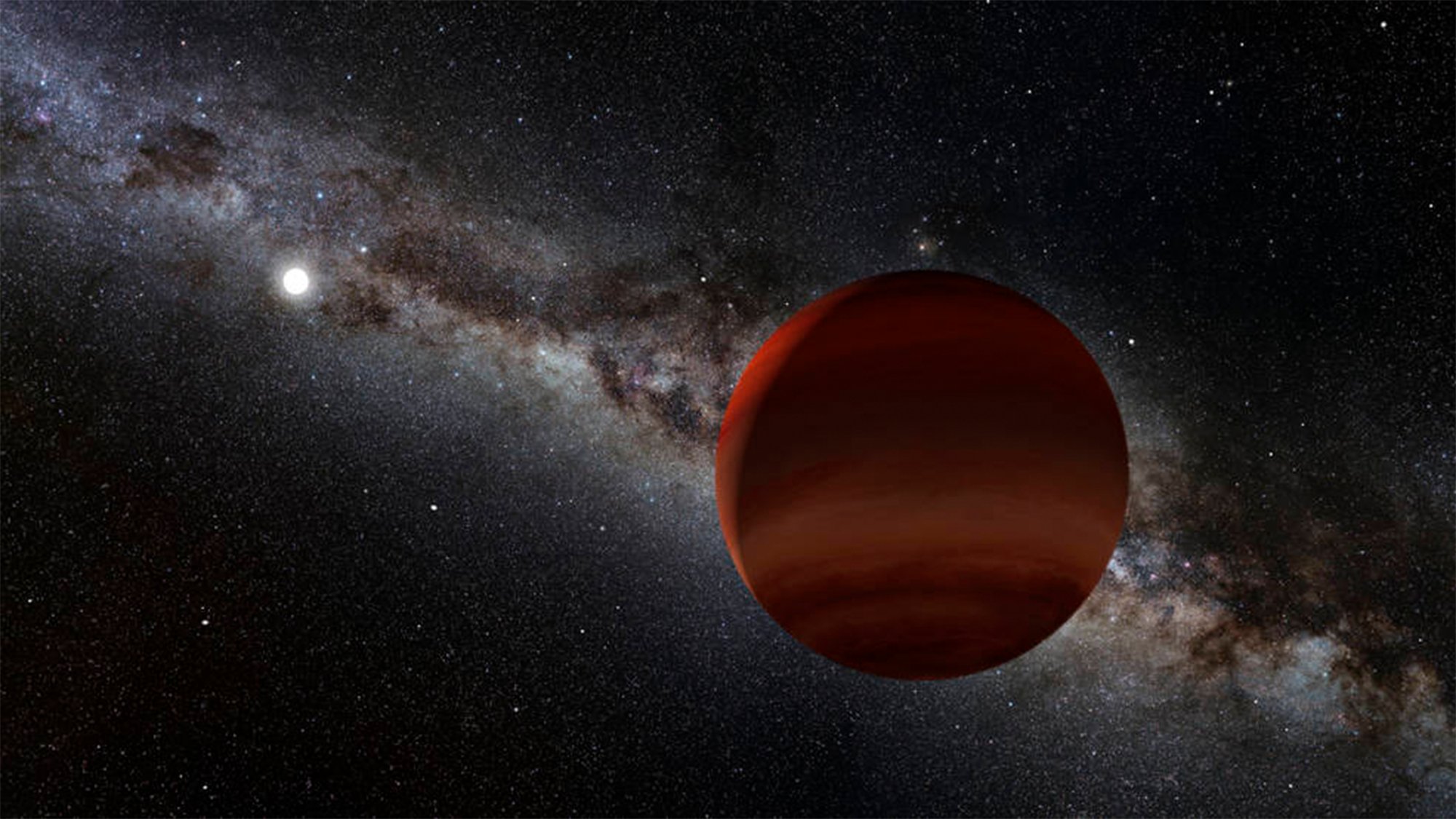

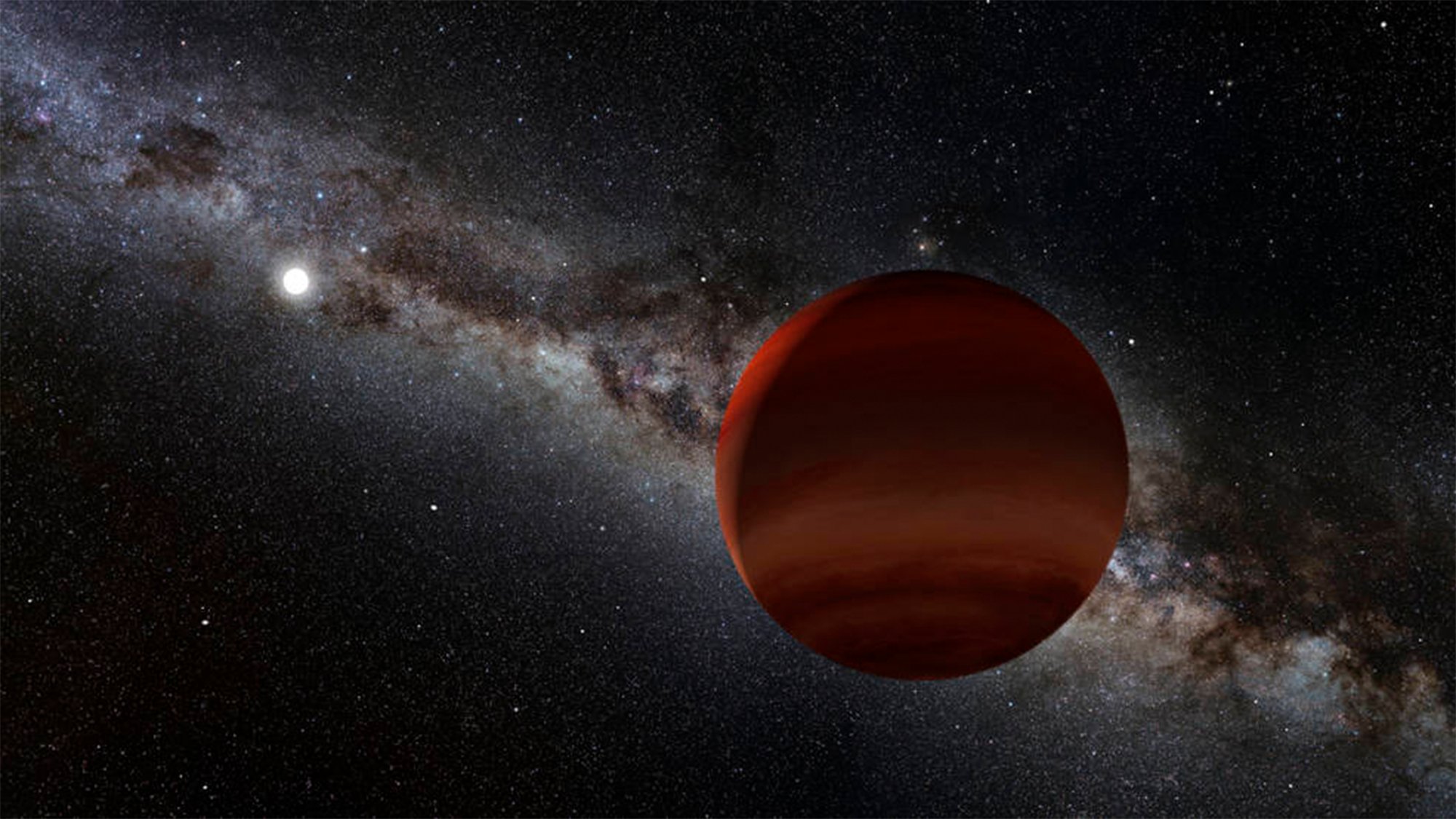

A group of astronomers found that a small, faint “brown dwarf” star is the coldest star yet recorded that still produces emission at radio wavelength. The findings were published last week in The Astrophysical Journal Letters and describe a star that is only 797 degrees Fahrenheit, compared to campfires on Earth which can hit 1500 to 1650 degrees.

[Related: Your guide to the types of stars, from their dusty births to violent deaths.]

The “ultracool brown dwarf” named T8 Dwarf WISE J062309.94−045624.6 is not the coldest star ever found, but it is the coolest to be analyzed using radio astronomy, according to the team on this study.

“It’s very rare to find ultracool brown dwarf stars like this producing radio emission. That’s because their dynamics do not usually produce the magnetic fields that generate radio emissions detectable from Earth,” co-author and University of Sydney PhD student Kovi Rose said in a statement. “Finding this brown dwarf producing radio waves at such a low temperature is a neat discovery. Deepening our knowledge of ultracool brown dwarfs like this one will help us understand the evolution of stars, including how they generate magnetic fields.”

Astronomers are still questioning the internal dynamics of brown dwarf stars that produce radio waves. They do have a good idea of how larger stars like the sun generate radio emissions, but it is not fully known why less than 10 percent of brown dwarf stars produce these emissions.

