More than 1.2 million acres of the US have burned from wildfires so far this year. That’s roughly 500,000 acres more than the 10-year average—and across much of the West, peak fire conditions haven’t even set in yet. Currently, 11 large fires are burning uncontained in Arizona, Colorado, Florida, and New Mexico. And with much of the country in a deep drought, the rest of the spring and early summer are likely to look just as fiery, especially in the Great Plains and Southwest.

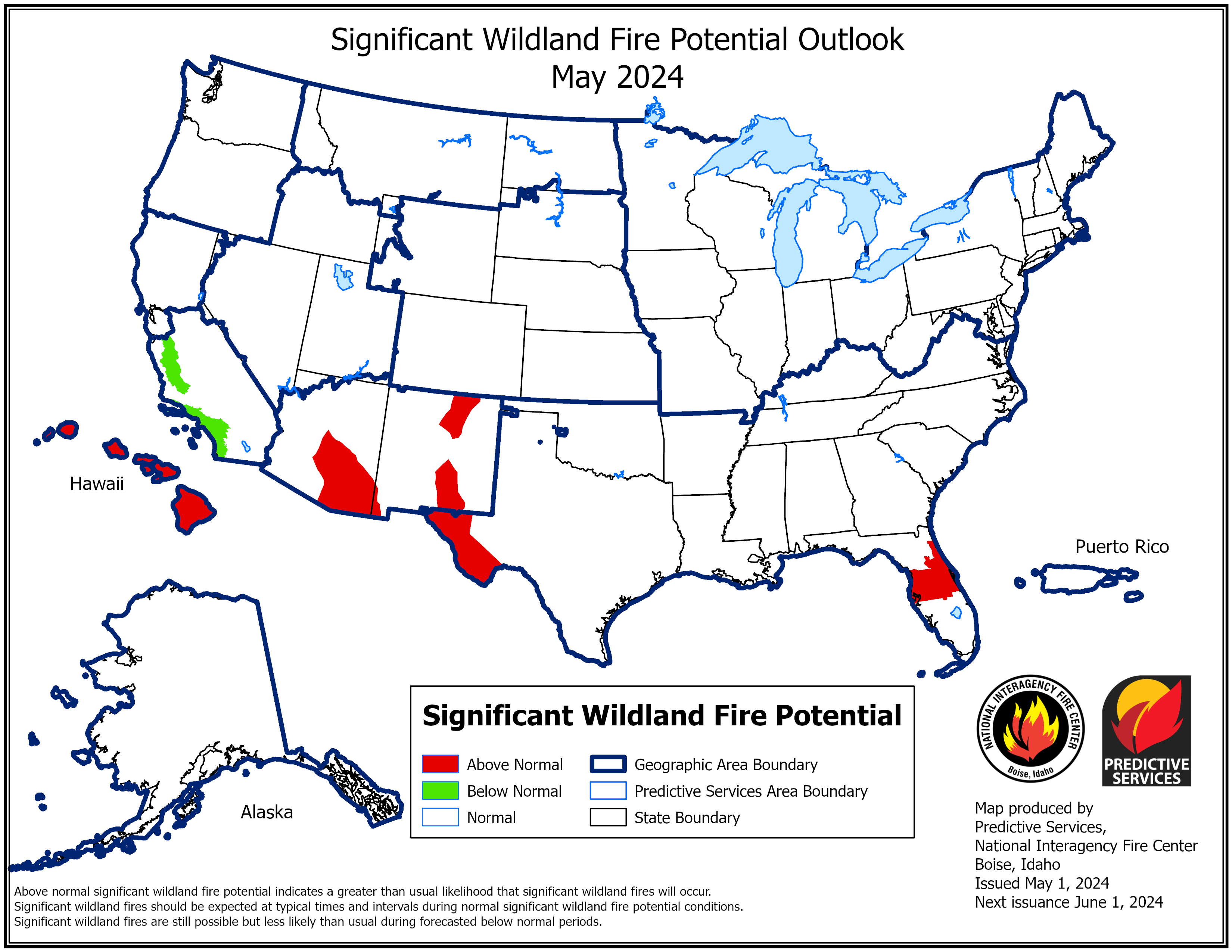

This year reflects a broader transition in fire behavior across the US, as hotter days and more variable rainfall have let a relatively concentrated “fire season” in the West turn into year-round disasters and risk. But the months of June, July, and August are still particularly fire-prone. On May 1, the National Interagency Fire Center (NIFC) released its predictions of fire weather through August.

