Imagine walking into a hospital nursery full of pre-term babies and seeing not incubators, but bags full of fluid with infants tucked securely inside. It’s not a far-off science fiction fantasy: on Tuesday, researchers announced unprecedented success in keeping sheep fetuses alive within an “artificial womb” apparatus. The results are incredible. But what do they mean for humans?

Bye bye uteri?

First things first: while this artificial womb is futuristic as hell, it’s not meant to replace a good old-fashioned uterus. And this isn’t a sign that we’re getting close to totally artificial gestation. Back in 2014, futurist Zoltan Istvan predicted that “ectogenesis”—a.k.a. gestation minus a biological womb—would exist in just 20 years, and be widely used in 30. Such technology, he and many others argue, would allow for safer, more controlled pregnancies (for both fetuses and mothers) and would take the childbearing onus off of individuals biologically equipped to carry pregnancy.

Potential controversies abound, of course. How do abortion laws that hinge on viability—the point at which a fetus could survive outside the womb—change when a fetus could technically survive outside the womb at any point? How do parental rights change? What if babies miss out on unknown benefits of womb life, be they psychological, microbial, or of some other nature?

Luckily, we don’t have to think about that just yet. For now, the ins and outs of the earliest days of gestation remain too complex and mysterious for researchers to successfully rear a fetus from zygote to viability.

“The reality is that at the present time there’s no technology on the horizon,” lead study author Alan Flake of the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia (CHOP) said at a press conference on Monday. “There’s nothing but the mother that’s able to support that period of time.”

So what is it for?

Researchers weren’t going after the golden stork of totally womb-less reproduction. Instead, they were trying to find a way to save babies who currently have some chance of survival—but not much.

One in ten U.S. births are premature (younger than 37 weeks gestational age—full term is 40 weeks) and improvements in neonatal medicine have made this less and less of a problem. But that means there’s a new, growing category of babies who survive “critically preterm birth”—delivery before 26 weeks of gestation. Babies in this category now have a 30 to 50 percent chance of survival, but have a 90 percent morbidity rate, meaning nearly all of them die later of some complication due to their less-than-fully-formed organs. And the ones that make it tend to suffer from severe disabilities.

“These infants have an urgent need for a bridge between the mother’s womb and the outside world,” Flake said in a statement. “If we can develop an extra-uterine system to support growth and organ maturation for only a few weeks, we can dramatically improve outcomes for extremely premature babies.”

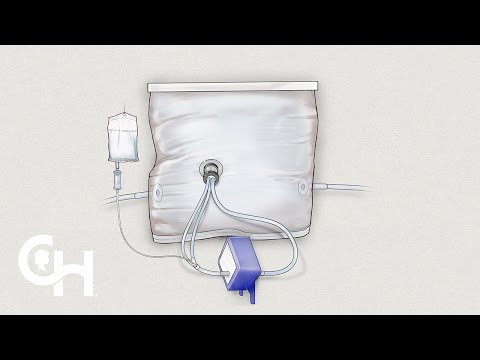

In other words, instead of putting extremely premature babies into incubators and covering them with IVs, ventilators, and monitors, doctors would pop them right into a womb with a view.

What does it do?

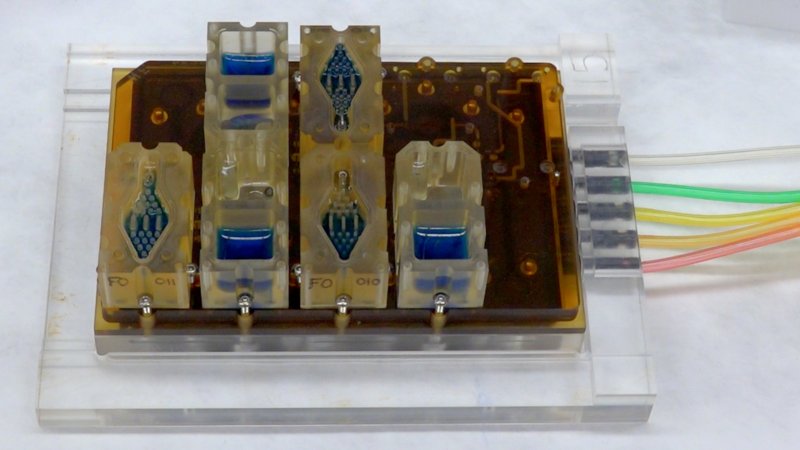

The new study didn’t use human infants, but sheep. Over the course of several years, the researchers developed several prototypes designed to support preterm lambs—of a gestational age equivalent to around 23 to 24 weeks in a human—outside the womb.

