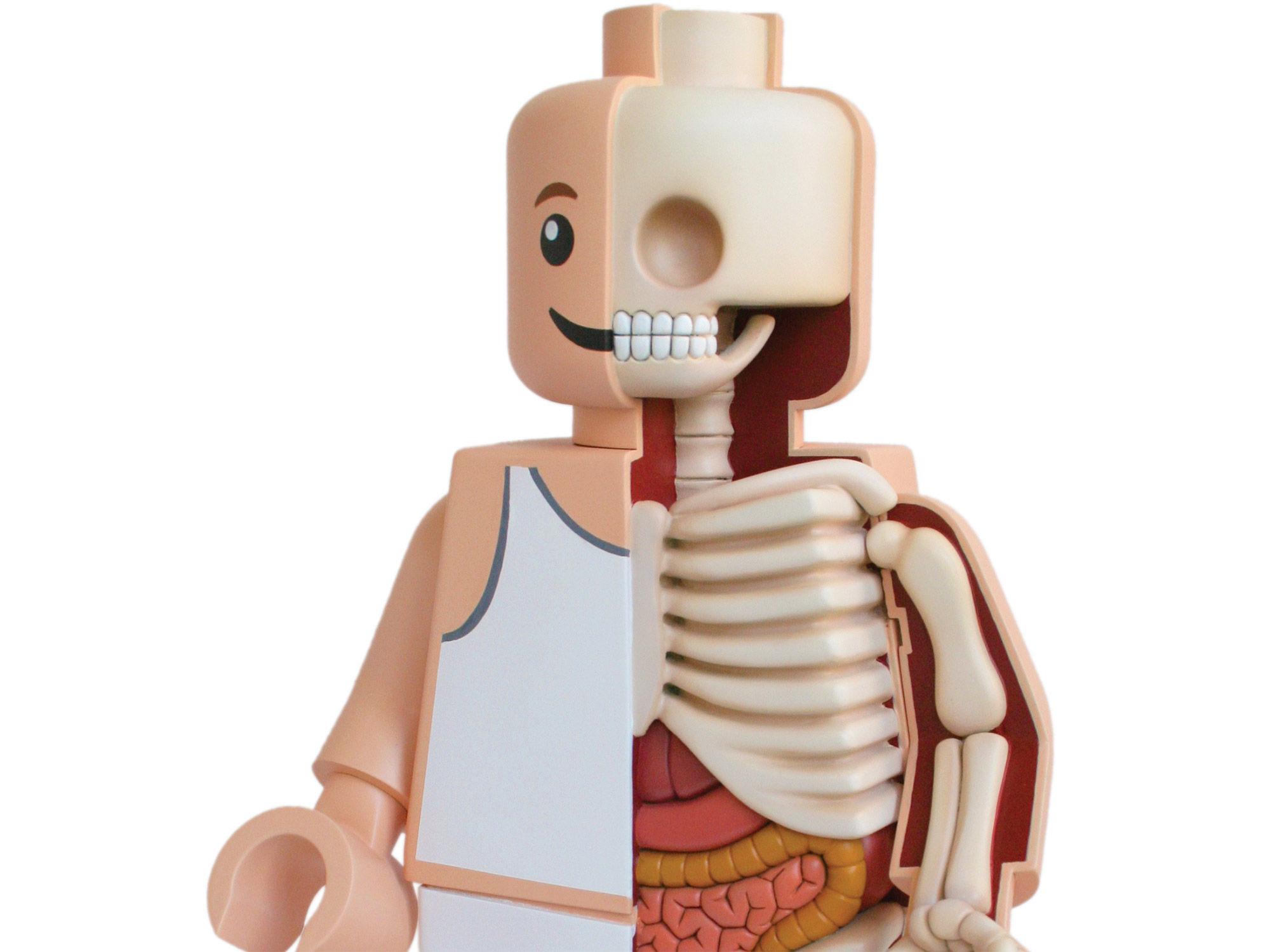

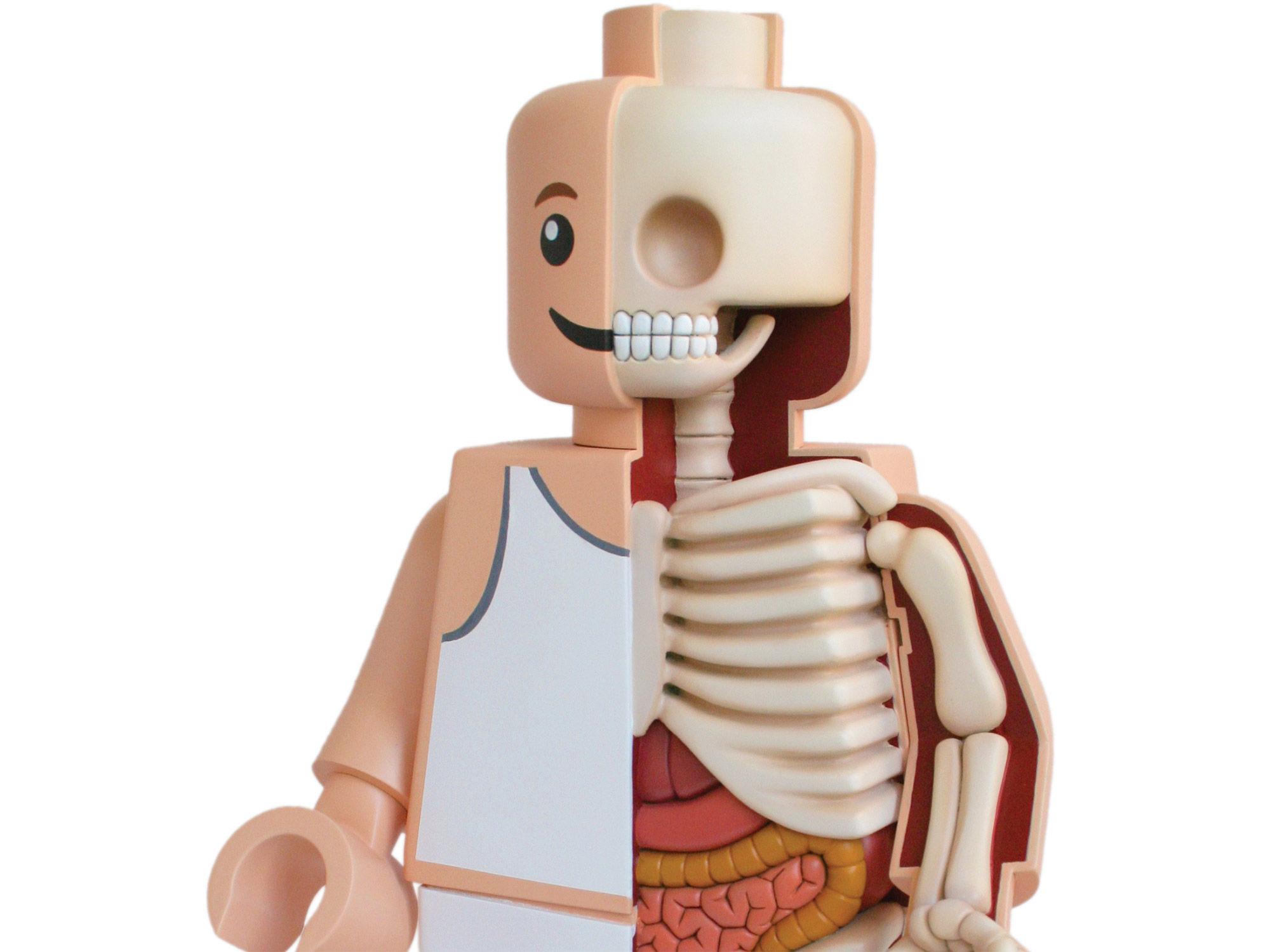

Chronic stress stems from many circumstances, such as poverty, a bad marriage, or long-term ailments. Its repercussions—elevated cortisol levels and inflammation—can wear us out, from the cellular level on up to our major biological systems.

Nervous System

The brain changes in response to experiences and the environment. This is especially true in childhood, when key structures—such as the amygdala, involved in the fight-or-flight center—develop. Extreme childhood adversity can alter these structures and impact mental health later in life. An estimated 30 percent of anxiety disorders are linked to early trauma. Research from Columbia University shows that orphans who spent their early years in institutional care can have abnormally large amygdalae, physical changes that can persist even after adoption.

Cardiovascular System

Both chronic stress and stress-related disorders, such as anxiety and depression, increase the risk for heart disease, although scientists are not entirely sure why. According to the American Heart Association, stress may indirectly influence cardiovascular health through high blood pressure as well as unhealthy behaviors, including overeating and smoking. And the shock of sudden, intense stress, such as the death of a partner, can rapidly weaken the heart, possibly because of a surge of stress hormones. The phenomenon is called broken heart syndrome.

Digestive System

The brain and the digestive tract are in constant communication, says Emeran Mayer, a gastroenterologist at UCLA. Unsurprisingly, chronic stress is associated with painful gastrointestinal issues. According to Mayer’s research, some patients with irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) show abnormal levels of cortisol and cortisol-stimulating hormones. People with IBS are also more likely to suffer from stress-related psychiatric disorders, including anxiety and depression.

30: Percent of U.S. adults who say stress strongly impacts their physical health; 33 percent say it strongly impacts their mental health

Cells

