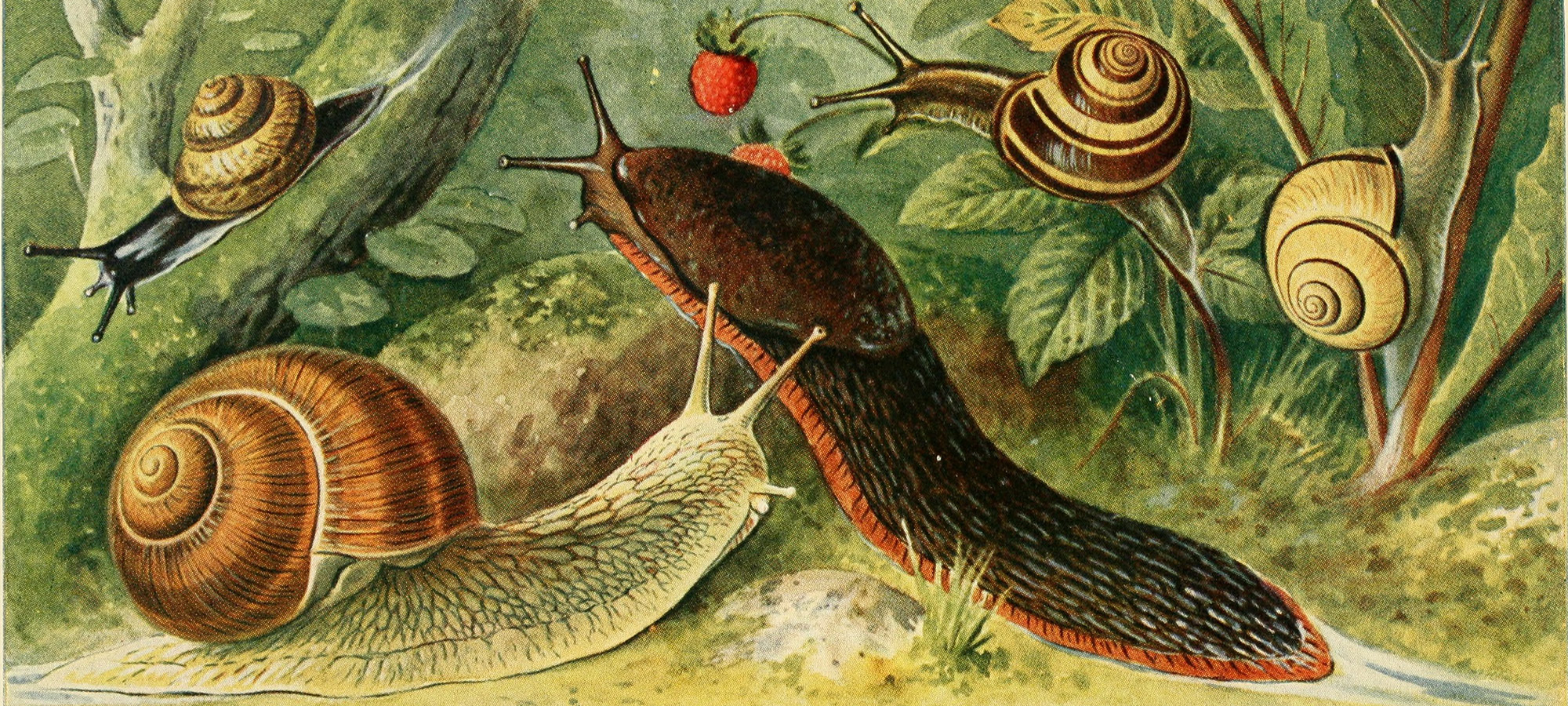

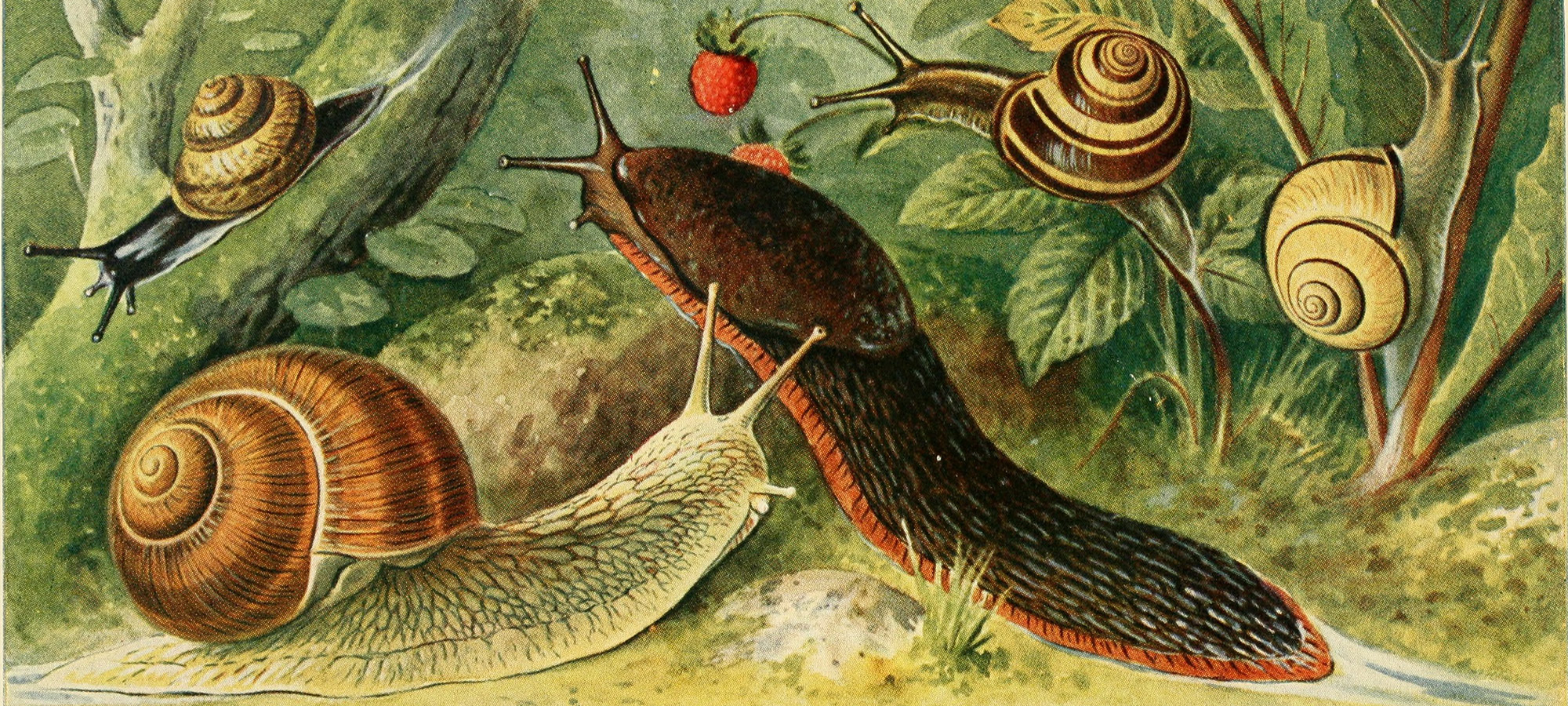

Before he could start farming escargot, Ric Brewer needed to get his hands on some sexually-active snails. Fortunately, in western Washington state, where Brewer now oversees a large and slow-moving herd, that’s as simple as turning over a few leaves. “My mother had all of her church lady friends out in their gardens gathering snails for me,” he says. “They were the founding stock.” Now Little Gray Farms sells about 300 pounds of their offspring each year. Brewer breeds Cornu aspersum, known by its excessively common common name, the “common European garden snail.” The species is often overshadowed by its more soulful or mysterious cousins. The phylum mollusca, to which all snails belong, contains 100,000 creatures: the endless spiral of the nautilus; the brainless but delectable oyster; the seafloor obscenity that is the geoduck. But the snail’s dull shell is hiding a secret all its own. “Even though it’s this homely, kind of bland, not-that-interesting snail,” it’s the main species used in escargot, says Jann Vendetti, a malacologist at the Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County. (The other edible snail is Helix pomatia, also called the Roman or Burgundy snail.) “Petit gris” may be the pride of Paris, but, Vendetti says, it’s “the wet sidewalk snail, just fancied up.”