Ersatz amniotic fluid keeps the neonate in an environment more friendly to its underdeveloped body, supplying nutrients and growth factors, and the sealed environment keeps them safe from infection. Instead of taxing the fragile lungs and heart of the fetus with pumps that drive blood circulation and ventilators that push air into their lungs, the apparatus keeps the patient tethered to life support via its umbilical cord.

Previously, similar systems had only kept fetuses alive for a matter of days. But the new study reports nearly a month of gestation—and some healthy baby lambs that continued to develop as if they were still inside a womb. Lambs who benefited from that extra month of womb-like surroundings were moved to regular ventilators and seemed to live totally normal lamb lives. At least one has survived a full year.

Here’s what those little lambs looked like inside their biobags:

Can this save human babies?

Experts sure seem to think so. Jay Greenspan, a pediatrician at Thomas Jefferson University who wasn’t involved with the study, told NPR the device was a “technological miracle”. Temple University’s Thomas Shaffer said it as a “major breakthrough.” Those are some serious superlatives for independent comment on a scientific study. The CHOP researchers say they hope to conduct human trials in just a few years.

But while the technology is undoubtedly promising—a rare breakthrough in a world full of scientific “breakthroughs” that don’t live up to the hype—that timeline may be overly optimistic.

“This will require is a lot of additional preclinical research and development and this treatment will not enter the clinic anytime soon,” Colin Duncan, a professor of reproductive medicine and science at the University of Edinburgh (and who wasn’t involved in the new study), said in a statement. “The use of steroid injections for women at risk of delivering a premature baby to help accelerate fetal lung development was discovered using sheep models. It has improved the survival of premature babies worldwide and made a huge impact on obstetric and neonatal practice. That treatment took well over 20 years to get into clinical practice.”

A sheep is not a human: their gestation period is much faster (just 152 days total) and they’re bigger. So the researchers need to scale down the apparatus to support babies that are often born weighing less than a pound, and it’s hard to say whether a human fetus would survive as swimmingly for the 4-5 weeks it would take to carry them past immediate danger. They’re also not sure that the human umbilical cord will cooperate as well as the lambs’ did. Lambs provide a great proof-of-concept—the team won’t be going in blind when they try to adapt the device to support human life—but it’s not like they can use the current design on a human with no changes.

And then there’s the question of just how well this new system will catch on.

“I’ve talked to other practitioners who think that families might not be able to accept that their baby is going to be placed in a bag for four weeks,” Riley Hospital for Children’s Brian Gray told Stat News. “It’s very science fiction-y. Some people might not be able to accept that.”

The CHOP researchers are adamant that they’ll make the device family friendly by the time they reach human trials—it’s not like human babies will be hanging in bags on the walls of neonatal intensive care units—but sealing a baby up in a sack of liquid is definitely not something you expect when you’re expecting.

And even once it works, there are limits to what the apparatus will be able to do. Like we said before, it’s not going to totally replace natural gestation—who knows if or when scientists will be able to improve the device to the point that it can support babies before 22 weeks of gestation. And even those infants will need to be properly prepped: The Atlantic reports that patients will have to be delivered by C-section and given a drug to keep them from gasping in a big breath of air, which can cause irreparable damage to their delicate lungs. And they’ll need to be transferred to the bag and hooked up to their new placenta pretty much immediately.

So this miraculous invention doesn’t come without its hiccups—and whenever it actually makes it to hospitals, it may prove to be a hard sell. But eventually, the new device could indeed save lots of little lives.