[Related: Early US wildfires signal more spring infernos to come]

It’s important to note that the center can only forecast fire potential. “Whether you actually realize that potential is dependent on actual weather events,” says Jim Wallmann, a meteorologist at the NIFC. Windy days, lightning, and rain will all shape the actual season. “The bad news,” he says, is that during peak season will be “busy” from Wyoming to California.

Late spring

Right now, the US is very, very dry. The Mountain West, from California to the Rockies, is more than two decades into its most serious drought of the last 1,200 years, which has killed trees and left vegetation exceptionally fire-prone. Meanwhile, patches of extreme and exceptional drought through Arizona, New Mexico, and the southern Great Plains have set the stage for 2022’s biggest fires so far. One, on the eastern slope of the Rockies, has burned more than 160,000 acres, and is threatening the prairie town of Las Vegas, NM.

The outlook for the rest of May doesn’t look much better. The NIFC expects a normal monsoon season in the Southwest late June or early July that will wet grasses and end the most volatile fires. But until then, windstorms will continue to roll through the region as they have all spring, which spread new fires in open grasslands from Colorado to Nebraska.

The danger will also spread to the US-Mexico border as the month goes on. Last year, record-breaking monsoons hit southern Arizona and New Mexico. While that might sound like a good thing for fire management, it led to explosive growth of quick-drying vegetation, like invasive cheatgrass. As those dry out in the May heat, they’ll be more prone to carry fast-moving fires.

On the other hand, late-season frost and rain have momentarily tamped down on fire risk in the Pacific Northwest. Even though Central Oregon and much of Montana are locked in a drought, those weather patterns have kept fuel wet enough to stop blazes from taking off. Still, as temperatures grow hotter in the next few weeks, the NIFC believes that Central Oregon could be prone to rapid-growing fires driven by windstorms.