Nearly every cell has chromosomes, and the tip of each one is capped by a bit of genetic material; each time a cell divides, these telomeres shorten. When they run out, the cell dies. The chronically stressed have unusually short telomeres, putting them at risk for many age-related illnesses. The effects can be dramatic: In 2014, researchers found that disadvantaged 9-year-old boys had telomeres 19 percent shorter than those from more stable environments.

Immune System

According to research by Janice Kiecolt-Glaser, a clinical psychologist at the Ohio State College of Medicine, vaccines are less effective when we’re stressed and wounds take longer to heal. Research from Carnegie Mellon University shows that stress even makes us more vulnerable to the common cold. In 2012, the scientists found a likely culprit: In a healthy body, cortisol helps suppress inflammation. But the chronically stressed have consistently elevated cortisol levels, so the immune system grows resistant to the hormone, effectively ignoring it. Inflammation-causing proteins called cytokines—associated with developing a cold—then go unchecked.

Metabolic System

High cortisol levels boost the amount of fat around the belly. Extra abdominal fat may increase the risk for diabetes, which in turn may impair the stress response in the brain, says Antonio Convit, a psychiatrist at the Nathan Kline Institute for Psychiatric Research. The system that inhibits cortisol in the brain doesn’t work normally in people with type-2 diabetes. These patients also have blunted levels of cortisol when they wake up in the morning, as well as damage to the hippocampus, a brain region with concentrated cortisol receptors that is especially vulnerable to chronic stress.

How Does Stress Mess With Your Sleep?

The stress hormone cortisol helps regulate sugar levels in the body. Cortisol levels vary throughout the day, but typically follow a circadian rhythm where they are highest in the morning, drop steadily, and then build up again overnight. Researchers from the National Institutes of Health found depressed patients tend to have abnormally high cortisol levels. Scientists still don’t know what this means, but it points to one of the many ways that stress-related disorders may interact with and disrupt normal body cycles.

This article was originally published in the March 2015 issue of Popular Science, as part of our “Science of Stress” feature. To find out more about stress and how to beat it, read on.