Humans have indulged in this meaty treat since the Stone Age. Archaeologists unearthed evidence of 30,000-year-old snail shells emptied, cooked, and discarded in Spain. Similarly insightful garbage has been unearthed across the Balearic Sea in Algeria, and along the African coast into Tanzania: snails all the way down.

The preparation may have changed—ancient humans charbroiled their catch, while contemporary Europeans typically sauté snails in garlic sauce—but the fundamental appetite persists. Each year, the French consume some 66 million pounds of escargot. That’s more than a billion one-ounce organisms.

In the United States, escargot is what would politely be termed an “acquired taste”—one we’ve most assuredly failed to acquire. Even Vendetti hasn’t tried them. Despite the depressed national appetite, snail foragers have always lurked among us. (One helpful blog recommends “luring” snails in with oranges). But the real heroes of American escargot are farmers like Brewer, who have run headfirst into what’s arguably the strangest form of animal husbandry on Earth. Though it’s a dark, damp, do-it-yourself affair, they promise snail farming is not without its (slime-covered) charms.

Before you can eat a wild snail, you must starve it. Just as oysters are contaminated by dirty water, snails pick up the toxins around them, imbibing pesticides and heavy metals. Earlier this year, an Australian teenager who ate a slug on a dare contracted rat lungworm and died. The parasite hasn’t showed up in common snails, but Vendetti says, “absence of evidence is not evidence of absence.” To ward off illness, humans must handle any foraged food with care.

Brewer subjected his garden snails to a week-long “purging process” before he began breeding them. “Keep them moistened in a fairly warm environment, and that will ensure they’re digestively active,” he tells me, almost as if he’s dolling out directions. “Once they stop defecating, then you know they’re pretty well cleaned out.”

If this sounds cruel, it’s because it is. Farming anything other than alfalfa requires sacrifice. That’s particularly true when it comes to snails, because the creatures are considered pests by the U.S. Department of Agriculture, whose agents are therefore perplexed by the rare farmer who wants them to propagate. To the USDA, breeding escargot is like tenderly raising a plague of locusts. But because they’re snails—a-not-so-charismatic creature—the carnage can also be morbidly comical.

Related: Americans used to eat pigeon all the time—and it could be making a comeback

As you might expect, European garden snails are European. How exactly they got here is anyone’s guess, but it seems the brown helix has floated its way to every part of the world. It now thrives in New Zealand, South Africa, and across North and South America. In California, Vendetti says, “the story goes there was a man who moved here and missed escargot and snail mailed—no pun intended—no, wait, pun definitely intended—himself some snails.” A few escaped from their mesh, and bred rapaciously in the desert heat.

Their insatiable appetites quickly caused problems. C. aspersum eats cabbage, carrot, cauliflower, celery, bean, beet, brussels sprouts, lettuce, mangel, onion, peas, radish, tomato, and turnips. It eats barley, oats, and wheat. It loves flowers more than your mother on Mother’s Day. It crawls up the bark of apple, apricot, citrus, peach, and plum trees—and then eats them, too. “It is federally illegal to take a live snail across state lines,” Brewer says. “You can be fined, there’s potential jail sentences.” Even on the farm, keeping them fed is a struggle. “They go through quite a bit of vegetation,” he says. “Kind of the way a herd of cattle will eat all the grass in that area, and you have to move them.”

Taylor Knapp, owner of Peconic Escargot on the north fork of Long Island, New York, was one of the first snail farmers in the United States. He found that most escargot on the market was frozen and shipped in from Europe; finding something alive, or at least alive recently, was almost impossible. So he decided to go into business himself. “It was three long years of working with the government,” Knapp says, but eventually he helped to establish the USDA’s containment protocol for the entire species.

