Some kids may very well have magical superpowers. About one in 10 children infected with HIV have a built-in mechanism in their immune system that protects them from developing AIDS, according to a new study conducted in South Africa.

Despite high levels of the virus in their blood, the children’s immune systems stayed calm and did not let the infection worsen, researchers reported in the journal Science Translational Medicine. “This is quite unusual because in general the progression from HIV infection to serious disease is more rapid in children than in adults. About 60 percent of kids infected die within two and a half years,” said senior study author Philip Goulder, a pediatric infectious disease researcher at the University of Oxford.

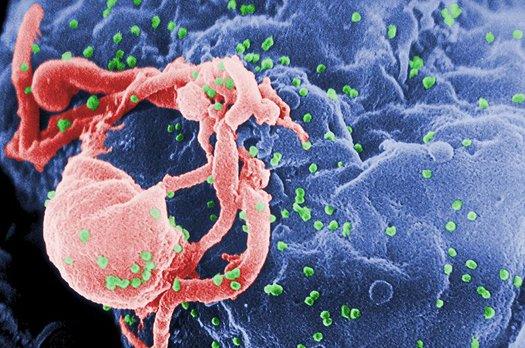

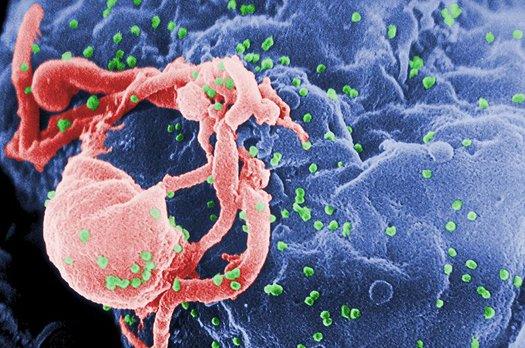

When someone is infected with HIV, the virus usually triggers immune cells into a high alert mode, Goulder explained. It then hijacks some of these cells to replicate itself, killing the immune cells in the process. By wiping out important immune cells, the virus leaves patients vulnerable to other infections–a state called acquired human immunodeficiency syndrome, or AIDS.

In adults, the immune system tends to go all out in a campaign to try and get rid of the virus, but that almost always ends in failure. And the chronic inflammation and immune system overdrive can increase susceptibility to diseases normally associated with aging, such as cardiovascular disease and dementia, even if the virus itself is suppressed by antiretroviral therapy.

For their study, Goulder and his team analyzed blood samples from 170 South African children above the age of five who had never gotten antiretroviral therapy but had somehow evaded AIDS.

The researchers found that the children’s immune systems didn’t get tricked into overdrive by the virus. Instead, their immune cells had conspicuously low levels of a protein receptor called CCR5, which acts like a zipcode telling the immune cells where they need to go to help fight an infection.

In this way, the children’s immune systems resemble those of monkeys that carry a related virus–known as SIV–without getting sick, said Goulder. These monkeys, such as the sooty mangabey and the African green monkey, naturally encounter SIV in the wild but they do not suffer from disease as a result of that virus. Other monkeys native to Asia, such as rhesus macaques, do have CCR5 receptors on their immune cells, and they do develop chronic inflammation and immune deficiency.

“Scientists have known for decades that immune system activation is a crucial step in SIV in monkeys,” said Derya Unutmaz, an immunologist at The Jackson Laboratory for Genomic Medicine, in Farmington, Connecticut “What is exciting about this result is that it recapitulates an important difference seen in African monkeys versus Asian monkeys in how they deal with the virus.”

Although the defense mechanism against AIDS is unique to children, Goulder said it is not clear if they may still need antiretroviral therapy as they grow older. Immune systems usually get more aggressive with age as we get exposed to more viruses and bacteria in the environment, he said. And the virus could be transmitted to others when these kids eventually become sexually active teenagers.

But scientists believe the findings could be used to develop new treatments to help all HIV patients. “This study offers a whole new approach to dealing with HIV,” said William Borkowsky, a pediatric infectious disease specialist at New York University. “Instead of enhancing immune response to the virus with drugs, we may be better off doing the opposite so that adults and children infected with HIV can avoid AIDS successfully.”