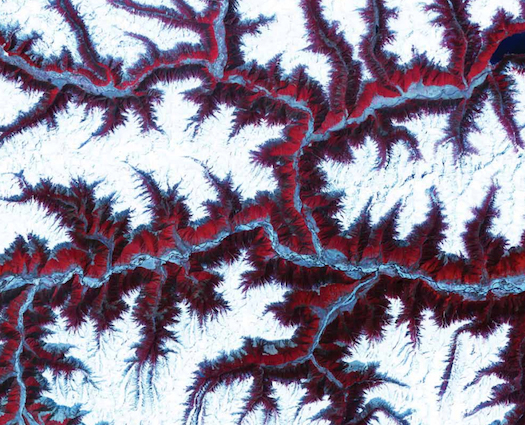

Last Friday, strangely shaped clouds in shades of deep blue and aqua danced over Norway for around half an hour. The alien visuals, set against the more familiar green tinge of the aurora borealis, were not evidence of an extraterrestrial visitor, but rather a sign that a new NASA experiment is underway.

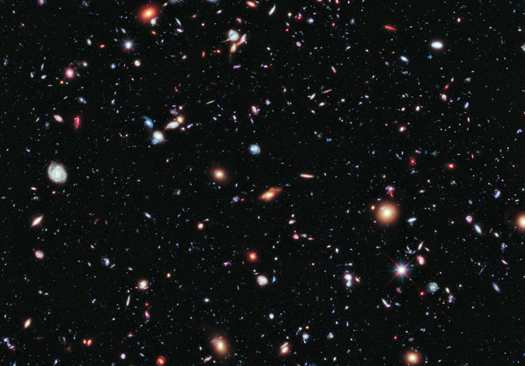

The NASA-funded Auroral Zone Upwelling Rocket Experiment––or AZURE––aims to help scientists better understand how the forces that create the northern lights change our planet’s atmosphere. Specifically, the aurora borealis’ technicolor light show is the result of powerful collisions in which highly energetic particles from the sun—often collectively referred to as solar wind—crash into gases in Earth’s atmosphere. These collisions produce bursts of light, the colors of which are unique to the identity of each gas: oxygen creates the typical yellow-green aurora, whereas nitrogen makes a blue or purplish one.

All of that energy bouncing around up there is slightly concerning. Satellites that enable text messages and GPS navigation hang out in the same realm, so scientists want to know as much as they can about how this sliver of airspace functions, and ensure that access to the tech is never interrupted.

Over the next two years, AZURE and seven other research missions, together known as The Grand Challenge Initiative, will release canisters of gas into Earth’s upper atmosphere, just as the inaugural spacecraft did last week to produce the image above. Similarly to the elements that color fireworks, the gases NASA ejected into the sky radiate hues that make them visible from Earth’s surface. The way the peculiar plumes of these harmless gasses––trimethylaluminum and a mixture of barium and strontium––disperse can tell scientists more about how energy flows in near-Earth space.

The missions will probe the atmosphere near the north pole. It’s here that Earth’s protective magnetic field curves low, where solar wind can penetrate deep enough to facilitate the beautiful collisions that scramble the chemical and energetic make-up of Earth’s atmosphere.

AZURE focuses on the ionosphere, an electrically charged band of atmosphere that sits between 46 and 621 miles above Earth’s surface. By triangulating the movement of the colored gas clouds from the ground, AZURE will help scientists better understand how this energy moves.

![NASA Has Spent $20 Billion On Canceled Projects [Infographic]](https://www.popsci.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/03/18/HGHSRRE2QJXPSET7ZZQOK6YCXE.jpg?w=525)

![How Much Would It Cost To Live On Mars? [Infographic]](https://www.popsci.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/03/18/KVOTBHJ5JNT7DVBTWAGRTRUOE4.jpg?w=525)