Over three million years ago, a 500-plus pound marsupial roamed Australia, winning the prize of the continent’s first long-distance walking champion. In a study published May 31 in the Journal of Royal Society Open Science, a team of scientists described the discovery of this new genus using advanced 3D scans and the partial remains of a 3.5 million year old specimen.

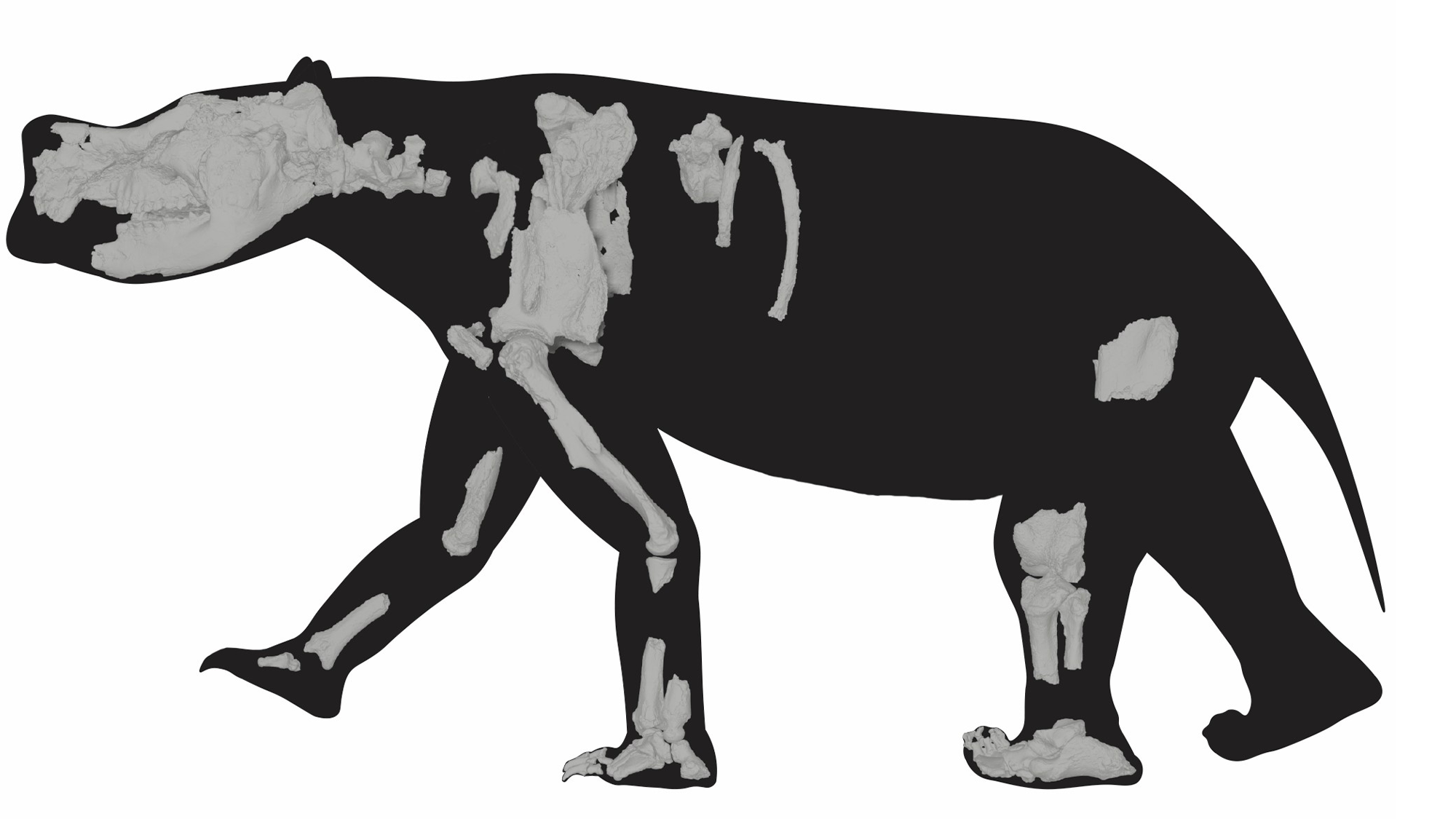

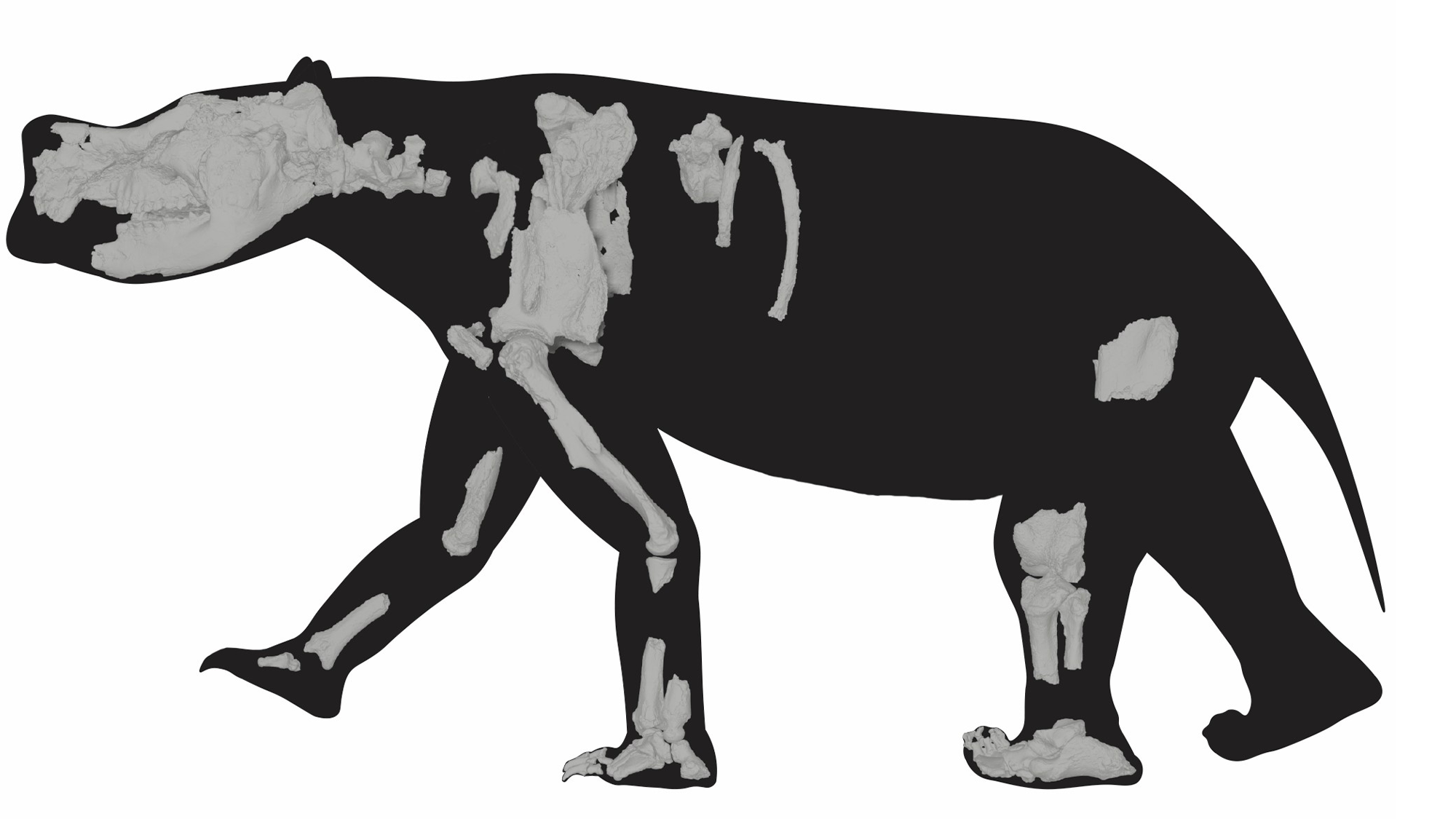

Most earlier studies on this group have focused on its skull since other skeletal remains are rare in Australia’s fossil record. The skeleton described in this new study, found at Kalamurina Station in southern Australia in 2017, is special since it is the first that was found with associated soft tissue structures. The authors used 3D-scanning to compare the partial skeleton with other diprotodontid material housed in collections all over the world. A hard concretion that formed shortly after the animal died encased its foot, and CT scans revealed the soft tissue impressions on the outline of its footpad.

[Related: Giant wombats the size of small cars once roamed Australia.]

The new genus Ambulator, meaning “walker” or “wanderer,” had four giant legs which would have helped it roam long distances in search of food and water compared to its earlier relatives. It belongs to the Diprotodontidae family, an extinct family of big, four-legged, herbivorous marsupials that lived in New Guinea and Australia. The largest species was Diprotodon optatum, which was about the size of a car and weighed almost 6,000 pounds. Diprotodontids were an integral part of the region’s ecosystem before going extinct about 40,000 years ago.

