What’s the weirdest thing you learned this week? Well, whatever it is, we promise you’ll have an even weirder answer if you listen to PopSci’s hit podcast. The Weirdest Thing I Learned This Week hits Apple, Anchor, and everywhere else you listen to podcasts every-other Wednesday morning. It’s your new favorite source for the strangest science-adjacent facts, figures, and Wikipedia spirals the editors of Popular Science can muster. If you like the stories in this post, we guarantee you’ll love the show.

FACT: Albert Einstein almost got conned into some serious sexual pseudoscience

By Hannah Seo

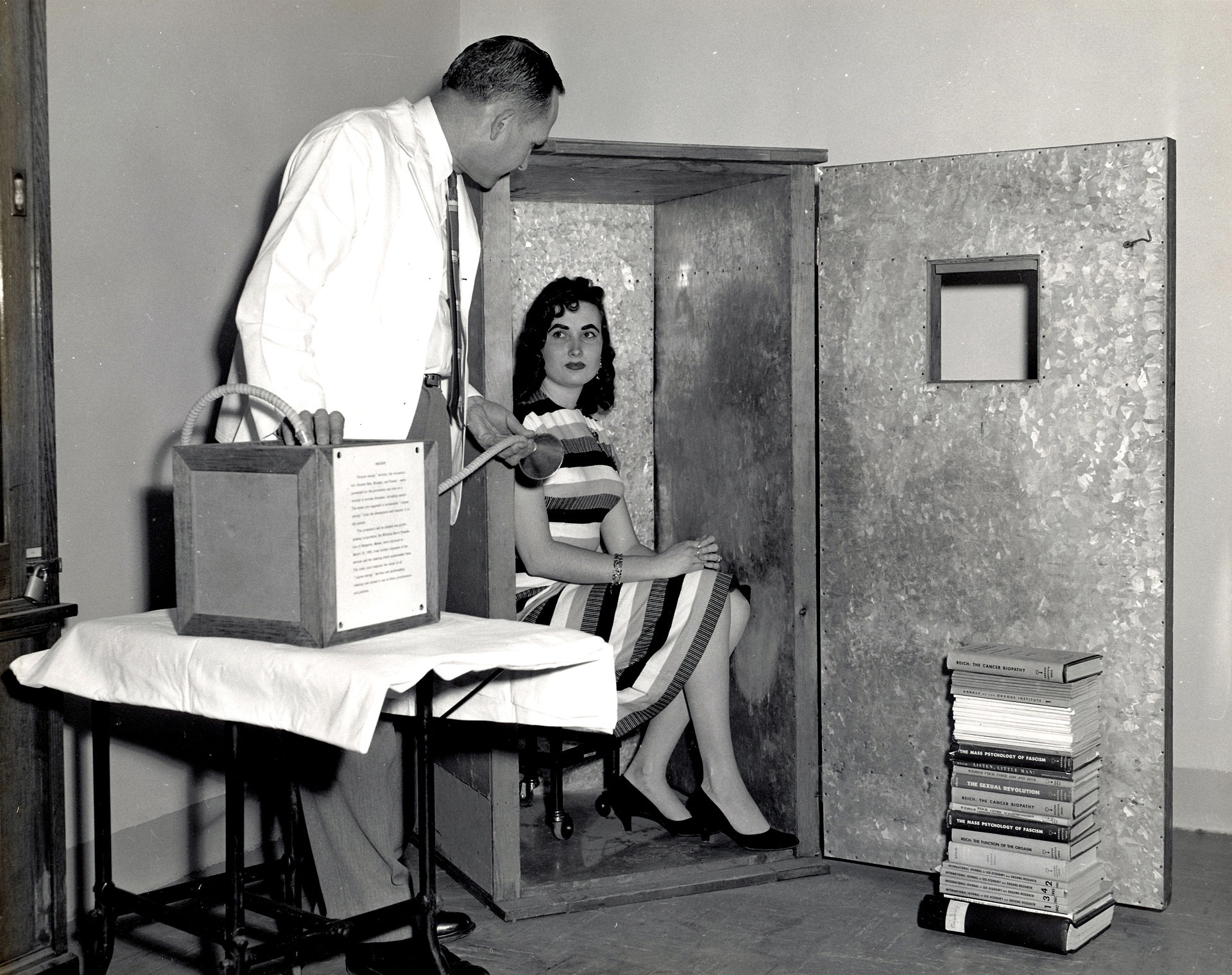

Psychoanalyst Wilhelm Reich thought he had discovered the cosmic source of all sexual energy. This energy, “orgone,” was supposedly a life-force of sorts. What’s more, Reich believed that a looser view of sex would free society from the psychological hang-ups preventing people from reaching their orgastic potential.

He even started building and selling “orgone accumulators,” which he said could concentrate a person’s orgone energy when they sat inside them. Unfortunately for Reich, the psychoanalysis community shunned his outlandish claims, and scientists across Europe and America denounced his so-called science.

While Reich is pretty unknown today, at the time he was a huge figure, and his story intersects with a lot of notable figures: Sigmund Freud, J. Edgar Hoover, and even Albert Einstein. There’s also the Wilhelm Reich Museum, located at “Orgonon” in Rangeley, Maine, which was previously Reich’s estate—where he conducted questionable orgone research in the later years of his career. Listen to this week’s episode to learn more!

FACT: This beetle cheats death by making its enemies poop

Normally, when a predator eats prey, that transaction is complete. But a team of biologists at Kobe University in Japan found that for one species of beetle, that’s just not the case. The scientists initially noticed that this species, called Regimbartia attenuata, had a habit of hanging out rather nonchalantly with frogs on paddy fields in Japan. This seemed strange, because frogs tend to eat beetles.

The team took the frog and beetle duo into a lab setting to observe them more closely. Unsurprisingly, the frogs did try to capture the beetles—and generally succeeded in swallowing them. But then, strangely, as little as six minutes later, the frogs would poop and the beetles would emerge, very much alive.