What looks like a greenhouse is actually Peconic’s elaborate gastropod prison. Groups of snails are stored in sealed, soil-lined crates. “It’s kind of like an indoor beekeeping operation,” according to Knapp, who gave himself the official title of “head snail wrangler.” The bins are shelved, turning a 300-square-foot greenhouse into a vertical maximum-security farm stocked with more than 50,000 snails. Should a snail escape from the sealed container, it will fall into a vat of concentrated saltwater, “which is kind of sad,” Knapp says. If it miraculously survived that assault, it would die outside: the greenhouse is surrounded by a non-vegetative perimeter, 12 feet by 12 feet, that Knapp laces with pesticides. “I basically just pick weeds all summer,” he says. “That’s my job.”

Once their snails are subdued, farmers hope for a love match—or several thousand. “Fortunately, snails are hermaphrodites,” Brewer says. Each snail can inseminate, and each snail can be inseminated and then lay eggs. The courtship ritual remains obscure, even to scientists, but it does involve those infamous “love darts.” If all goes well, one partner slides away with a clutch of 50 to 100 fertilized eggs.

Before a new generation can emerge, the eggs must be buried. “It’s kind of like a turtle,” Knapp says. “They burrow headfirst, using this special muscle to dig a hole into the soil… They’ll come back out of the hole, cover it in mucus and dirt, and then they’ll leave.” They never return.

The eggs, high in calcium, have a pearl-like finish. If the soil is right—loose and aerated, with a perfectly balanced moisture content—the eggs will incubate without drying out or swelling with water. Over a two-week incubation period, the snail inside doesn’t so much hatch as turn its smooth white bead into a mobile home. “If you watched a timelapse, you’d just start to see a spiral form on the outside of the egg,” Knapp says. “There’s nothing left over.”

It takes about six to eight months for each of Knapp’s snails to reach maturity, at which point they offer as much protein per pound as fish, and other essentials like iron and magnesium. “We know they’re as big as they’re going to get when they form this little lip on the edge of their shell that looks like a baseball cap,” he says. What size a snail is when it displays this lip varies widely—never a good thing in livestock. “Sometimes we end up with these teeny-tiny snails,” Knapp says, “and sometimes we end up with these monsters.”

Little Gray Farms has the same size problem, and Brewer is working to optimize his two-antennaed progeny. He recently secured USDA approval to move live snails across state lines, enabling him to introduce new and much-needed genes to the group. He also has a control population where he’s selecting the largest snails from each successive generation to breed, in hopes of growing bigger snails overall.

Peconic, for its part, is playing with taste. “We had a restaurant that asked for them to be finished on mint,” Knapp says. For the last two weeks of their lives, that’s all the members of the impending shipment ate. “When you ate this thing, the snail tasted like mint.” They’re also experimenting with snail caviar. The majority of Knapp’s eggs get to hatch, but some get salted. The eggs taste like the soil they come from: “earthy, mushroom-y, herbaceous,” Knapp says. “I think they taste like carrots.” Given they’re more shell than egg, they’re harder than other forms of caviar, like salmon roe, to burst. “You could roll them around in your mouth like bubble tea,” Knapp says.

Part of caviar’s appeal is that it’s easy to transport: just salt, pack, and ship. Escargot is more challenging. Peconic keeps its snails alive until a chef places an order. When the calls come in on Monday, Knapp kills the precise number of snails to fill the request on Tuesday, and the spoils arrive in cities across the country on Wednesday. This process, designed to guarantee the snail is fresh and the taste pure, means a shelf life of just seven days.

Most people still abhor the idea of eating snails, but maybe it’s nothing more than a PR problem. The flavor and texture of C. aspersum tends to hide beneath its preparation: like any Paula Dean recipe, most snails are served smothered in butter, so they mostly taste like butter. Even when prepared more plainly, escargot is similar to other, less frightening foods. It’s often described as having the texture of a clam, but denser, and with the ocean tang replaced by flavors of the forest. If that still doesn’t sell you on escargot, consider this: the snail’s class is “gastropod,” which (very loosely) translates to “portable food unit.” And what’s more American than that?