We’ve known for a number of years that adults 65 and older are more likely to share fake news on the internet than 18 – 29 year olds. It remains a tricky conundrum to deal with as the amount of smartphone, tablet, and social media users over 65 have continued to grow in the past decade, according to a Pew survey this year. And fake news spreads fast.

Many researchers have been testing interventions such as digital literacy programs and online tipsheets to help older adults familiarize themselves with new information in online environments. But are these efforts actually effective? A new study published in Scientific Reports by researchers from Stanford University in April finds that these programs work.

They found that adults who participated in an hour-long course training them to identify and verify the credibility of online information performed better in a fake news assessment test than a control group who did not receive any training.

In the researchers’ testing, 143 adults around 67 years old who took the online course served as the experimental group, and 238 adults around 63 years old who didn’t take the course served as the control group.

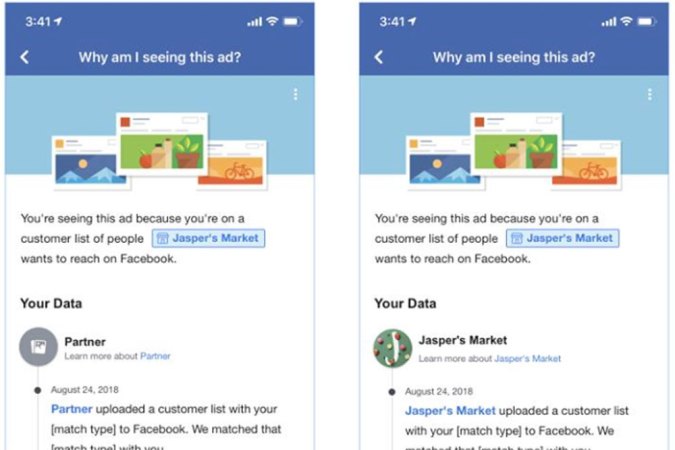

For the online course, a non-profit journalism initiative called MediaWise provided a digital literacy training program during the 2020 presidential election in the United States. This course used text, videos, interactive exercises, and short quizzes to teach participants how to check the accuracy of information they found online. This includes showing them how to do “lateral reading,” or browsing the web to see what other sources are saying about a certain claim, and performing reverse image searches to see if a photo was doctored or taken out of context. The course also focused heavily on Facebook, since it is the most popular platform among older adults.

[Related: Curious about what’s in ‘The Facebook Papers’? Read them for yourself.]

Before taking the course, both the experimental and control groups were asked to complete a survey containing a “deception detection task” that asked participants to judge whether six news headlines were true or false. After the course was finished, both groups were given another similar survey with six different headlines. Each set of headlines included two Democrat-leaning headlines, two Republican-leaning headlines, and two headlines unrelated to politics. In the group that took the online course, their assessment scores increased from an average of 64 percent in the first survey to an average of 85 percent in the second survey. The control group that did not take the course had an average accuracy rate of 55 percent in their first survey and 57 percent in their second.

“Unlike younger individuals, older adults are not “digital natives” and may have less experience using contemporary media technologies and platforms as they were not as large a part of their professional and personal lives,” the researchers wrote in the paper. Therefore, they suggest that additional training programs like MediaWise’s could provide these adults with the basic research skills they need to vet new information they encounter online.

[Related: How to tell science from pseudoscience]

The researchers acknowledged it was possible that people who signed up for the MediaWise course in the first place might have a greater motivation to improve their digital media literacy skills than those in the control group. So, to even out any potential bias, they measured the control group’s motivation to learn online skills through a question in the first survey that asked if they would be willing to participate in the MediaWise program (no one from the control group ended up taking the course). After comparing the control subgroup that answered ‘yes,’ with the experimental group, the results still followed a similar trend. The group that took the course was still able to judge the accuracy of headlines better than the control subgroup that did not take the course.

“The older adults who took the MediaWise for Seniors intervention showed an improved ability to accurately classify true and false news after taking the course, displayed greater comprehension of several skills important for identifying misinformation online, and were more likely to report doing research on news stories before making judgments about their veracity,” the authors wrote in the paper. “None of these changes were observed in a control group of older adults.”