Just last year, three startups threw down the gauntlet in the race to dethrone Google Earth as the king of satellite imaging. In recent weeks, another startup entered the fray, offering more satellites in its toolbox than any competitor which preceded it.

BlackSky Global, a “satellite-imaging-as-a-service” startup based in Seattle, announced it plans to launch 60 satellites into space by 2019 to image the planet in near real-time. The 60 satellites plan more than doubles the number of satellites presented by its competitor Planet Labs, which deployed 28 to space in January 2014, or Skybox, a Google-owned startup which plans to deploy 24 by 2018 (Google itself currently sources its satellite imagery for Google Earth from a variety of small commercial satellite companies, according to the BBC.)

BlackSky Global hopes that once its regiment of satellites is in full swing, it can provide high-resolution images of any place on Earth in a couple of hours upon request for under $100 per photo.

That type of quick turnaround and clear resolution is rare for the industry. And BlackSky Global believes it will be useful for agriculture, forestry, and engineering, among many other industries. In cases of disaster, like a large-scale earthquake or a plane crash, the satellite images can quickly pinpoint the areas that have suffered the most damage, allowing emergency responders the ability to take more drastic action and potentially save more lives.

“By reducing the time it takes to receive a satellite image from days or weeks to just hours or less, BlackSky is able to provide this view much more frequently, enabling responders to make decisions and act more quickly in the most critical scenarios,” said BlackSky CEO Jason Andrews in an email to Popular Science.

