No two fads are growing faster than getting fit and going green. Is it possible that by achieving the former, one could also accomplish the latter? Harnessing human movement has long been a holy grail of renewable energy, but real-life implementations have been relegated to advertising stunts and commercially impractical gadgets. But ReRev.com, a startup company from St. Petersburg, Florida, thinks its technology can let us improve our own health, and that of our planet, by working up a sweat.

The ReCardio system retrofits standard exercise equipment to capture energy from the machine and send voltage directly back to the utility grid. An installation in Gainesville on 15 elliptical machines has already created more than 200 kilowatt-hours without a minute of required maintenance. Progress Energy, a Florida utility company, agreed this week to split the bill with the University of Florida for installations on 40 machines, with the potential for more. Displays at each machine will show every watt generated by your lunchtime workout, while a website will provide real-time numbers on the total watts saved by the installation. ReRev.com has its eye on megagyms in Las Vegas and Miami that could “essentially be giant GE turbines,” says CEO Hudson Harr, age 22. Conversations with “major chains” are ongoing but nothing has been solidified to date.

Sapping power from workout machines isn’t new. Fans of “The Biggest Loser” or Amp energy drinks will remember gimmicks that powered lights with some human pedaling. A handful of gyms in Japan even retrofitted machines with energy-sucking technology. According to Harr, what makes ReCardio different–and commercially viable–is that it doesn’t feed energy into a battery, but instead pumps directly back to the utility grid.

According to Harr you lose 50 percent of the energy you create when you pass it through a battery. So instead of producing 100 watt-hours in your workout, you only make 50 watt-hours. Besides their inefficiency, batteries cost more, require maintenance and space, and have a greater safety risk than the ReCardio design. The number of batteries must also increase if you want increased output, whereas the ReCardio system has no upper bounds. The specifics of how ReCardio avoids using a battery is at the heart of ReCardio’s patent applications, but Harr isn’t ready to share details.

Each retrofitted machine has a controller box that feeds into the central ReCardio processor and finally into an inverter that taps directly into the building’s electrical system. Any elliptical machine could create up to 300 watt-hours of energy after a retrofitting that costs approximately $300 per machine (the cost would decrease with big orders, and additionally would be offset by big tax credits). At one dollar per watt-hour, that makes the system significantly cheaper than solar power, which can cost $10/watt-hour. For a given machine, about 100 watts are generated for an average hour of usage (depending on the specific machine and intensity). Ten hours of usage creates enough power to charge your cell phone 397 times, or the equivalent of the battery of a 2004 Prius. Based on usage in the current installations, Harr says that a $5,000 ReCardio installation would pay itself off in half the time of an equivalently priced solar installation.

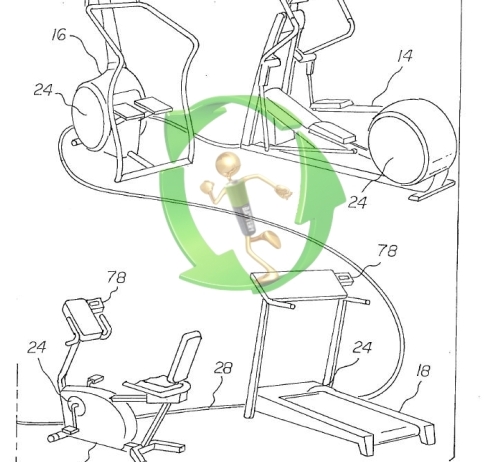

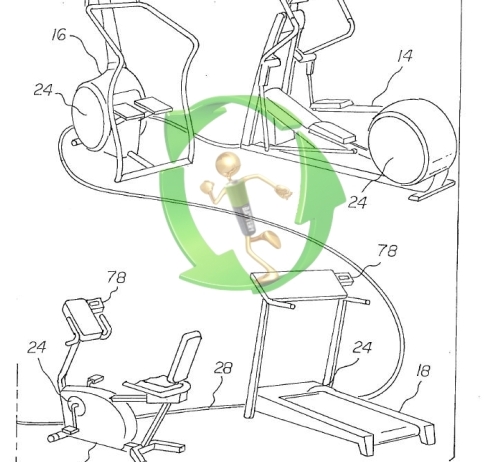

Current installations are focused on ellipticals, which Harr calls “low-lying fruit.” Because of their gear ratios and small amount of moving mass they offer the best output, but ReRev.com also retrofits bikes, rowers, treadmills, and stair climbers. While the technology is technically feasible for home use, Harr says, for now a cluster of 10-15 machines is necessary to justify the required infrastructure.

If the machines run while not attached to the system, the excess energy produced is burned off in the form of heat that requires air conditioning systems to work overtime. Harr believes the financial advantages of eliminating this are equally impressive, but has yet to crunch any numbers.

Perhaps counterintuitively, Harr also says the power created by the machines is more consistent than solar or wind power. While a cloudy day will limit what a set of panels can provide, gym rats are nothing if not predictable.

“We know they work out less on Fridays and then more on Monday because they’re guilty after the weekend,” said Harr. “If they don’t go on a Tuesday they’ll make up for it on Wednesday. So your aggregate numbers are really consistent.”

With 24-hour gyms all the rage, power could be produced around the clock. Despite the apparent advantages, Harr recognizes that there are only so many gyms nationwide; he sees ReCardio as just one piece of the puzzle.

“We’re absolutely not trying to beat solar. I love solar,” said Harr. “I think the key is a mix of as many renewable sources as possible.”

Harr stresses that this isn’t just a demonstration to show fourth graders how power is produced, or why we should turn off our lights when we go to bed. “We’re in commercialization. Our suppliers are ready to order and we can put this technology in as many locations as possible. We’re ready to rock here.”

Hmm. Guess it’s about time for a new gym membership.

Got a question? Have a tip? Submit new research, technology or questions about all things sports & science to zarda13@yahoo.com.