It’s possible that the rapid rotation of ultracool dwarfs may play a part in generating their strong magnetic fields. Electrical current flows may be created when the magnetic field rotates at a different speed than the star’s ionized atmosphere. For this star, the team believes that radio waves could be being produced by the inflow of electrons to the star’s magnetic polar region, which when added together with the star’s rotation, is producing regularly repeating radio bursts.

This star is considered a brown dwarf because it does not give off a ton of light or energy, and is not big enough to ignite nuclear fusion the way our sun and other stars do.

“These stars are a kind of missing link between the smallest stars that burn hydrogen in nuclear reactions and the largest gas giant planets, like Jupiter,” said Rose.

[Related: These 5 mysterious space objects straddle the line between planets and stars.]

T8 Dwarf WISE J062309.94−045624.6 was first discovered in 2011 and is about 37 light years from Earth. Brown dwarfs are considered “failed stars” because despite typically being larger than gas giants, they are still smaller than other stars. This particular star’s width is believed to be between 65 percent and 95 percent of the size of our solar system’s largest planet, Jupiter. However, this brown dwarf is somewhere between four and 44 times more dense than Jupiter.

New data from the CSIRO ASKAP telescope in Western Australia followed up with observations from the Australia Telescope Compact Array near Narrabri in New South Wales. The MeerKAT telescope in South Africa also helped make this discovery possible.

“We’ve just started full operations with ASKAP and we’re already finding a lot of interesting and unusual astronomical objects, like this,” co-author and University of Sydney astrophysicist Tara Murphy said in a statement. “As we open this window on the radio sky, we will improve our understanding of the stars around us, and the potential habitability of exoplanet systems they host.”