“Diprotodontids are distantly related to wombats – the same distance as kangaroos are to possums – so unfortunately there is nothing quite like them today. As a result, paleontologists have had a hard time reconstructing their biology,” study author and Flinders University PhD student Jacob van Zoelen said in a statement.

Ambulator keanei lived during the Pliocene era when Australia saw an increase in grasslands and open habitats become more dry. To have enough to eat and drink, diprotodontids likely had to travel great distances.

“We don’t often think of walking as a special skill but when you’re big any movement can be energetically costly so efficiency is key,” said van Zoelen. “Most large herbivores today such as elephants and rhinoceroses are digitigrade, meaning they walk on the tips of their toes with their heel not touching the ground. “

Diprotodontids are plantigrade animals, which means that their heel-bone makes contact with the ground as they walk. This is similar to the way humans walk and helps distribute the weight while walking, but does use more energy when running. According to van Zoelen, diprotodontids also have extreme plantigrady in their hands. The bone of the wrist is modified into a secondary heel and this “heeled hand” may have made early reconstructions of the animal look a little bit bizarre.

“Development of the wrist and ankle for weight-bearing meant that the digits became essentially functionless and likely did not make contact with the ground while walking.” said van Zoelen. “This may be why no finger or toe impressions are observed in the trackways of diprotodontids.”