There are few better ways to learn about how computers work than by building one from scratch, and few better excuses to snap fresh, solder-scented boards into waiting ports, if you’re one to enjoy such things. But if you’re primarily a Mac user like me, the call of that great geek rite of passage may have as yet gone unanswered; homebuilt PCs can’t run OS X natively.

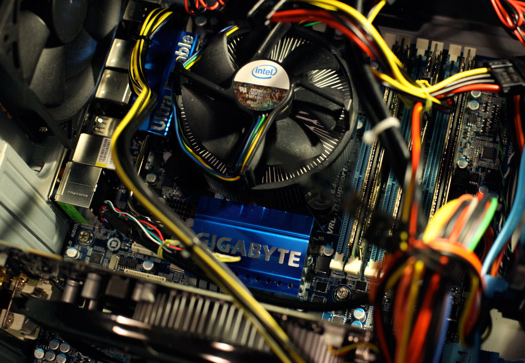

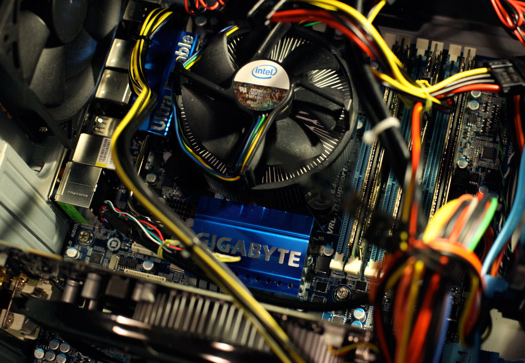

But listen here, Mac geeks. Thanks to the efforts of an increasingly active online community of developers, building a Hackintosh–a PC built from components that runs OS X like a charm–has never been easier. And by choosing your own hardware, it’s entirely feasible to rival the specs of a brand-new Mac Pro for around half the cost.

This week, over the course of three articles, I’m going to show you exactly how easy building and configuring your own Hackintosh can be.

Somewhat ironically, considering some may build a Hackintosh to avoid visiting the Apple store, this project all started for me after I bought a new 11-inch MacBook Air. After parting with our loaner unit upon publishing our review, I knew I wanted one to replace my comparatively beastly MacBook Pro. But as we pointed out, the 11-incher is best suited as a mobile complement to a more powerful home computer with a bigger screen. To me, it didn’t make much sense to have my primary home machine also be a laptop that never left my desk–especially when the bill of materials for a custom-built PC plus the new MacBook Air didn’t total much more than a top-of-the-line new Apple laptop.

In my review, I alluded to the possibility that it might be time for me to build a Hackintosh desktop to serve as a compliment to my new Air, so after selling my 15″ laptop, that’s what I set out to do.

I haven’t used a desktop computer regularly since my parents’ Packard Bell in the early 1990s, but more and more it makes sense to have a powerful, always-on, easily expandable (and capacious) machine acting as a file and media server for the ever-growing number of web-connected gadgets in your home. There are plenty of things to surf the web on from the couch these days—your phone, your iPod touch, maybe a tablet, or your MacBook Air for that matter—so with that need taken care of, the advantages of a desktop machine at home become even more clear.

A Hackintosh fills this need perfectly, with a power-per-dollar ratio that’s considerably higher than any Mac you can currently get from the Apple store, laptop or desktop. And lucky for us, a vibrant community and an exceptionally well-developed set of install tools called MultiBeast has made the Hackintosh process easier today than ever; if you’re comfortable enough to build your own PC from parts, you can handle the software install too. I’m by no means a solderer or a programmer, and I was able to.

For this we owe huge thanks to the folks at tonymacx86.com, authors of MultiBeast. It’s the de facto method right now for installing OS X 10.6.x on PC hardware. Over the course of three articles, I hope to cover the current, well-developed state of the Hackintosh scene and point you toward plenty of information and resources to build one yourself. Today, I’m going to cover the basic concepts and show you where to start poking around to learn more; stay tuned tomorrow and Friday for parts two and three, where we’ll select our hardware and put the thing together, then install and configure OS X (and maybe even install a copy of Windows 7 for dual booting). So, let’s begin.

Hackintoshing: A Primer

Like any nerdy pursuit that involves lots of forum-hunting, building a Hackintosh is so much easier when you have some grasp of the basic concepts involved, no matter how complex and abstract they may seem. Once you begin to pick up the language spoken within, you’ll find the forums surrounding the various Hackintosh communities to be incredibly valuable tools for learning and troubleshooting.

My most valuable resource in this process was by far the forums, wiki and blog posts on tonymacx86.com. Tonymac’s compatriot and co-developer MacMan, who is now the primary developer of MultiBeast, also maintains an invaluable blog, as well as the install guide I used for my machine. In speaking with both Tonymac and MacMan via email for this article, it’s clear that both are extremely nice fellows (or ladies! you never know) who are dedicated to their project above all. The forums are friendly and welcoming for the most part, which is certainly not always the case with such places. Tonymac takes voluntary donations, but otherwise, both of them appear to be in it for the non-fiduciary mix of renown, bragging rights, dedication and pure curiosity that drives many of the best open source software projects.

