Nobel Prize In Chemistry Goes To 3 Scientists Who Uncovered DNA Repair

The discoveries of Tomas Lindahl, Paul Modrich, and Aziz Sancar could help fight cancer

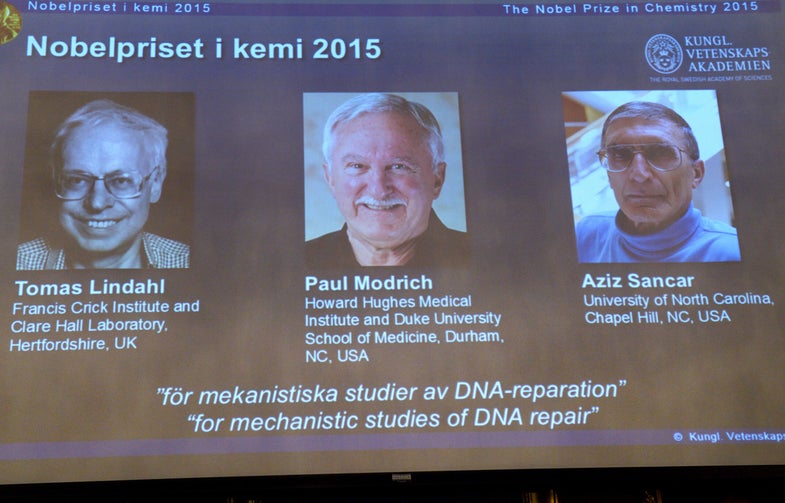

The wait is over for chemistry enthusiasts: today the 2015 Nobel Prize in Chemistry prize was awarded to a trio of researchers, Tomas Lindahl of the Francis Crick Institute, Paul Modrich of Duke University and Aziz Sancar of the University of North Carolina School of Medicine, Chapel Hill, for their mechanistic studies of of DNA repair.

Once thought of as an extremely stable structure, DNA is actually under constant attack. It can undergo literally thousands of spontaneous and causal alterations in the course of a single day — more if you count the defects that can occur during normal cell division.

To repair themselves, cells deploy an army of enzymes that break open DNA and snip out the damaged part. Then they bring in a repair crew consisting of other enzymes.

In addition to occurring in normal cells, that repair process occurs in cancer cells exposed to UV radiation or drugs. Understanding how these repair mechanisms work on a molecular level is vital for the development of more effective cancer drugs, ones that can beat cancerous cells at the repair game.

Sancar is the leader of a research team at UNC that created a repair map of the entire human genome, an achievement that will enable scientists to pinpoint the exact location where repairs have occurred when DNA is damaged by UV radiation or chemotherapy.

He received the news through the time honored tradition of an after-hours phone call. Awoken by his wife, he described the experience to Nobel Media:

“I just got a call half an hour ago, my wife took it and woke me up . I wasn’t expecting it, I was very surprised. I tried my best to be coherent…”

For Nobel watchers who keep score by country, the award to Sancar marks the first time a Turkish-born scientist has won a Nobel prize (novelist Orhan Pamuk received the country’s very first Nobel in 2006, for Literature).

“I am proud for my family, my native country and my adopted country,” said Sancar.

Modrich has been a Howard Hughes Medical Institute (HMMI) investigator at Duke since 1994, with a particular focus on understanding the pathway behind hereditary colon cancer, which is caused by a rare but devastating condition in which the mismatch repair mechanism of DNA is inactive.

In normal DNA replication, the correct pairs of genetic bases, or “letters,” are opposite each other. If one gets misplaced, a mutation could occur. Modrich’s work describes the delicate choreography that occurs when cells are alerted to the discrepancy and take action:

Lindahl is considered a “father figure” in the field of DNA repair for his work dating back to the 1970s, when he first demonstrated that DNA constantly decays and repairs itself, a process called base excision repair.

When he received the news, he was preparing to spend a quiet day in seclusion. “I was going to do some writing at home today but after this message it was decided that a driver will take me to the laboratory,” Lindahl said.

Lindahl feels that the Nobel Prize will help people understand the importance of DNA repair mechanism research. According to Lindahl, by preventing cancer cells from repairing themselves, researchers can develop treatment regimens that enable people to manage their cancer as a chronic condition, similar to the way in which people can live with diabetes.

“It is a very hot topic, not only for cancer but for many diseases, “ he said. “We are getting away from finding a cure, and converting it to something we can live with.”