Hurricane Florence is long gone, but certainly not forgotten in the atmosphere. The storm’s remnant energy and moisture are partially responsible for two tropical systems in the Atlantic Ocean right now. They don’t pose any threat to land at the moment, but the mere presence of a storm anywhere in the ocean is disconcerting for residents still dealing with fallout from Florence’s landfall and historic flooding.

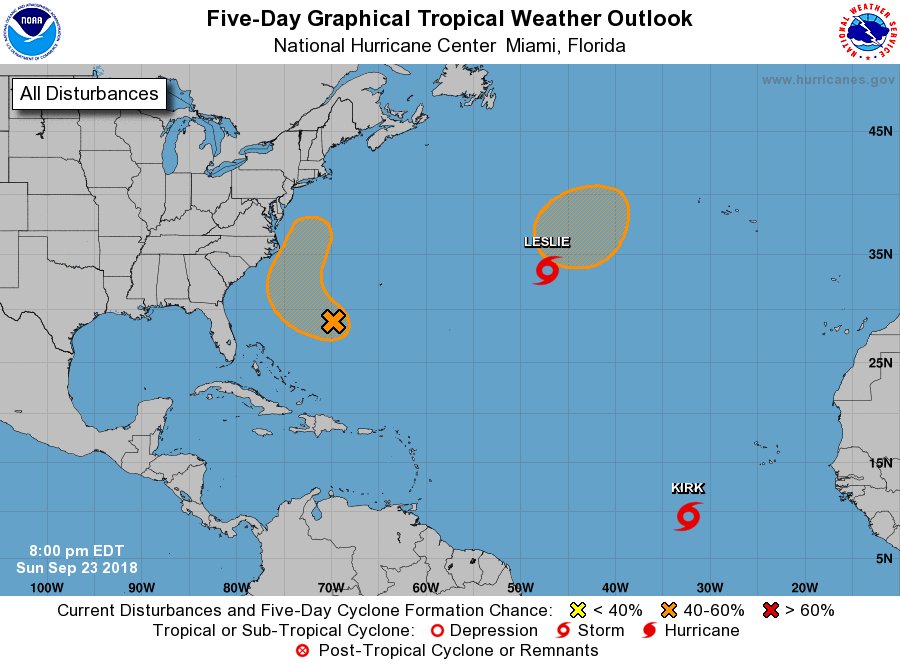

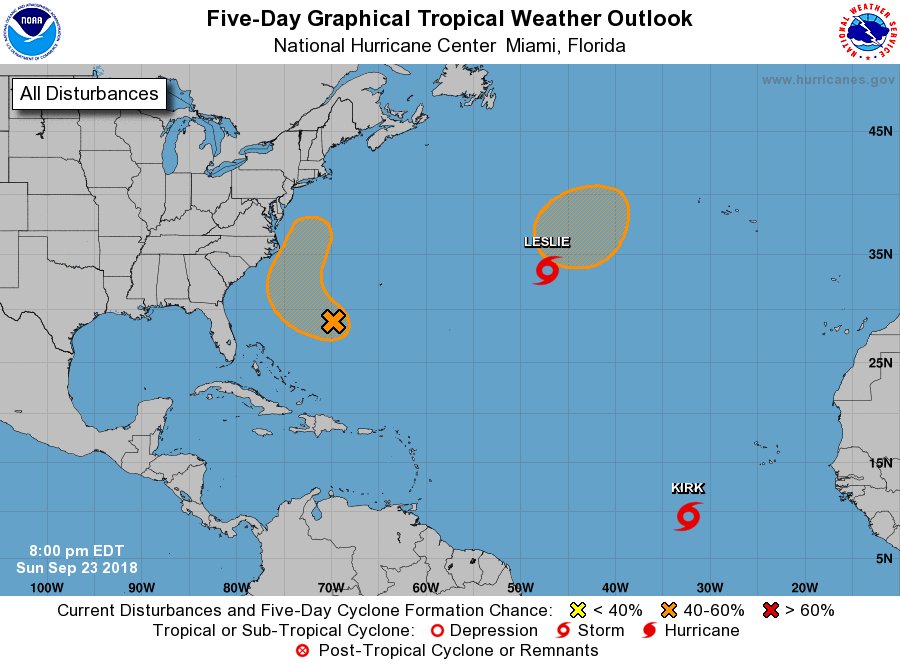

The National Hurricane Center is monitoring the two tropical systems distantly related to Florence. Subtropical Storm Leslie formed in the north-central Atlantic Ocean on Sunday morning. A subtropical storm is a storm that’s partially tropical—the system doesn’t have all-tropical characteristics, but its structure is close enough for the NHC to name it and issue forecasts as if it were tropical through and through. Leslie is expected to be short-lived and shouldn’t affect anyone but ships and planes traversing the ocean.

The second system, located near Bermuda, may become a tropical depression or storm this week as it slowly recurves out to sea. Its proximity to the United States—and North Carolina in particular—is unsettling, but while there’s a chance it may bring some rain to the already-inundated coastal Carolinas, the system shouldn’t be too big of a deal otherwise.

Both of these systems are in small part related to Hurricane Florence. The former storm, which stalled after making landfall near Wilmington, North Carolina, on September 14, 2018, crawled along at an average speed of about 5 MPH for several days after its eye came ashore. Florence’s slow forward speed allowed thunderstorms to drench the same parts of North Carolina for days on end, leading to the historic flooding that killed dozens of people and left a large swath of the affected region without power and largely unreachable by car.

An upper-level trough grabbed what was left of Florence and finally dragged it out of the Carolinas earlier last week. The remnants of the storm darted over New England before spreading out over the northern Atlantic Ocean. The leftover energy and moisture from Florence, now greatly dispersed in the atmosphere, contributed to the formation of both Subtropical Storm Leslie and the disturbance near Bermuda.

It’s not unusual for tropical cyclones to regenerate after they’ve dissipated. Some storms even get their names back when they find new life.

Hurricane Ivan is the most notorious example of a storm regenerating long after landfall. The storm hit Alabama with 120 MPH winds on September 16, 2004. It raced inland after devastating coastal areas, producing a historic tornado outbreak across the Mid-Atlantic before moving over the western Atlantic. The remnants of the storm moved south along the coast, crossed Florida, and redeveloped as a tropical storm in the Gulf of Mexico a week later on September 22. The NHC renamed the system Ivan “after considerable and sometimes animated in-house discussion” among the agency’s hurricane experts. The second birth of Ivan made landfall in western Louisiana on September 23.

However, a system has to keep its core identity after losing tropical characteristics in order to earn back its name, and that’s certainly not the case this week. Neither the subtropical storm nor the disturbance being monitored are direct descendants of the late Florence—they’re just influenced by it. The closest analogy would be to call the current systems distant kin. But while Florence may not be returning from the grave, there is something admittedly spooky about such a devastating storm continuing to influence our weather.