When tornadoes touched down in Kentucky, Illinois, Arkansas, Missouri, Mississippi, and Tennessee over the weekend, residents and workers had only 20 minutes of warning. More than 70 people are known to have died, but the death toll is expected to climb as first responders search the 200-mile long path of the outbreak.

But that’s about the typical amount of warning for a major tornado, which is forecasted 18 minutes before touching down.

Tornadoes form alongside thunderstorms. But a thunderstorm only spins off a tornado under very specific conditions. Wind at the ground and further above have to be moving in opposite directions. This causes the air between to spin in a horizontal tube. Then, the air on the ground must be warm enough to tip that spinning tube off the ground. And the storm above needs to tug on the top of the now-vertical column, which allows it to grow.

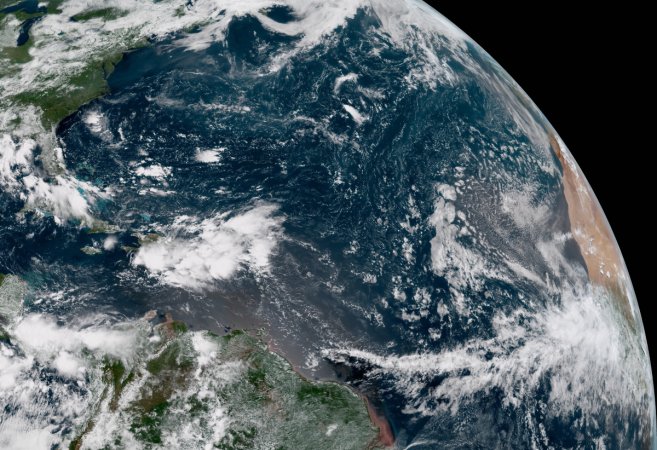

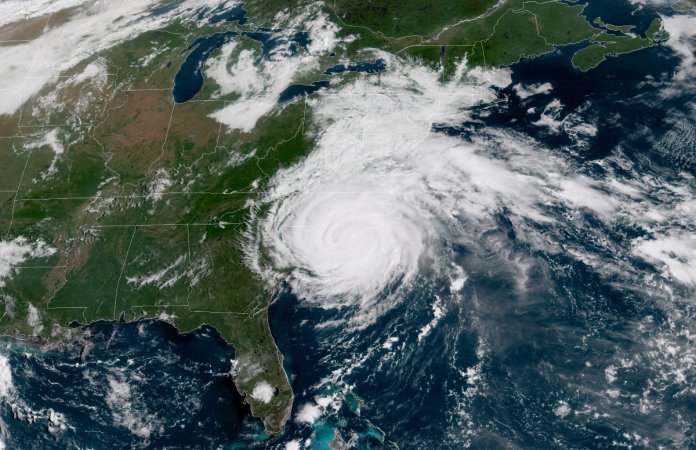

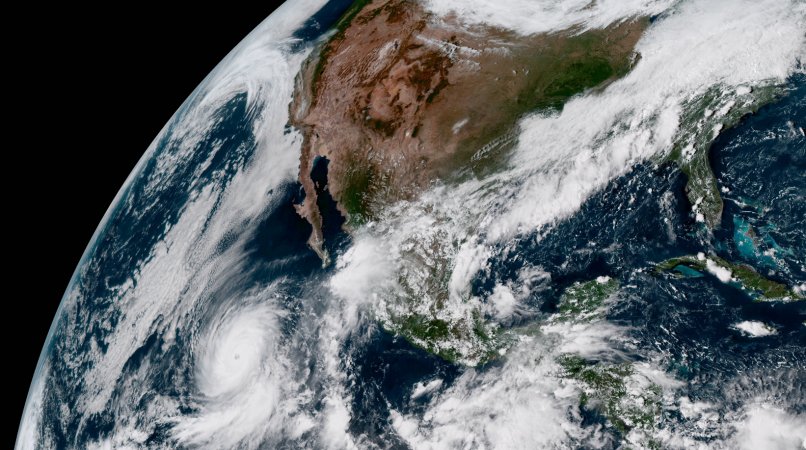

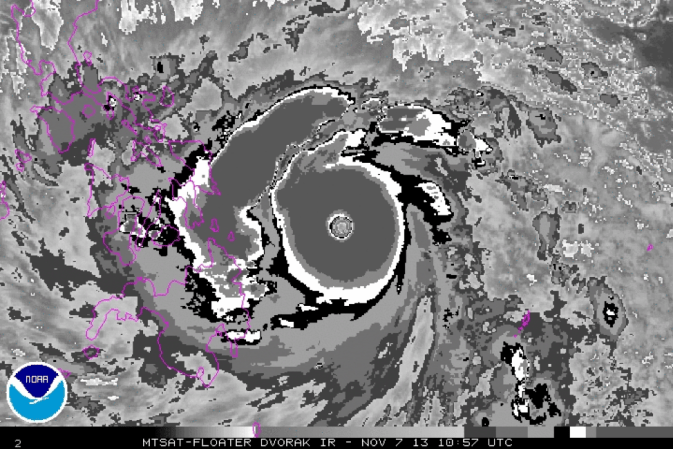

The central challenge with predicting a tornado’s path is that the weather events are extremely local phenomena. Although Friday’s tornadoes moved more than 200 miles, they were less than a mile wide. The average width of a tornado, according to the Federal Emergency Management Agency, is only around 400 yards, which is less than a quarter of a mile or about four football fields. (That might sound big, but hurricanes, which are more easily predicted, are usually around 300 miles wide.) Weather forecasting models often look at phenomena over square miles, and Wired reported in 2019 that advanced tornado modeling only went down to about 2 mile increments.

[Related: Here’s what a terrifying tornado outbreak looks like.]

That means that forecasters can predict the conditions where tornadoes are able to form—specific storms, like supercells and hurricanes, are most likely to spin them off—but are much less good at knowing where they will touch down.

Knowing where they will move is another gap. The speed of the storm, as well as the lack of data on upper atmospheric conditions that affect the path of the tornado, make it hard to guess what will happen once it has formed.

So forecasters need to weigh false positives against false negatives. In about 70 percent of tornado warnings between 2016 and 2020, no tornado appeared, according to data reported by Weather.com. (Watches are issued when the conditions look right for a vortex while warnings are issued when forecasters believe one is imminent.) And because it’s so hard to know exactly where a tornado will move after it touches down, few people in a warning zone will actually be near its eventual path.

Still, forecasters are fairly successful at predicting the worst events. A 2019 study found that 87 percent of deadly tornadoes were forecast in advance, and 95 percent of deaths took place in areas with active tornado warnings.

Predicting how powerful a tornado will become is hard, too. Tornado watches simply say that something is coming, but don’t distinguish between a brief tornado with 100mph winds, and a monster that can obliterate buildings.

“With hurricanes, communities will take different actions depending on whether a Category 1 versus a Category 5 storm is in the forecast,” atmospheric scientist Joshua Wurman wrote in a CNN essay on Sunday. “But with tornadoes, no such detail exists—and people may become complacent to warnings, having experienced false alarms.”

In the case of this past weekend’s storm, the death toll seems to be highest where employers didn’t act on the information they were given. And notably, NBC reported this afternoon that employees in a candle factory in Mayfield, Kentucky, were told that they would be fired if they left early to take shelter. (Company spokespeople dispute the account.) At least eight people died when the factory was destroyed. Insider reported a similar story at an Amazon warehouse in Edwardsville, Illinois. Six people died there on Friday night.

So while there are plenty of false negatives, predictions are good enough to let people know that they’re in danger. Decision makers need to be willing to act on that information.