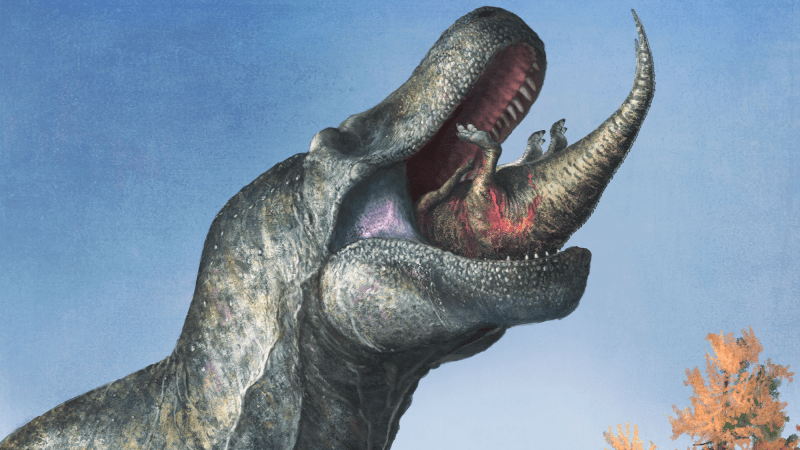

Let’s go back 160 million years to the middle of the Jurassic period. The world was a temperate forest: a leafy wilderness full of giant ferns and ginkgos, with conifers (the family of cone-bearing trees) and palm tree-like cycads. Land was home to a menagerie of dinosaurs, amphibians and even some of the oldest, now-extinct mammals.

When you think of the Jurassic sky, you might imagine screeching, winged pterosaurs. But they likely shared their airspace with smaller, furrier creatures.

A team of paleontologists from the University of Chicago and Beijing Museum of Natural History found proof of ancient gliding mammals in unexpectedly intact fossils from the time of the dinosaurs.

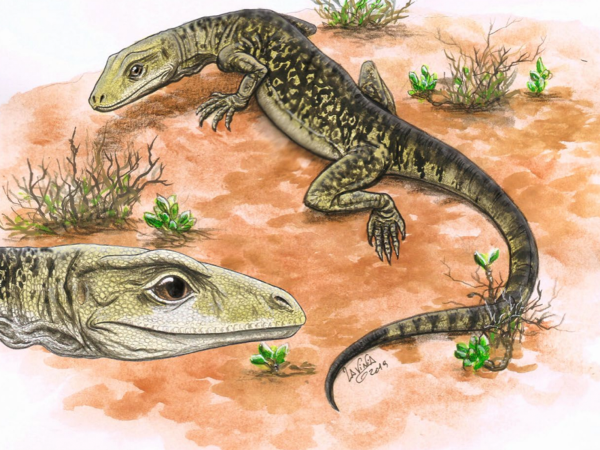

The two fossils in question are of Maiopatagium and its smaller counterpart Vilevolodon. They are considered to be haramiyidans, early mammals that went extinct during the mass extinction at the end of the Cretaceous period that brought about the demise of the dinosaurs and most of the life on Earth.

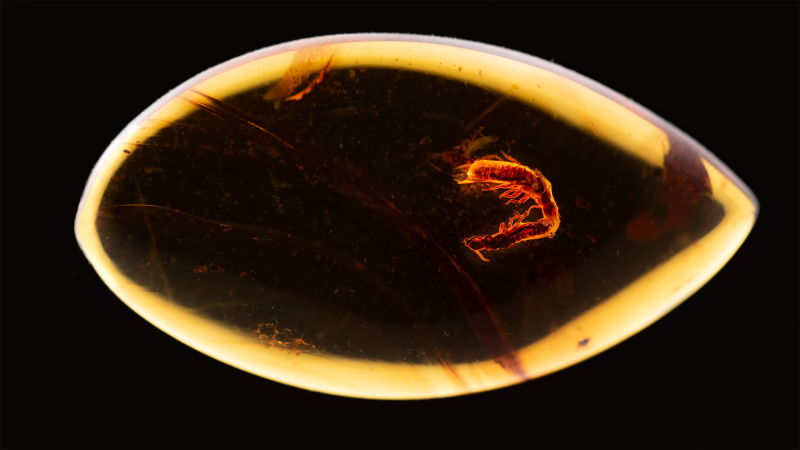

Maiopatagium and Vilevolodon were found in the same rock formation in northeast China, where the fine sediment of a shallow Jurassic freshwater lake preserved them in excellent condition. “These are some of the most beautiful fossils that I’ve ever seen,” says Zhe-Xi Luo, senior author of the study and a professor at the University of Chicago.

These incredibly well-preserved fossils retained many fine details, including fur-covered membranes that formed a wing-like connection between the front and back legs. The fossils also showed that the bones in forelimbs were proportioned similarly to the bones in other known gliders, and the shoulders were seemingly designed to maximize mobility—a must-have for being able to glide through the sky on extended arms.

In 2007, a separate set of researchers also found a fossil in northeastern China with membranes for gliding. They estimated that the animal was alive 125 million years ago. But this more recent discovery pushes the timeframe for the evolution of gliding among mammals back by 35 million years.

If you managed to travel back in time, and looked to the Jurassic sky, you might have seen Maiopatagium and Vilevolodon gliding between trees. It’s not quite flight, at least not the way that we think of it: Unlike birds, or even bats—another airborne mammal—these early mammals did not have powered flight. But the ability to glide is still an important adaptation. We still see it in some mammals, like flying squirrels and sugar gliders.

“To glide and take into the air is an inspirational feature for some mammals,” Luo says.

Back when Maiopatagium and Vilevolodon walked—or glided above—the earth, they were probably tree-dwelling herbivores, like their haramiyidan relatives. A second study published by the same group this week shows that the fossils’ mortar and pestle-like teeth appear to be specialized for a herbivorous diet of crushing and grinding soft plants and seeds.

The ability to glide is thought to evolve so that these tree-dwelling animals can efficiently explore food sources scattered among the trees. After all, which is easier: climbing down from your tree, walking through the underbrush (which could be home to any number of predators) and climbing up another tree; or just gliding from one tree to another?

Being able to glide would have kept these two species out of reach of ground predators, while giving them easy access to their food sources. It’s the same reason that some modern-day tree-dwelling mammals evolved the ability to glide, Luo says.

But modern-day gliding mammals actually evolved completely separately, almost 100 million years after the early gliders. After all, haramiyidans were wiped out by the mass extinction (and if the dinosaurs didn’t make it, these small mammals didn’t stand a chance.) As Luo points out, you can see the same pattern repeating itself over and over throughout the history of evolution: “Ground to tree, then tree to air.”

“[Maiopatagium and Vilevolodon] come from one of the most ancient lineages of fossil groups, long before the rise of modern mammals,” Luo says. “They did their own evolutionary experiment to glide.”

P. David Polly, a professor of geological sciences at Indiana University who was not involved with this study, says these findings show just how specialized early mammals were, comparing their complex adaptations to the way that modern species have evolved and coexisted in modern rainforest.

“We need to completely rethink the community structure and ecological relationships of the Mesozoic, especially with regards to how mammals fit into it,” Polly says.