Early summer

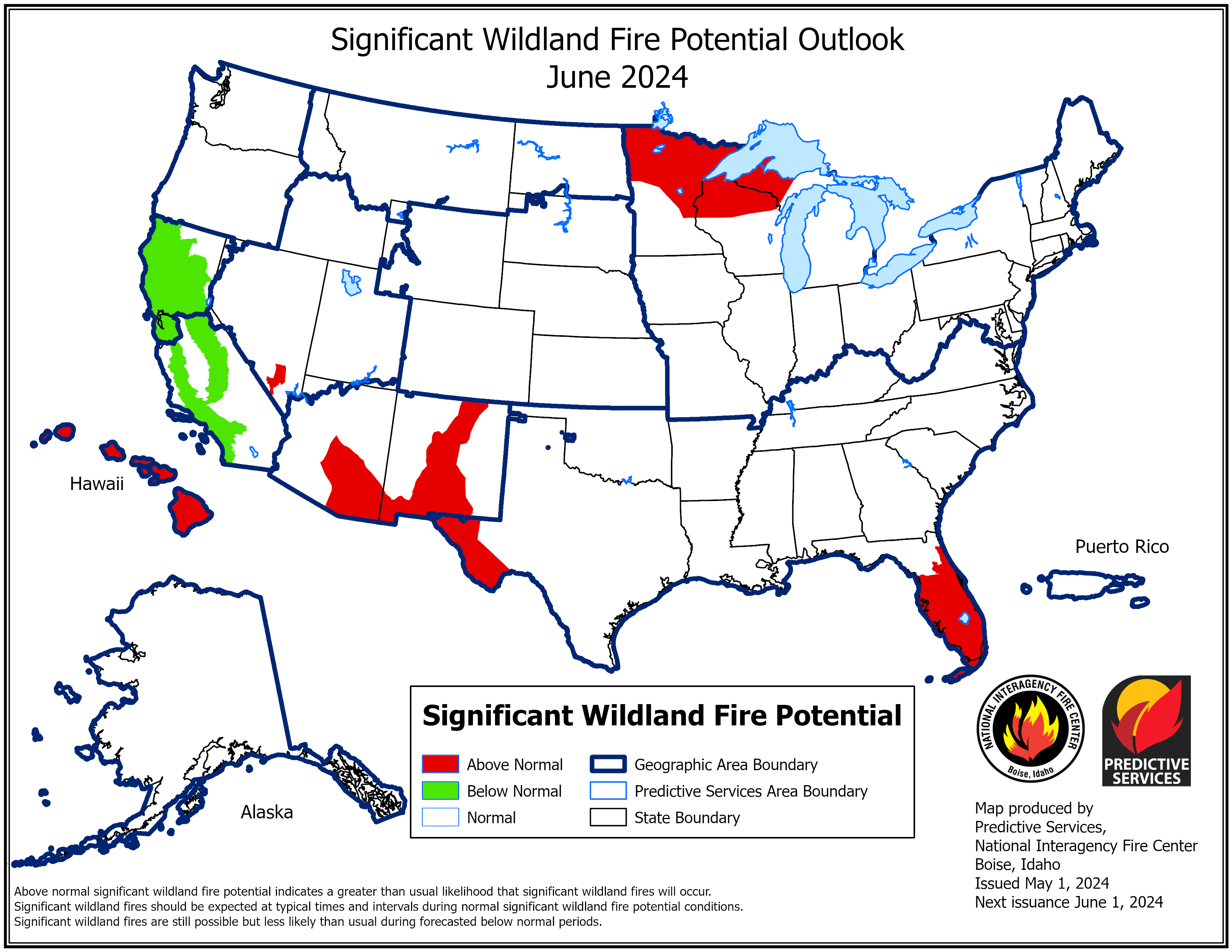

By June and into early July, fire danger will be much more widespread across the western US. In Northern California, early-spring plants are withering in an unseasonably hot spring. If a fire catches on a windy day, it would easily jump through the manzanita, chamise, and other woody shrubs in the hills from San Francisco to Sacramento.

The report also points to factors that could make fire season more unpredictable in California. In December, storms in the High Sierra blew down trees, which will dry out over the summer. That, combined with dead, drought-stricken stands, could fuel major fires, though the extent of that threat isn’t clear.