If you think this is the most—or the only—bizarre thing a beetle has done to evade capture, think again: Other sorts of beetles have been found to force frogs to puke. Then there are the aptly-named bombardier beetles, which can discharge noxious and boiling hot chemicals from their abdomens when under attack.

FACT: You’ll probably never eat more than 84 hotdogs in 10 minutes

We’ve talked about the four minute mile and we’ve talked about the two hour marathon, but this week I’m here to opine on another athletic feat—eating 84 hotdogs in 10 minutes.

In July, a veterinarian and sports scientist named James Smoliga decided to analyze competitive eating the same way he and other researchers have previously analyzed other competitive sports—by plotting out how performance has improved over time, and trying to use that data to determine where human abilities will peak.

As it turns out, competitive eating—specifically Nathan’s famous hot dog eating contest in Coney Island—has followed the same basic performance curve as most sports. First, things are amateurish across the board: Everyone is learning to play the sport at the same time, because it’s new, so no one is particularly good at it. Natural talent or physiological advantages might give you a slight edge, but even a prodigy isn’t going to master all aspects of a game they’ve never played before instantly.

From here, performance rises slowly and steadily. People learn to play, the game attracts new talent, and people start developing strategies. Then, suddenly, a boom: The sport has developed enough of a fan base to incentivize people to get good at it. Now people are training diligently, tuning their bodies to suit the needs of the sport, and otherwise dedicating their lives—and tons of resources—to being the best.

But that can’t continue forever, because human bodies have inherent physical limits. On this week’s episode of Weirdest Thing, I explain why competitive eating has reached a performance plateau—and what it would take for a professional eater to reach the literal limits of human swallowing speed. And just in case you’re wondering: Yes, competitive eating is incredibly dangerous. But that’s not because your stomach is liable to explode.

If you like The Weirdest Thing I Learned This Week, please subscribe, rate, and review us on Apple Podcasts. You can also join in the weirdness in our Facebook group and bedeck yourself in Weirdo merchandise (including face masks!) from our Threadless shop.

Correction: A pervious version of this post stated that the Reich Museum is located in Orgonon, Maine. In fact, the Orgonon estate—home of the museum—is located in a town called Rangeley. We regret the error.