in Lower Manhattan, Verizon phone and data lines wind in from the surrounding neighborhood to connect customers with switches and network hubs upstairs. The thick, black sheaths house copper cabling, which the telco giant is working to phase out. The yellow tubes tucked up close to the ceiling hold the new fiber-optic lines. These conduits manage the same data haul as copper, but in far less space.

Telecom workers pop open manholes throughout the city to extend the five-times-faster fiber network into more buildings and neighborhoods. The existing lines snake through orange and gray tubes below the street, so workers must pull them above ground to connect new stretches of the glass-based cable. The fragile copper it’s replacing (seen encased in black) corrodes when wet and, if broken, requires laborious manual mending.

In a clean truck above the open manhole, workers fuse the surfaced fiber to fresh cable (seen wrapped around a frame on the right of the workbench) in a process called splicing. A purpose-built machine (at left) hits 3,632 degrees to melt and join the lines. The screen shows the fiber’s internal glass strands (there can be 24 per cord) and indicates when each new link is working. The process takes seconds, but the two-man teams need anywhere from 30 minutes to a few hours to repeat it for each cable of fiber at a given job site.

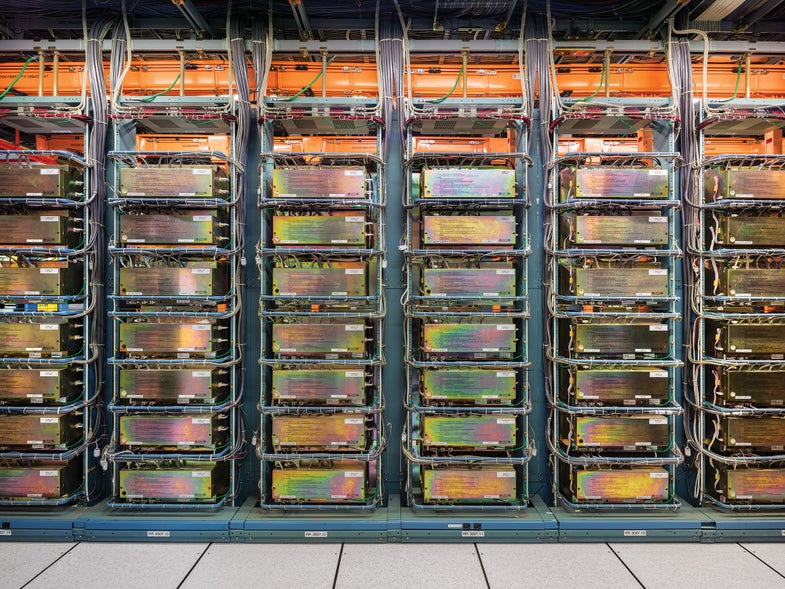

Back at 140 West Street, networking equipment shuffles the fiber-optic demands of customers: packets of Netflix streams, Facebook updates, or business dealings from One World Trade Center across the street. These light-based signals can travel farther and faster than the electrical pulses in copper-based DSL lines, and use only a fraction of the energy.

This article was originally published in the January/February 2018 Power issue of Popular Science.