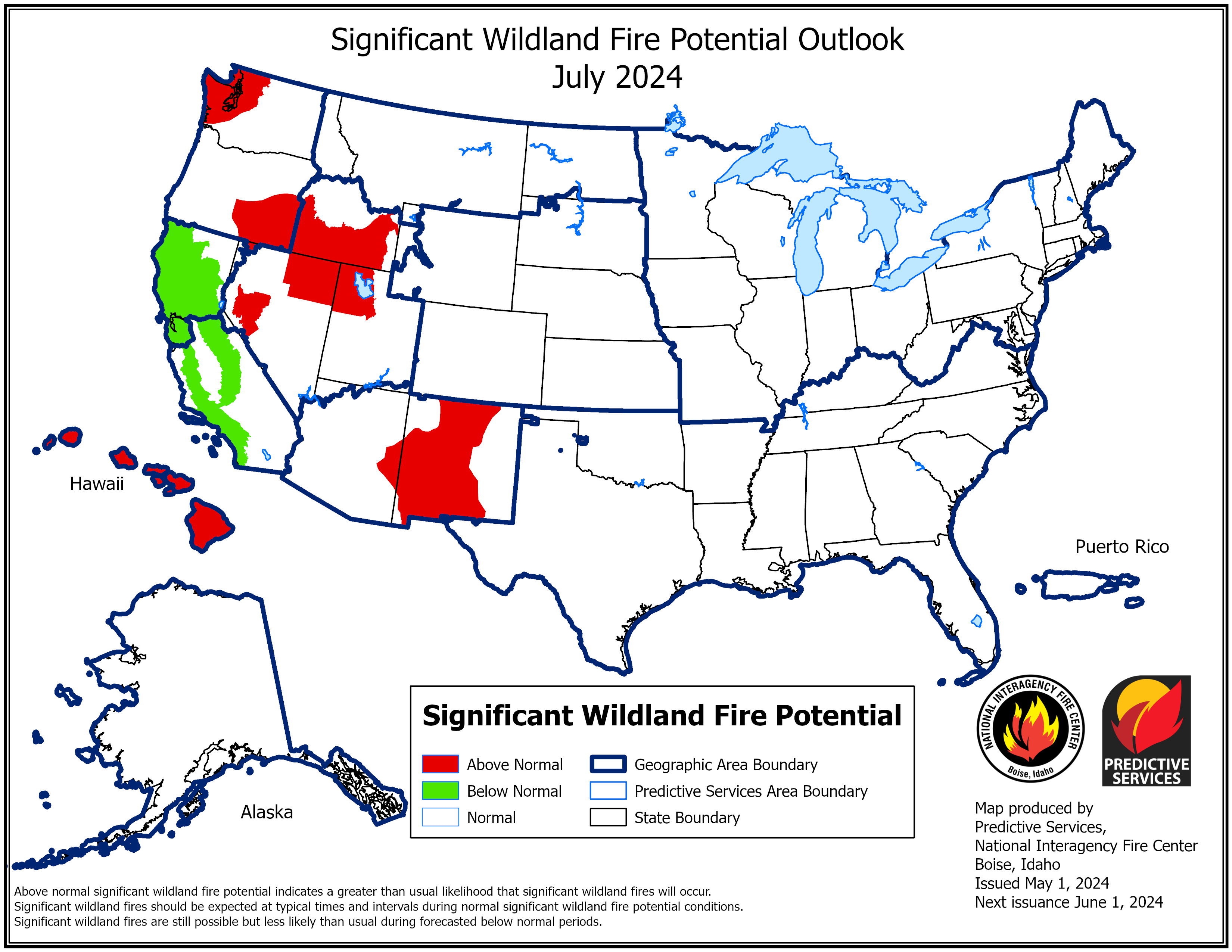

The Great Plains could be a hotspot as well this summer. The conditions that led to fires across Nebraska and Texas earlier in the year might stretch as far north as the Dakotas and east into Iowa and Missouri by July. “It’s not that unusual,” says Wallmann. “Things just do have to line up right. Last year, a lot of grass came up and there wasn’t much snow cover over the winter, so that grass is still standing.”