Elsewhere on the web, the forums at insanelymac.com are also very much alive with Hackintosh folks, many of whom help maintain the very handy OSx86 wiki. And beyond these, many other communities (and install methods) abound, but Tonymac’s MultiBeast is what we’ll cover here.

The Basics

Individuals, as well as companies like Dell and HP, have been using component PC hardware to build Windows and Unix-based computers for centuries (in computer years). So long, in fact, that the phrase “IBM Compatible” is still sometimes used to describe this class of machine, long after IBM sold their personal computer business to Lenovo. This is because the archetype can be traced all the way back to the original IBM PC–an Intel machine that ran DOS, the command-line OS that served as the foundation for Windows.

As the IBM Compatible Wikipedia page sagely points out, even though the power of today’s computers would have seemed wholly inconceivable to most IBM PC users in 1981, a remarkable level of backwards compatibility remains. That’s because the foundational structure of a Windows PC has not significantly changed in 30 years.

The relevant legacy bit here for us is the BIOS–the software pre-loaded onto a PC’s motherboard that’s responsible for recognizing installed hardware and launching the operating system. The basics of the IBM Compatible BIOS haven’t changed much since the early days. Which is why it’s easy to throw together a Windows PC from a variety of different parts from hundreds of different manufacturers.

Apple computers have always worked a bit differently than Windows PCs at the BIOS level. Before Apple’s 2006 switch to Intel, the main difference was Apple’s unique Motorola/PowerPC processor architecture. And then, following the switch to Intel processors in 2006, Apple elected to go with a more modern BIOS-like system called the Extensible Firmware Interface (EFI) which isn’t directly compatible with the legacy BIOS pre-loaded on almost all Intel-based PC motherboards. So even though the hardware inside your Mac Pro, from the Intel processor to the Nvidia graphics card, could be exactly the same as parts found inside a Windows PC, the two operating systems remain incompatible at the BIOS level. OS X is designed only for Apple-made EFI-based systems, so it won’t install natively on your generic home-built PC.

So the first step in any Hackintosh configuration is tricking the OS X install disc into installing on a machine that doesn’t have EFI. In the MultiBeast method I’m covering here, this first trick is accomplished by a burned boot CD called iBoot, which does the emulation and sleight of hand necessary for your plain-old store-bought Snow Leopard install disc to think it’s inside the friendly confines of an EFI-based system.

Once Snow Leopard is installed, there’s still a fair amount of tweaking necessary if you want the machine to boot without the help of your magic CD and have all its hardware natively supported. Hardware support is handled by installing and configuring the necessary device drivers (called kernel extensions, or “kexts” in OS X parlance) for everything from your video card to your on-board audio chipset.

In the method we’ll be using, this second step is covered singlehandedly by MultiBeast, a handy Mac application that bundles and installs the large number of necessary drivers and kernel extensions a Hackintosh might need. In addition, MultiBeast installs a special bootloader called Chimera, which sits between the PC’s BIOS and the operating system and has a lot of hardware recognition built-in. Chimera also allows you to boot straight into OS X (or any other OS you have installed, as you’ll soon find out) without the help of your iBoot CD.

Still with us? If not, don’t worry. We’ll go into more detail in the next two installments. The good news is that all of this software is free, and unlike many other hack-y apps of its kind, it’s very well-designed for maximum ease of use. You’ll see.

Coming up tomorrow is a guide to choosing your hardware components—probably the most important (and potentially confusing) step in the entire process. From there, we’ll put the whole thing together, install OS X, and configure everything for maximum performance. It’s going to be great.

The Fine Print

But before we begin, a word of caution. Apple is, legally speaking, not a fan of this process. Installing OS X on non-Apple hardware is a violation of the license agreement. In the past, setting up a Hackintosh potentially involved an illegally pirated and tweaked OS X install disc, which was even less savory. But now, most current processes work with an officially purchased OS X 10.6 disc, which is obviously preferable.

So there’s that. But this is still a “proceed at your own risk” scenario, despite a fairly uncontentious environment currently. As Tonymac told me via email, “Sure, it’s always a possibility that Apple finally gets fed up with the scene and pulls the plug. But after almost five years of Intel Macs and the scene developing I don’t think that’s a real possibility at this point.” Knock on wood. He also makes the good point that the Hackintosh process will by its very nature bring more people to the Mac platform, and while I think the process will be fairly easy for you, PopSci reader, it’s still a bit too complex to make anything resembling a tiny dent in Apple’s hardware sales bottom line. But, as with anything hack-y, proceed carefully and be prepared for the potential that a software update from Apple could end the whole party.

So with that out of the way, I hope you enjoy our series. Happy Hackintoshing!

Check out part two of the series on choosing and assembling your hardware here.