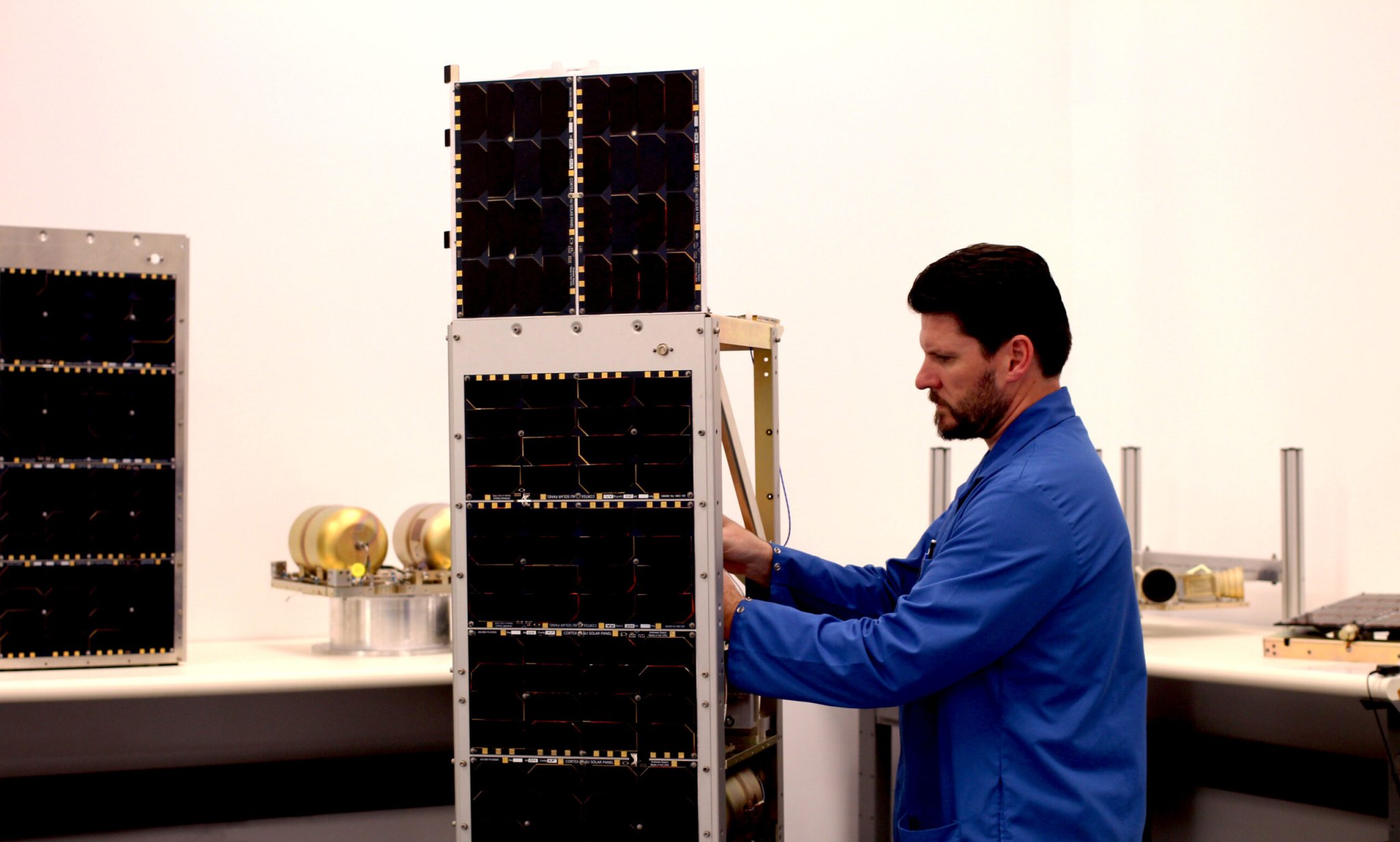

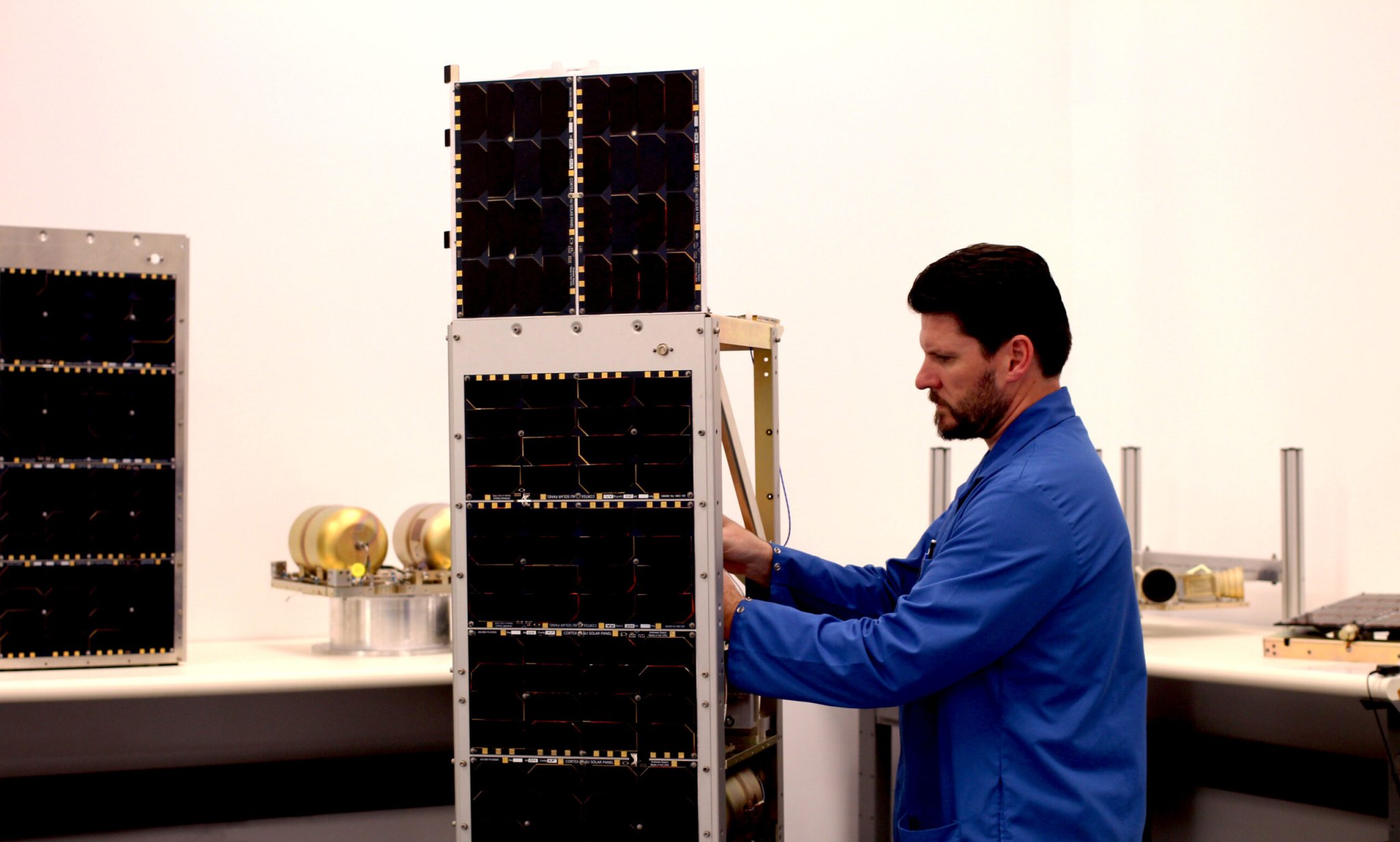

Once prohibitively expensive, satellites in recent decades have become much more affordable and portable. The advent of CubeSat nanosatellites by researchers developed at Stanford and Cal Poly in 1999 has given access anyone from governments to individual hobbyists to build and launch satellites on a mass scale.

The per-satellite construction costs of CubeSat-like craft are much cheaper than their bigger predecessors. Planet Labs’ satellites cost less than $1 million each, while BlackSky Global’s slightly larger satellites cost about $5 million each. Both pale in comparison to the NASA satellite Landsat 8’s $850 million pricetag — considered the “gold standard” for aerial satellite imagery by many.

If BlackSky Global and Planet Labs’ approach is quality through quantity, other competitors have gone a different route where they modify on existing satellites to image the planet. The Vancouver-based startup Urthecast partnered up with the Russian segment of the International Space Station to install two high-definition cameras on that very large satellite earlier this year.

Last week, Urthecast published the first HD videos from the space station: richly detailed, wildly colorful scenes of cities like Boston and London, with ant-sized cars moving in real-time. Earlier this week, the company purchased Deimos Imaging, a Spanish satellite imaging firm, to potentially build its own satellites.

The growing technology in real-time satellite imagery and the democratization of access beyond governments and militaries to private industries have reaped millions of dollars in capital to continue the race.

Planet Labs has raised $160 million since it was founded in 2010. BlackSky Global’s parent company Spaceflight Industries have raised over $28 million, including some from Microsoft co-founder Paul Allen’s venture capital firm, according to The Seattle Times.

With satellites ready for action in space currently or in the near future, the startups are divided in what role they will play once they obtain the images. While some startups can provide analysis and trends gathered from its photos as an added commodity, most like BlackSky Global plans to solely sell the photos.

“BlackSky Global is a wholesale provider of pixels, not an ‘answers company’ that analyzes the data,” Andrews said. “We are just capitalizing the constellation and will lease out to our customers the telescopes on the systems.”

With so much startups vying to have its own constellation of satellites in the air by the end of the decade, the satellite imaging industry is set for a huge liftoff. Stakes may be rising quickly, but Andrews demurred from casting BlackSky Global’s anything but competitors.

“It’s of note that BlackSky’s constellation will complement other existing imagery providers, enabling a new level of global awareness by providing images of the Earth in near real-time,” Andrews said. “We view these other companies as customers — not competitors.”