Late summer

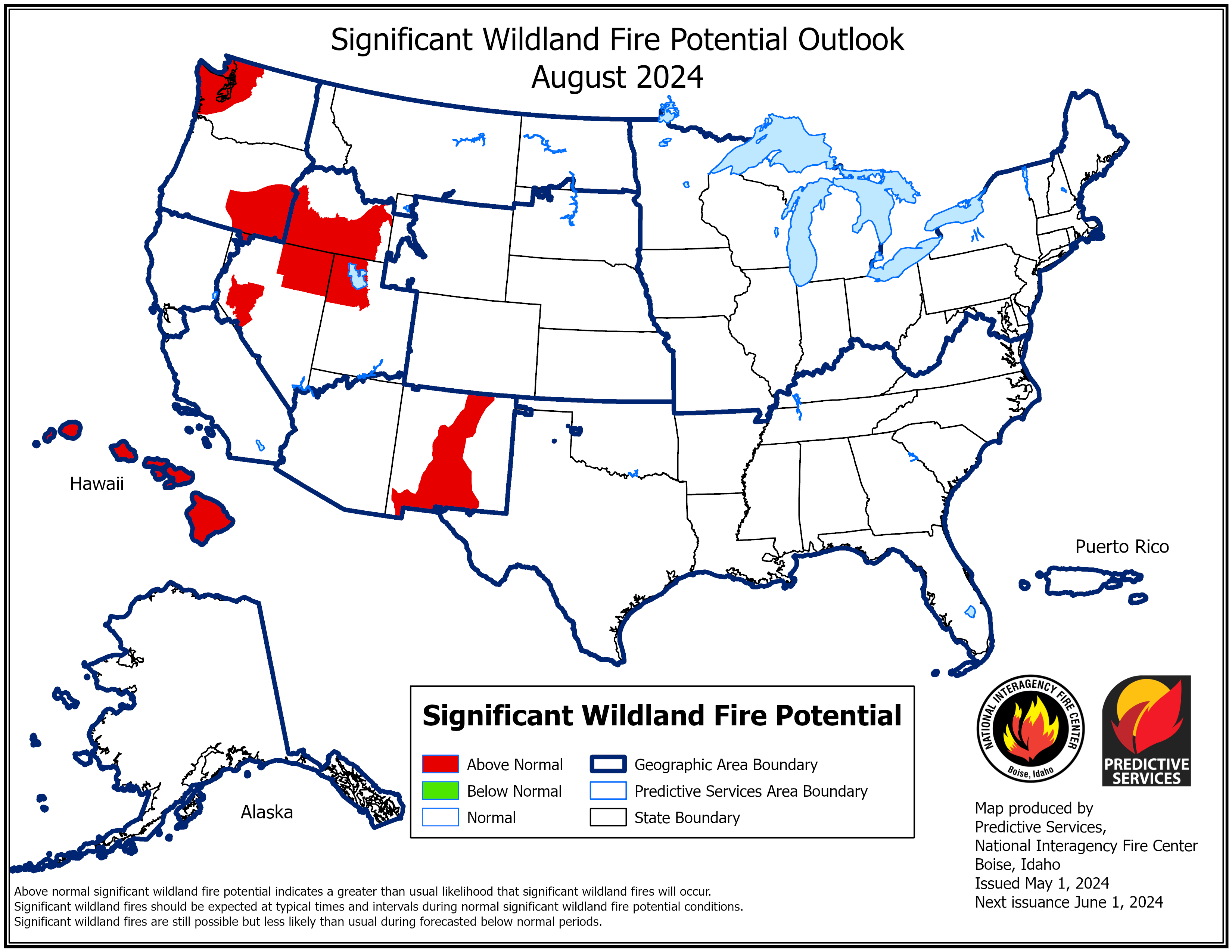

Once we reach mid-July and August, the fire danger starts to move across the US. Although much of the Midwest will remain at high risk, the beginning of the monsoon should bring relief for most of the Southwest and Southern Plains. (The rest of the plains will get some rain, but Wallmann says that in general, a heavy monsoon in the Southwest means less water further east.)

Fire danger will likely creep up across the Pacific Northwest, but the details are fuzzy. “As we get to August, there’s some uncertainty,” says Wallmann. In California, forecasters can draw fire-season projections fairly well based on the winter snowpack. But “as you go up north, a lot of the fire season is tied to what spring is like,” Wallmann explains. So while the NIFC is confident from local snowpack that Central Oregon and Northern California will be at high risk, it needs to watch the rainfall levels in May before predicting summer conditions in Northern Idaho and Montana.

[Related: Can you really use foil to fireproof your house?]

But based on data from the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, the NIFC projects that the region will see another summer that’s hotter than usual. At the same time, the high plains in eastern Oregon and Washington—an area where entire towns were destroyed by wildfires around Labor Day of 2020—will likely get less seasonal rains.

This year’s picture is better than 2020’s, Wallmann says, when summer monsoons just didn’t show up in the Southwest. Instead, he thinks 2022 looks similar to 2021. That said, last year marked three of the biggest documented fires in California history. Even a year that doesn’t break fire records can still stress firefighters and communities.